1950

First heartbeats

Future chess players

Twelve ‘Angry’ Babies, in 1950

The world those twelve were born into in 1950 was still holding its breath after the war. It was a world learning to rebuild itself from the ruins. Unaware of it, they inherited the tension of an age that demanded resilience and strength of character from the very cradle.

I chose twelve of the most remarkable; the list could easily have been longer.

The number twelve gathers them: a

sacred figure in Sumerian culture,

an echo of completed cycles, and an inevitable nod to the film

12 Angry Men

.

These twelve, in particular, found their battlefield upon the sixty-four squares of the

chessboard,

where conflict turns into strategy, art, and eloquent silence.

If in the jury room the struggle was for one man’s life, in the tournament hall it was

for the immortality of an idea.

In both cases, conflict is no accident: an indelible mark of the human condition.

1. András Adorján

A Hungarian Grandmaster (a title he earned in 1973) and a writer known for his combative ideas, his proclamation Black is OK!

, and its sequels, was less a manual and more a manifesto for viewing the black pieces with self-assurance. He adopted his mother's surname in 1968. His peak rating reached 2570 in January 1984; that July, he was ranked twentieth in the world. His potential was clear from his youth: he was runner-up in the 1969 World Junior Championship, behind none other than Anatoly Karpov.

Adorján stood out as a consummate competitor and played a decisive role in Hungary’s celebrated Olympic gold triumph in Buenos Aires in 1978. An uncomfortable and provocative thinker in the best sense, he left behind work that I reread as though consulting a lucid dissident. Within my extensive library, many of the books by this brilliant author are located in close proximity to a few of my notebooks, thus serving me as a reminder that chess can also be considered an intellectual pursuit.

He passed away at his home in Budapest on 11 May 2023 after a protracted period of illness. He was seventy-three.

His death did not go unnoticed in the chess community, gone is a competitor with a sharp style, as well as an author whose challenging ideas made people uncomfortable, both at the board and in his writings.

