Moments in Other Latitudes:

Travel Anecdotes

Soweto, Phuket, and the Value of the Unnecessary

Part 1: South Africa, the Country That Bet on the Improbable

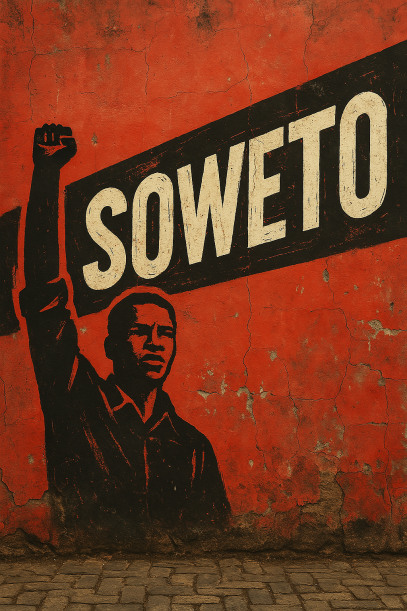

The world looked to South Africa in 1995. After decades of rule by oppression and the crushing of protests, Soweto uprising in 1976 among them, the revolution reached its end without becoming a civil war. Against every forecast, the country began a new stage marked by calm and self-respect. It turned away from both revenge and further violence.

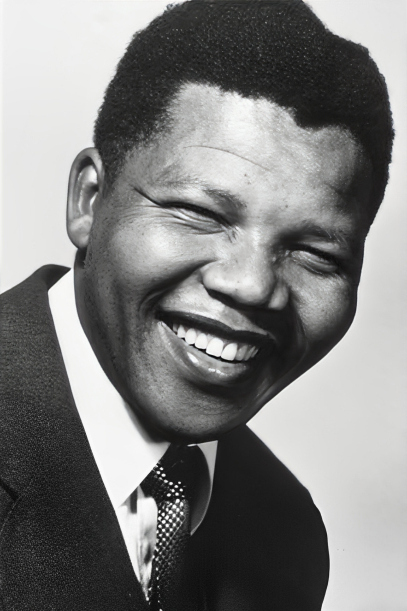

Calm did not descend suddenly on South Africa; its roots went back to the year before. After twenty-seven years in prison, Nelson Mandela faced freedom with a quiet patience as the country prepared for change. That April of 1994, people waited for hours to vote, side by side.

The structure of apartheid, once upheld by law and hatred, was finally gone. People sometimes question the Nobel Foundation’s choices. At the time, the 1993 award to Mandela and de Klerk had a quiet justice to it. It suggested, without saying much, that South Africa was beginning to turn a very old page, in its own slow way.

The story of South Africa’s rebirth didn’t unfold in speeches or parades. It was scattered in the dust of the streets, echoed in the stadiums, whispered through the slow turning of ordinary days. And I can still picture that winter of 1995, far to the south. Back home in Uruguay we were only just discovering the web, tiny steps really. But over in Africa the Springboks were taking leaps. They beat New Zealand and lifted the Rugby World Cup. I remember thinking how odd it felt, close, unreal, as if the world had stopped for a breath and glanced at itself for a second.

For many of us, it was quiet yet certain that history had changed direction. The image that stayed was not a score or a final try. What remained was Mandela himself, calm and smiling, wearing the green jersey of a team whose meaning had transformed. I can still see him handing the cup to François Pienaar, the captain, standing there almost in disbelief. The scene felt unreal, fragile for a moment, and then lighter, as though something old had finally begun again.

(© Jean-Pierre Muller / AFP / Getty Images).

Everywhere I looked, South Africa was in the news. Apartheid had fallen, the Nobel Peace Prize was shared, and the country was learning to vote without fear. They had even won the Rugby World Cup. That was when I decided to go. Johannesburg was considered dangerous, but I wanted to witness what the world was celebrating.

The internet was barely starting, and chess news filled no more than twenty web pages.