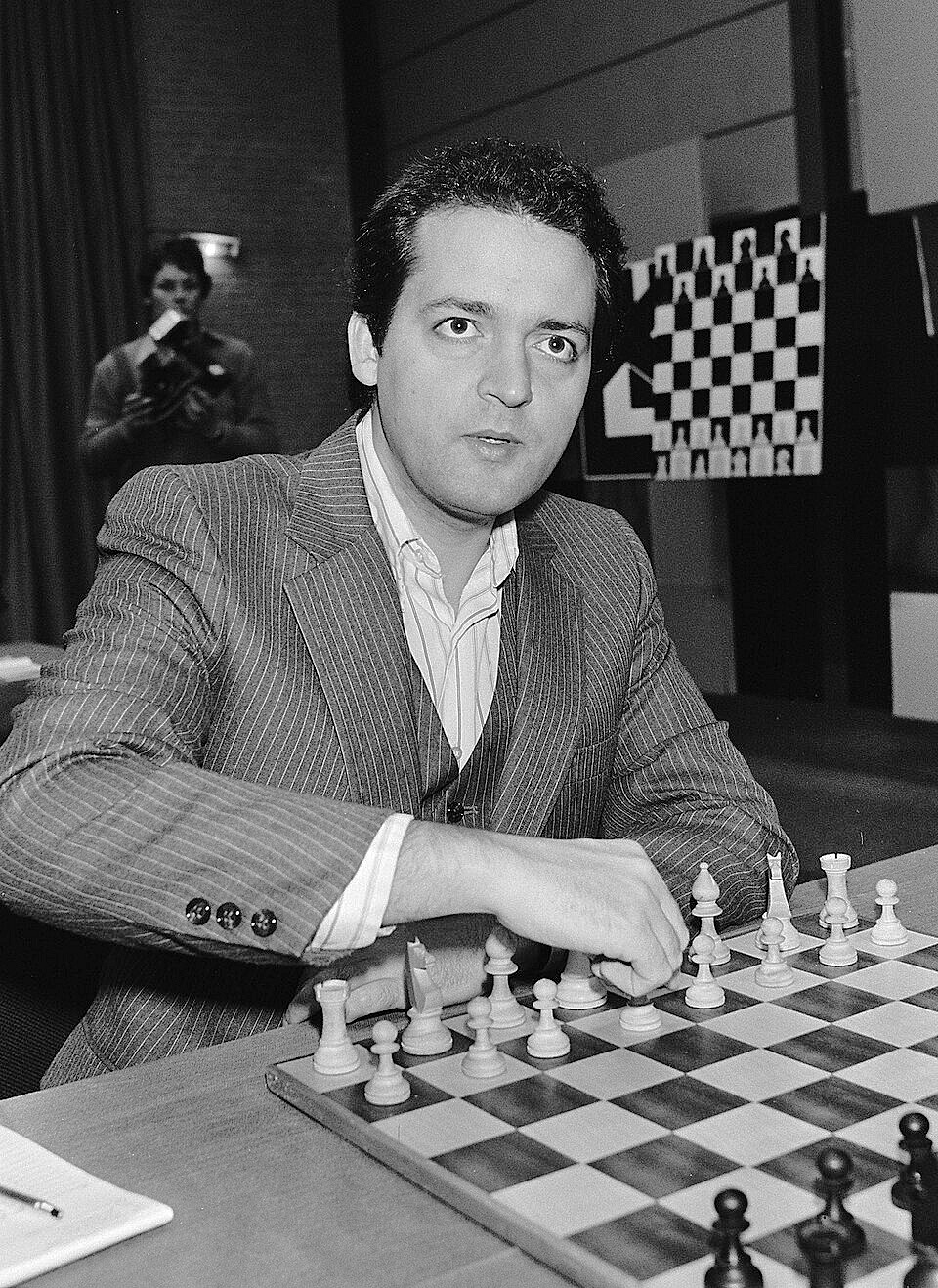

2. Ljubomir Ljubojević

I first ran into Ljubo in Buenos Aires in October ’94, at the Lev Polugaevsky Masters. The magnetism, and that impulsive energy, with which he ruled the analysis room were the very qualities that shone in his games: a will to embrace risk, seize the initiative, and push where others would yield.

That second-last place at Wijk aan Zee in 1972 was a first step, not a stumble. Eleven years later, in FIDE’s January 1983 rating list, he stood shoulder to shoulder with the K–K duo: world No 3 on 2645, behind only Karpov (2710) and Kasparov (2690). Beyond the numbers, what endures is his aesthetic ethic: playing to win as the highest form of respect, towards the audience and towards the game itself, even when the easy path counselled caution.

3. Evgeny Sveshnikov

He gave his name to an idea: the Sicilian with …e5, which many initially viewed with scepticism, became a laboratory of modernity under his care. Sveshnikov was a theorist, a trainer, and a polemicist.

His books on ‘his’ Variation and the c3 Sicilian are among the most heavily underlined on my shelf; not out of fetishism, but because they taught me how to connect principle and practice. When a student finally understands why 5…e5 changes the entire landscape of the middlegame, that is when Sveshnikov’s spirit appears: the pedagogue who turned doubts into paths.

4. Sam Palatnik

Palatnik’s migration from Odesa to the United States brought with it a method. A Grandmaster since 1978, he was a reliable player; as a coach and author, his impact was greater still. His belief that chess is a model for life becomes practical in books co-written with Lev Alburt: in Chess Tactics for the Tournament Player, tactics become a language, and the eye is sharpened diagram by diagram. I use it in my own courses with excellent results.

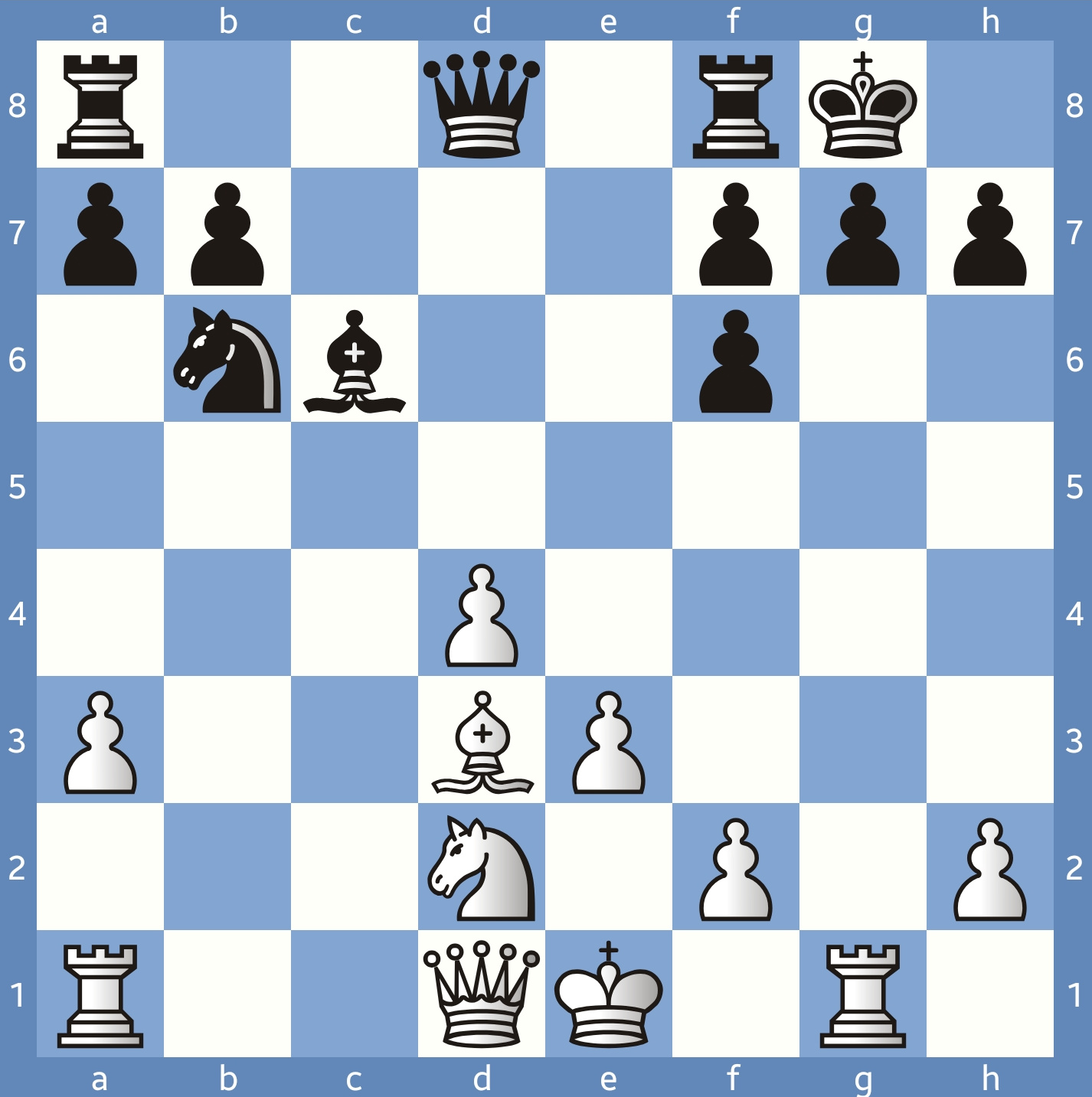

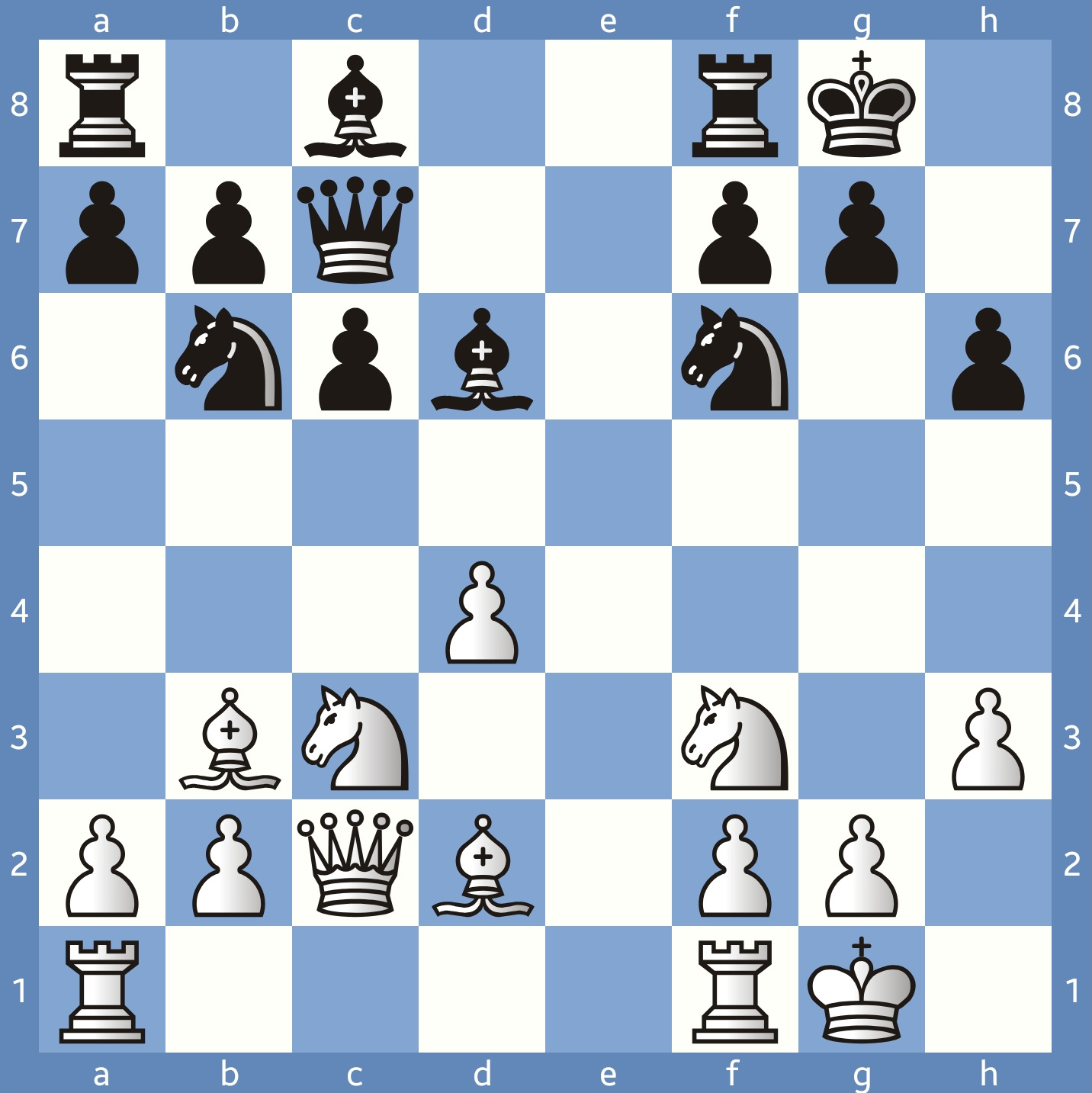

Semon Palatnik (2500) — Efim Geller (2550) [D00]