I knew no one in this simmering country, which was just beginning to redraw its identity. So I came up with a simple and somewhat naive idea: to email some Mathematics professors at the University of Johannesburg, under the pretext of asking academic questions... while actually seeking travel advice. When I had nearly given up hope, one of them replied. And that timely response sealed my decision.

I still remember that moment. I began the adventure with ticket confirmed, suitcase ready, passport in order. I could not have foreseen its profound depth; one of those journeys where, as is often the case, what truly endures is not the planned itinerary... but the unforeseen turn of events.

Part 2: The Unnecessary Prevention of a Harmless Oversight

The idea of travelling took shape one spring morning in Montevideo in 1995. I visited the South African consulate to ask what documents I would need a few months later. The exchange was short, almost mechanical:

— "Valid passport and yellow fever vaccination certificate."

— "Is the vaccine mandatory?"

—"Yes, to protect you from the virus at your destination."

There was no room for doubt. I set out to find where they administered that exotic vaccine in Montevideo. I ended up at the Military Hospital, where they still kept reserved doses, primarily for Uruguayan soldiers departing on peacekeeping missions in Africa. They injected me with the attenuated virus, and for three days I cursed the fever, the chills, and the absurd idea of wanting to travel so far.

After overcoming the fever and with certificate in hand, I resumed my preparations with the feeling, naive as so often, that I now had everything under control. I packed my bags, organized my documents, had my flight status OK. Everything seemed in order.

But I hadn't accounted for last-minute traps. I realized this when the plane began its descent into Johannesburg. The captain announced the local time, the destination temperature... and reminded us that as this was a flight originating from South America (São Paulo–Johannesburg), it was mandatory to present the yellow fever vaccination certificate. I checked my waist pouch several times. Nothing. The yellow document was missing.

It was a direct flight. Back in 1995, when international rules about layovers were not yet so strict, things were more flexible. Today, just a few hours transit in a yellow fever country would require the certificate, even for Uruguayans. But that year, as I checked my waist pouch during descent, I discovered something worse than bureaucracy: I had traveled confidently... but unprotected.

Panic set in. Would they deport me? Put me in quarantine?

I clenched my teeth and walked toward immigration control. During that long walk, approaching the extensive lines of passengers waiting to stamp their passports, I encountered about five enormous columns whose signs indicated, by continent or region, which countries' citizens needed to have their yellow fever vaccination cards ready.

In the column corresponding to South America, I believe all countries were listed except Uruguay and possibly Chile. The list followed alphabetical order: Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador... ending with V for Venezuela.

Truth be told, I thought, “We’re so insignificant we don’t even make the column.”

—"Passport, please", an officer said to me. His tone was tired rather than unfriendly.

I handed over my passport and held my breath.

The officer stamped it and slid it back to me, just like that. No further questions, not even a mention of the yellow fever vaccine.

I walked into the main hall, half-confused, half-relieved, wondering whether I’d simply been lucky. Moving more slowly now, and more curious than afraid, I returned towards the column. It puzzled me that while others were being stopped for their certificates, I had passed as if nothing had happened.

The doubt kept tugging at me, yet I couldn’t just stop any official; what if one of them said, “And your certificate? You haven’t got one?”

I glanced around for someone approachable. That’s when I noticed her — an older woman in a discreet uniform, calm-faced, patient, the sort of person who had probably answered the same question a hundred times without losing her composure.

I moved closer, almost whispering, as though confessing a secret.

—"Excuse me, why isn’t Uruguay on that list?"

The woman smiled with unexpected warmth, as if she knew exactly what was going through my mind. Her answer was simple, final, and almost motherly:

—"Very simple, young man. I believe Uruguay is the only country in South America without yellow fever."

I walked away quietly, unsure whether to laugh or give thanks. That much-troubled document turned out to be unnecessary. South Africa did not require the certificate because Uruguay posed no risk. Ironically, I had been vaccinated to protect one country that didn’t need it—from another that didn’t require it either.

When calm returned, I began to wander through Johannesburg and, above all, Soweto. That vast township, mostly Black, had become the living symbol of South Africa’s resistance to apartheid.