USSR Team Cup, 11th, Rostov-on-Don (2), 05.1980

1.d4 Nf6 2.Bg5 d5 3.Bxf6 exf6 4.e3 Be6 5.Nd2 Nbd7 6.c4 Bb4N [6...dxc4 Trompowsky — Van Scheltinga, Buenos Aires ol (Men) fin-A 1939 (10) ½-½] 7.cxd5 Bxd5 8.Nc3 Nf8 9.Nge2 0-0 10.Nb3 Nb6 11.a3 Bxc3+ 12.bxc3 c5 13.Bd3 cxd4 14.cxd4 Bxg2?? 15.Rg1 Bc6

15.Rxg7+!! [1-0]

Since 1994, he has developed his work in the United States: Honoured Coach of Ukraine, mentor to numerous grandmasters, official coach for the USCF in World School Championships, and also for the national Olympic team. In Maryland, he leads the UMBC team as Associate Director and coordinates the Mid-Atlantic region for the Kasparov Chess Foundation. His legacy is twofold: results, and a method that teaches how to see.

5. Konstantin Lerner

Konstantin came into the world in Odesa and twice lifted the title of Ukrainian champion, in 1978 and again in 1982. Two years after that, in Lviv, he stood just behind Andrei Sokolov in the Soviet Championship. Lerner’s style had no need of fireworks: he pressed with patience, exchanged when it mattered, and added weight to every move until the opposing position could barely breathe. In the seventies and eighties he was among those quiet professionals who upheld the formidable standard of the Soviet school.

As Yochanan Afek remembers, once in Israel he turned his attention to the younger generation, guiding future champions. His trademark was clarity: positions stripped of clutter, small advantages patiently nursed. He wore the shirts of clubs like Kfar-Saba and carried an ethic as simple as it was demanding, seek not gratuitous brilliance, but light and order on the board.

In 2001 he resettled in Israel with his family and kept playing in open tournaments. Ten years on, his journey ended in Herzliya, at sixty-one.

6. Valeri Beim

Beim interests me as a craftsman: a player, coach and writer who distils experience into tools.

On my shelves I keep most of his books, a toolbox I return to often.

How to Play Dynamic Chess

explores the initiative;

How to Calculate Chess Tactics

organises combinational vision;

Lessons in Chess Strategy

and

Back to Basics: Strategy

restore principles that never go out of date;

The Enigma of Chess Intuition

dares to touch what we cannot always name;

Understanding the Leningrad Dutch

grounds plans in structure;

Chess Recipes from the Grandmaster’s Kitchen

reads like a workshop notebook; and

Paul Morphy: A Modern Perspective

teaches us to read the past through today’s eyes.

This is not literature of shining phrases; it is fine ironwork for practice.