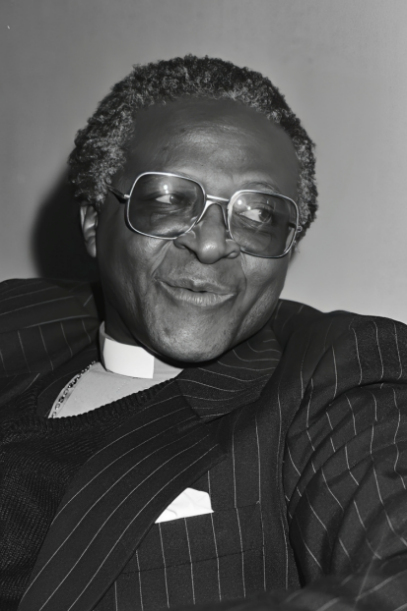

Of all the memories from that journey, Vilakazi Street is the image that still lingers. Two Nobel Peace Prize winners lived there, which no other street can claim.

Desmond Tutu’s 1984 prize marked a quiet bravery in the face of apartheid. Nelson Mandela’s in 1993 marked the labour of stitching a nation back together.

Today their homes are small museums. I went down that street slowly, with a kind of quiet respect, feeling that the place still breathed a story larger than its walls.

Part 3: Thailand: The Immunological Echo of an Old Lesson

About thirty years later, the same pattern appeared again, though in another corner of the world: Phuket Airport, Thailand.

The flight had begun in Istanbul and paused in Singapore before heading southeast. I had almost forgotten the 1995 episode when an officer stopped the man in front of me, also a South American. Without a word he was sent to Health Control.

Moments later it was my turn. I walked up to the officer, who leafed through my Uruguayan passport, his expression still wary:

— "You must also go through Health Control first," he said firmly.

— "Uruguay doesn’t have yellow fever," I replied. "Besides, I’ve just spent two weeks in Europe."

The young officer hesitated and turned to a senior colleague, who barely looked up before giving a curt nod, as though saying, “You should know this.” The stamp fell with a sharp thud, followed by a mumbled “ok, ok,” uttered without even glancing up.

What I found inside a hidden fold of my money belt was not the old 1995 certificate, but the document renewed in 2018 when I was planning another visit to Thailand. I had kept it out of prudence; the yellow fever card was still valid, though its edges bore the marks of time. Back in Montevideo, renewing it, I found not without irony that the paperwork cost as much as a new vaccination. I didn’t need the jab, only the stamp. Yet life has these small absurdities: paying the same for ink as for a needle. Two continents, three decades, and the same story. A nearly useless document… yet unforgettable.

Epilogue: The Value of What’s Missing

Some countries have oil. Others, diamonds. We Uruguayans have something more modest: a sanitary privilege. An epidemiological detail that goes unnoticed, yet at times becomes an unspoken passport.

Doors open for us not just because of the absence of a virus, but also because of that Uruguayan way of being in the world: discreet, hospitable, unconfrontational, and at times surprisingly trustworthy.

In two airports, in two different hemispheres, I witnessed a fact few know and even fewer appreciate: Uruguay has no yellow fever.

The silver lining came from elsewhere. Because while South Africa didn’t require it, other destinations demand the certificate if you’ve transited through a risk country. And there, having it, even if forgotten at the time, became a retroactive blessing. So in the end, it wasn’t so bad to have been vaccinated after all.

Years later the rules changed. The World Health Organization announced the vaccine lasts a lifetime.

In the nineties, the same paper still carried an expiry date of ten years. I remember that line in small print, and how time proved it wrong, as it often does with memories that refuse to fade and end up more vivid than before.

So yes, the certificate was partly useless, yet also a teacher. It showed me that we often carry papers out of fear and later understand them with gratitude. It reminded me that even what we forget can end up protecting us.

Some countries rebuild themselves after tragedy. South Africa did. Others shine through tourism. Thailand manages that. And there are small, quiet countries that surprise us precisely because of what they lack.

That day, in Phuket, I grasped something else: that the certificate itself mattered little, and that what seems useless, if allowed to grow, can turn into courage.