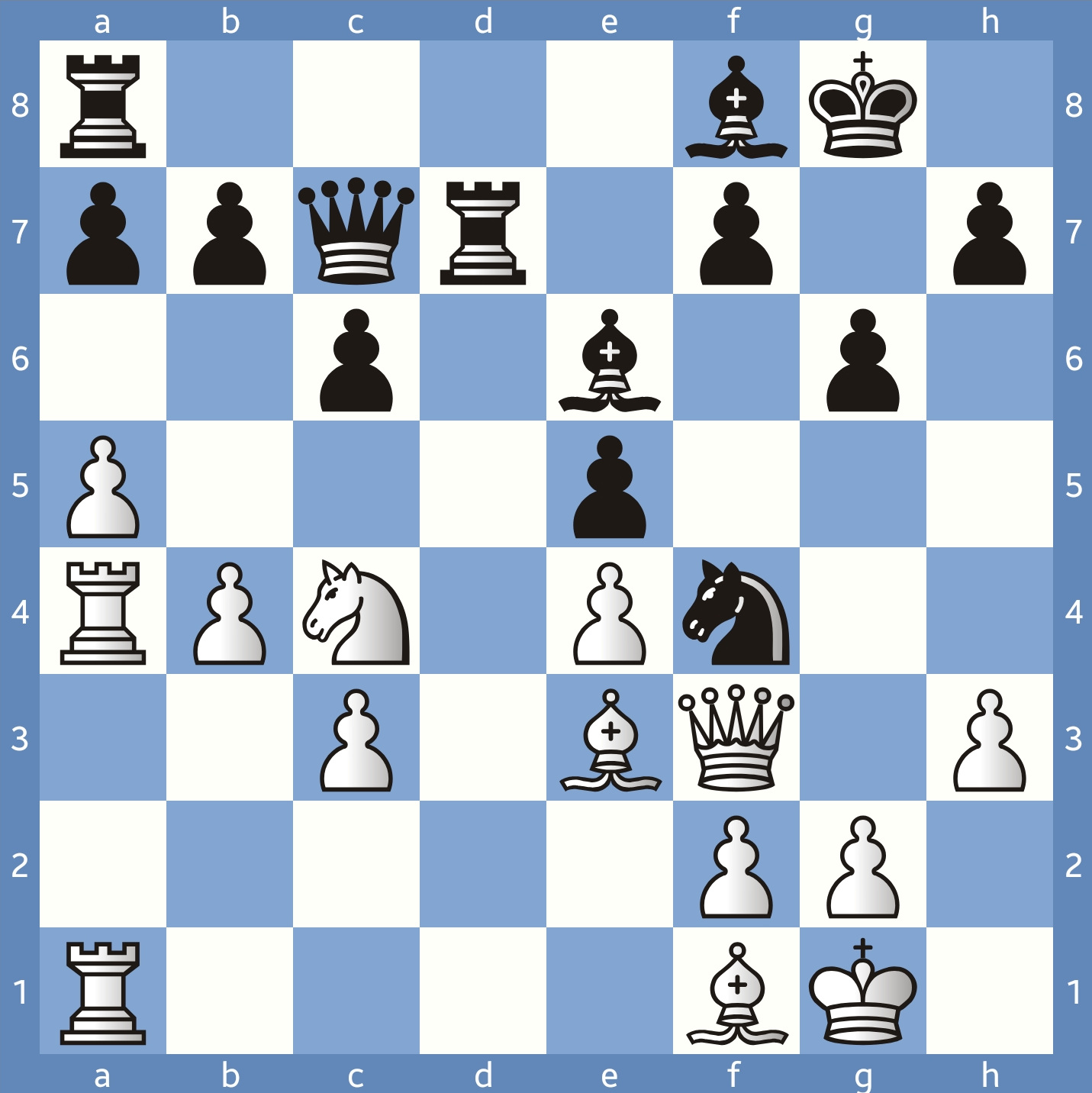

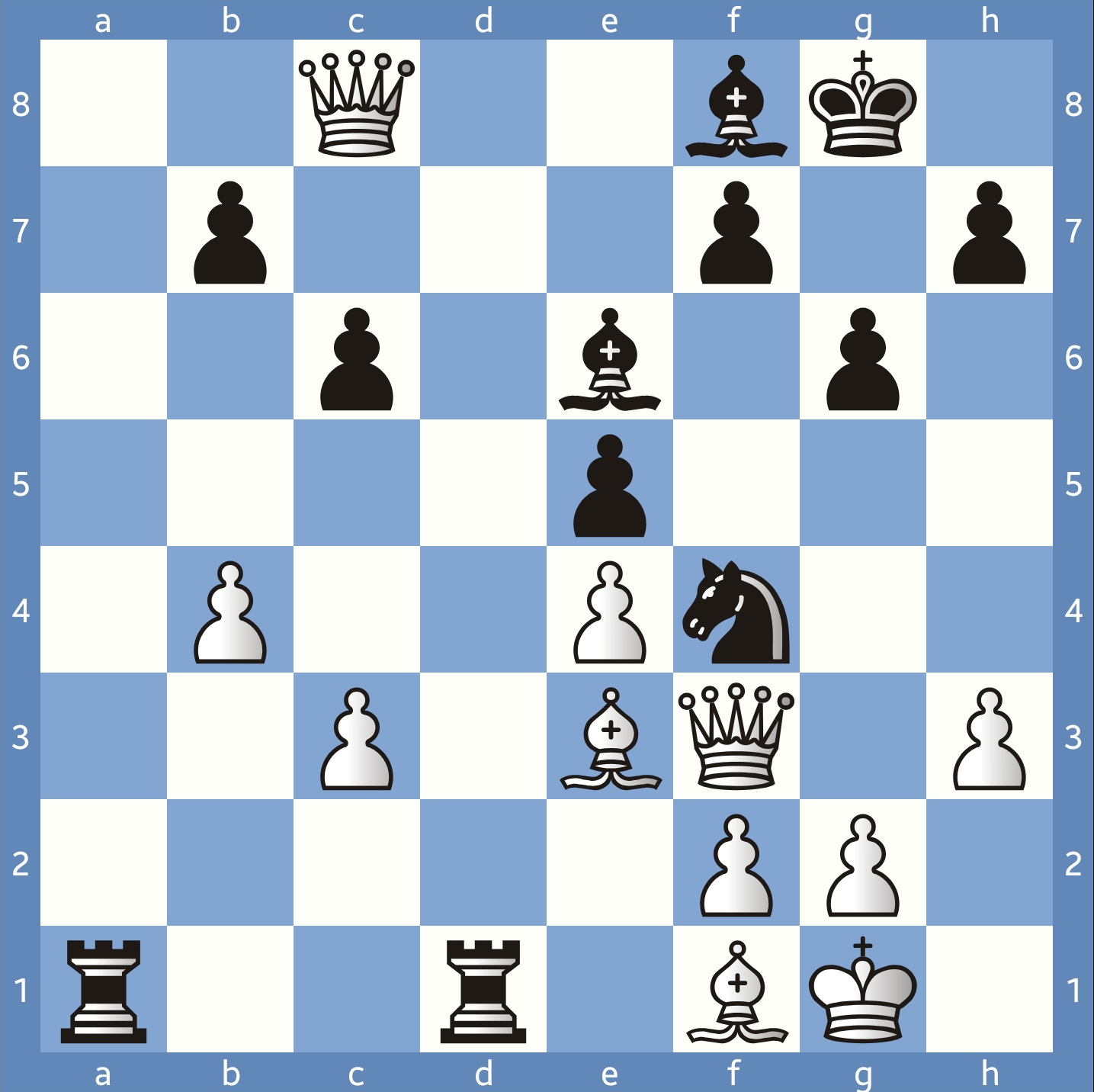

Marco Thinius (2300) — Valeri Beim (2500) [B08]

Berliner Sommer 11th, Berlin 1993

One of the most striking games of the eleventh Berliner Sommer in 1993, held at the Sports and Congress Centre of Hohenschönhausen, was the encounter between Marco Thinius and Valeri Beim in the opening round. After 21 moves the following fascinating position appeared on the board:

Berliner Sommer 11th(Berlin, 1993), after Black’s 21st move.

White enjoyed more space and freedom of action, a position that looked advantageous. Had Beim miscalculated and overlooked the fork after Nb6? Or had he, rather, set a trap? Personally, I cannot tell. What is certain is that young Thinius did not hesitate to play what almost everyone in the room suspected. The game continued:

22.Nb6? [22.g3!] 22...axb6 23.axb6 Rxa4 24.bxc7 Ra1 25.c8=Q Rdd1

We arrive at an extraordinary position, one seldom seen over the board: two white queens without a rook; Black pressing fiercely on the back rank with a battery of rooks, and no queen at his side.

“Who is better?” I asked myself; the very question that must have occurred to the spectators in the playing hall. The honest answer: I do not know who is worse. At such times the wisest response is the one found in old manuals: simply “unclear” or, as some put it, infinity.

Marco Thinius, who, as I later discovered, is also principal bassoonist with the Staatskapelle Weimar, chose to retreat the queen on c8, trusting he could withstand the storm gathering around his king. But there lay a surprise. To survive, he needed 26.Qxd1!!, though how to see it when one already feels victorious?

The game went on:

26.Qb8?? Rxf1+ 27.Kh2 Rh1+ 28.Kg3

Since these cultural notes aim at something different, and to add suspense, I will not give the final moves. Let me suggest instead that the reader discover for themselves how Beim contrived to escape with the full point and return to his hotel in triumph. See the account here.

7. Slim Bouaziz

A pioneer of Arab and African chess, he broke ground as the first grandmaster of Tunisia and of the entire continent (1993).

He played in five Interzonals. I confess I did not know his career in detail.

What I do remember, from childhood, is that Bouaziz (then just 17) finished last at the

Sousse Interzonal 1967,

scoring a few valuable draws and a single win against GM

Robert Byrne.

Was he the youngest in the event? Almost: Mequinho

also played, aged only fifteen.

That Interzonal remains memorable for several reasons. One recalls the tempestuous Bobby Fischer walking out of the competition at the height of his powers. The immediate cause was a dispute with the organisers over the schedule: as a practising Jew, he refused to play during the Shabbat. Although an initial agreement was reached, his game against Efim Geller was fixed for a Friday afternoon. Fischer did not appear, lost by forfeit, and felt it was a betrayal he could not forgive.

Despite his demolition job in the earlier rounds, and even though the organisers later yielded to his demands, Fischer’s fury had no brakes. The damage was done. He felt his integrity had been violated and, in a gesture of defiance, he abandoned the tournament and left Tunisia.

Years later, Bouaziz’s name echoed again in my memory for a particular reason: the Dubai Olympiad 1986.

There, Bernardo Roselli,

multiple Uruguayan champion whom I had met as a boy at a tournament in

Carmelo, his hometown, defeated him in a fine game.

The celebrated publication Šahovski Informator

later annotated it in its volume 42.

And since we are on Olympiads, let us revisit a miniature by Slim from the Siegen Olympiad 1970, against the Peruvian player Orestes Rodríguez Vargas.

Slim Bouaziz — Orestes Rodríguez Vargas [C88]

Olympiad-19 Preliminaries A, Siegen (5), 09.09.1970

1.e4 e5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.Bb5 a6 4.Ba4 Nf6 5.O-O Be7 6.Re1 b5 7.Bb3 O-O 8.h3 Bb7 9.c3 d5 10.exd5 Nxd5 11.d4 exd4 12.cxd4 Af6 13.Nc3 Nxc3 14.bxc3 b4 15.Ab2 Qd6 16.Qd3 bxc3 17.Bxc3 Rad8 18.Rad1

The man with the black pieces was Peru’s national champion, a title he held five times in succession (1968–1972). Although it may not seem obvious at first sight, White’s position was more comfortable; Black could find no clear plan against a rival who handled the isolated queen’s pawn with precision. As often happens in these structures, Black rushed with a nervous move:

18...Nb4?? (better was 18...Ne7)

Bouaziz immediately spotted the slip and gave up the bishop pair without hesitation, for a powerful reason:

19.Bxb4! Qxb4 20.Bc2 [1–0]

A short, almost textbook game, yet enough to remind us that Bouaziz had a tactical edge ready to seize upon the smallest error.

8. Vladimir Okhotnik

Okhotnik embodies maturity without haste. Ukrainian champion in 1979, he later settled in France and crowned his path with the World Senior Championship in 2011 (and again the 65+ title in 2015). As an author, together with Bogdan Lalić he produced two widely read volumes: Carpathian Warrior. Book One: Secrets of a Master and Carpathian Warrior 2, devoted to the Pirc, the Modern, the Czech, the Philidor and other black fianchetto systems. What I like is his quiet invitation: to play Black without complexes, with patient manoeuvre and counter-attack in due time.

In his most personal work, It is Never Too Late to Become a Grandmaster (2021), he adopts an autobiographical tone that goes beyond the board. “For a veteran, chess remains a vast space of self-expression,” he writes, mindful of the challenges his generation faced with engines and computer preparation. After six decades in the game, his conclusion is simple: chess is not confined to science, art or sport; it is part of living. From Uzhhorod, in western Ukraine, he still enters tournaments and passes on his way of seeing, steady under pressure.

9. Juan Manuel Bellón López

There is constancy in Juan Manuel Bellón’s path: five national titles in Spain, the grandmaster title since 1978, and a presence in Olympiads and international arenas where his combative style became his signature.

For years now he has lived in Stockholm (Sweden), sharing both life and board with Pia Cramling, grandmaster and inseparable partner: together they embody one of the most emblematic couples in contemporary chess.

I met him in Buenos Aires, in April 1994, during the “12 Banderas” tournament: approachable, warm, one of those grandmasters who converse naturally, as if no distance existed between board and spectator. That same quality of openness runs through his career: a player of high competitive level and, at the same time, a human reference point who moves through chess as if it were his own home.

10. Peter Biyiasas

Biyiasas simboliza el esfuerzo de un ajedrez periférico que se hace un lugar. Doble campeón canadiense y olímpico habitual, disputó torneos fuertes en Europa antes de radicarse en California. Su estilo fue práctico, terso, con la virtud de tomar decisiones claras en posiciones con ruido. En la historia del ajedrez norteamericano de los setenta, su nombre es una bisagra: ayudó a que Canadá dejara de ser un invitado tímido.

11. Péter Lukács

He made his career quietly, without chasing the limelight. Lukács, Hungarian champion in 1980 and active for years in leagues and team events, belongs to that essential category: sustaining the internal level that makes a school’s excellence possible. When I revisit his games, I find respect for technique and a healthy resistance to dogma. His relevance as a “1950 birth” is to remind us that chess is also built from local constancy.

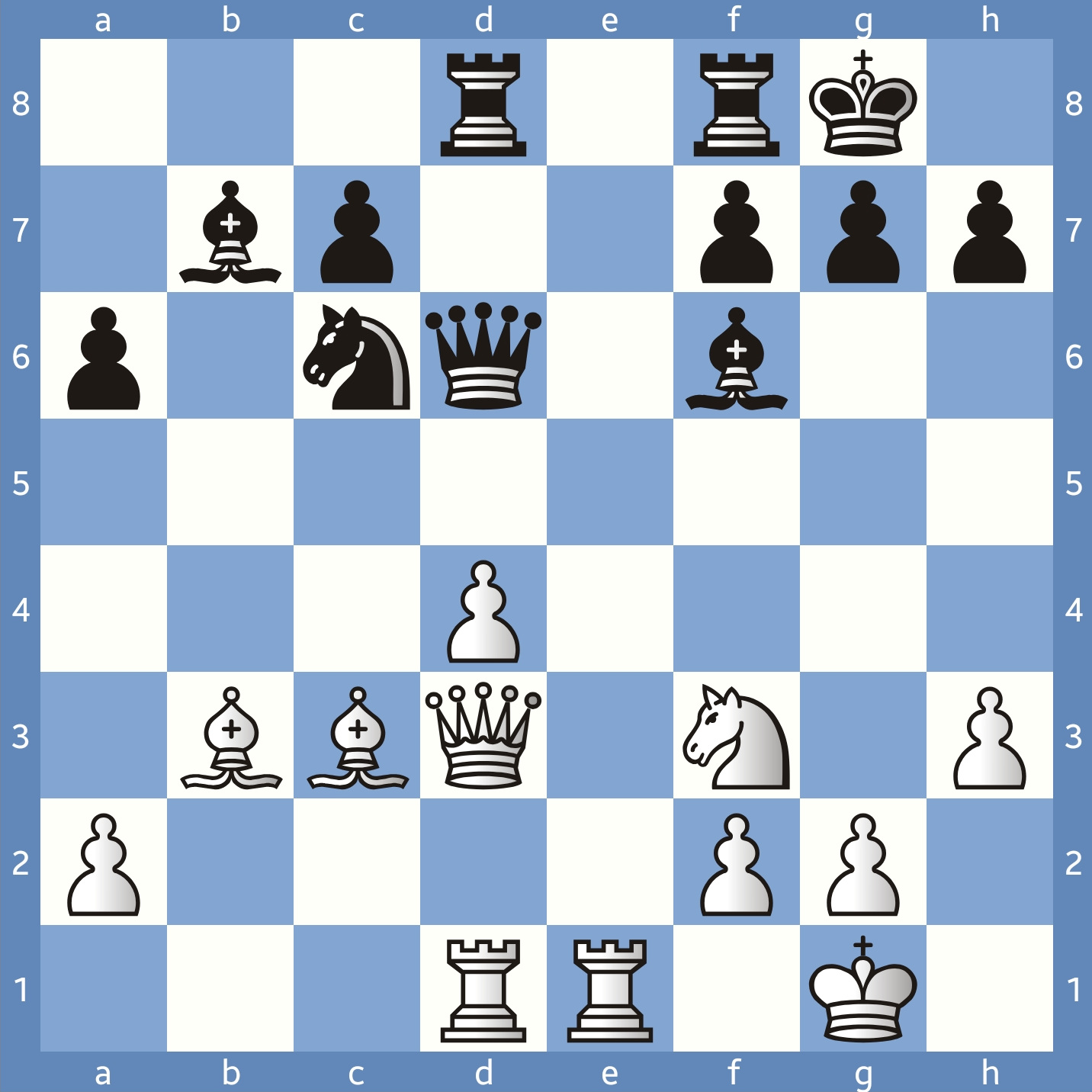

Péter Lukács (2475) — László Bárczay (2420) [D46]

Budapest, 09.08.1998

1.d4 d5 2.c4 e6 3.Nf3 Nf6 4.Nc3 c6 5.e3 Nbd7 6.Qc2 Bd6 7.Bd3 dxc4 8.Bxc4 O-O 9.O-O e5 10.h3 Qc7 11.Bd2 exd4 12.exd4 Nb6 13.Bb3 h6??

14.Bxh6!! gxh6 15.Qg6+ Kh8 16.Qxf6+ [1-0]

12. Julio Kaplan

I cannot think of Julio Kaplan without recalling Jerusalem in August 1967, just weeks after the Six-Day War. The World Junior Championship was held in that tense post-war atmosphere; there were doubts and absences, yet twenty countries eventually lined up (I can confirm it from the tournament bulletin I keep).

What made it unusual was that two Argentines were in the field: Víctor Brond (as the official representative, though he did not play in the final) and Kaplan, Argentine by birth and national champion of Puerto Rico. In that stark setting Kaplan won Final A and was awarded the title of International Master by FIDE.

Julio Argentino Kaplan Pera was born on 25 July 1950 in Buenos Aires, Argentina. He moved with his family to Puerto Rico in 1964, and three years later settled in the United States, where he still lives and works for Autodesk.

His victory opened horizons for Caribbean and River Plate chess. Each time I leaf through the chronicles of that tournament, I feel again the mix of uncertainty and lucidity of a time that forced one to grow up quickly.

Epilogue: the invisible thread

Seen together, these players born in 1950 tell us more than their score tables. There are migrations that rewrote lives (Odesa towards the United States or Austria; Ukraine towards Israel or France), there are books that reshaped ways of thinking (Black is OK!

, the manuals of Sveshnikov, the teaching of Palatnik and Beim, the Carpathian Warrior

series), there are personal encounters that anchor memory (Ljubo and Bellón in Buenos Aires; our countryman Roselli defeating Bouaziz in Dubai 1986), and there is a World Junior Championship played in a city still fresh from war.

As a teacher and trainer, I often tell my students that chess is not learned only through variations: it is also learned through stories that gaze back at us. This dozen of 1950 is part of my bookshelf and of my biography; that is why I celebrate them.

Farewells (Chessplayers)

Sady Loynaz Páez

In our review of those who left us in 1950, the Venezuelan champion Sady (Zadí José) Loynaz Páez-Pumar deserves a place of his own.

He was not an international star, yet he left a deep mark at home. Born in Caracas on 28 December 1909, he became Venezuela’s first national champion in 1938 and later defended the title in matches against Manuel Acosta Silva, José León García Díaz, Omar Benítez and Héctor Estévez. His name belongs to the years when Venezuelan chess was finding its feet and the national federation was taking shape.

In 1939, while Alexander Alekhine was touring South America before Buenos Aires, Loynaz sat among the boards in his Caracas simuls. A short crossing of paths that still mattered.

He abandoned us on 26 September 1950, when he was forty, aged just forty, from a sudden heart attack. The loss touched the Venezuelan chess community deeply.

In the following year he was remembered through the Bolivarian Tournament in Caracas, a simple and heartfelt tribute from friends and fellow players.

Under normal circumstances this note would be brief. Reliable material is scarce, and small mistakes have been repeated for years, including a birth year of 1910 and the loss of part of his family name. For that reason we offer a fuller sketch than usual. It restores his place in the record as a national champion who helped to give shape to Venezuelan chess in the years before Dubrovnik 1950.