1950

First Heartbeats

Future Musicians

Twelve Babies in Harmony, in 1950

The twelve who came into the world in 1950 were born to a planet still catching its breath after the war, a planet learning to sing again amid ruins. Without knowing it, they inherited the urgency of an age that demanded new voices, new rhythms, and the courage to carry them.

I chose twelve of the finest; the list could easily have been longer. The number twelve gathers them here: like the twelve semitones that span the full scale, a cycle complete, a return transformed. These twelve, in particular, found their stage in music: where harmony and pulse contend with the word, where sound becomes both confession and celebration. If their battlefield was rock, and its many tributaries, their prize was not a crown but something more enduring: songs that, when they play, carry us back whole to an era.

1. Stevie Wonder: The Ear As a Beacon

First beats (1950–1960)

13 May 1950. Europe thrilled to the first Formula 1 race at Silverstone. Asia held its breath before the Korean War. And in Saginaw, Michigan, a premature baby named Steveland Morris was born. A complication in the incubator deprived him of sight, but not of music: from the cradle he listened to life with other eyes.

At the beginning of the decade, in the north, the United States was giving birth to voices as different as Ann Wilson and Stevie Wonder, while in the south, Argentina welcomed Luis Alberto Spinetta, a future landmark of Spanish-language rock. Across the Atlantic, Europe, still marked by post-war scars, would see the rise of voices and leaders in emblematic bands such as ABBA, Genesis, Smokie and Supertramp.

Naturally, with these mentions we do not exhaust all the possibilities, but they are names that any music-savvy reader would readily recognise, and they allow us to glimpse how, even at the opening of this decade, the musical future was already beginning to take shape. Among them, let us begin our journey by highlighting Stevie’s story.

His childhood was tough. At the age of five his parents separated and his mother moved with six children to Detroit. Amid poverty and prayers, young Stevie discovered his first school: the church choir. Soon he added street bands, imitations of R&B, and, thanks to a charity, a drum kit that opened the door to other instruments.

At eleven he auditioned for Motown. He dazzled. “Little Stevie Wonder” was born.

Baptism of fire (the 1960s)

In 1963, barely thirteen, he hit number one with

Fingertips

, a live jam that made him a sensation across the country.

Soon after,

The 12 Year Old Genius

sealed the proof: a boy hardly tall enough for the mic was already stirring arenas.

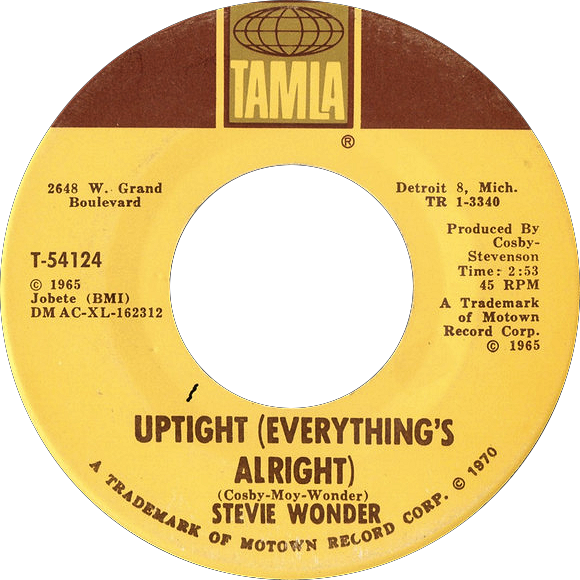

His voice changed, but not his power. Under producer

Clarence Paul,

he delivered songs that defined an era:

Uptight

,

For Once in My Life

,

My Cherie Amour

.

He was no longer “Little”: he had found his own voice.

The sixties were his accelerated apprenticeship: tours, improvised studios on buses, and early fame. The best, however, was yet to come.

The Revolution (the Seventies)

The 1970s confirmed Stevie Wonder as nothing short of a genius. At the start of the decade, he married Syreeta Wright, a union brief in personal terms yet fertile in music. That same year he stood up to Motown and demanded full control of his work. He won, and from then on he was master of his own sound.

Behind the anecdote lay an outpouring of imagination that few artists could rival.

In 1972 he released Talking Book

,

propelled by the jagged pulse of Superstition

.

Its origins can be traced to a chance spark with Jeff Beck.

In the early seventies the distinguished guitarist was searching for a new direction after the break-up of The Jeff Beck Group.

An admirer of Stevie Wonder, he eagerly joined the Talking Book sessions.

The deal was simple: Beck would contribute his guitar to Stevie’s record, and in return Wonder would give him a song for his new trio, Beck, Bogert & Appice.

One afternoon Beck began a drum pattern; Wonder urged him not to stop, and out of that pulse Superstition

was born almost instantly.

Although Beck’s trio recorded their version first, Motown sensed the makings of a huge hit and rushed Wonder’s cut out as the lead single in October 1972.

Stevie had suggested You Are the Sunshine of My Life

as the opener, but the label was adamant: “No, no, no, no, the first one has to be Superstition

.”

To soften the disappointment, Wonder gave Beck another composition, Cause We’ve Ended as Lovers

, which in time became one of the guitarist’s most celebrated performances.

Talking Book

’s success cleared the ground for Innervisions

released a year later, where Wonder confronted America’s racial and political tensions with rare clarity.

In 1973 a serious car crash left him unconscious for days. He came round after a friend sang Higher Ground

at his bedside, as if the music itself had called him back with renewed purpose.

Awards followed in a cascade: in just five years he amassed more than ten Grammys and, unprecedentedly,

won Album of the Year three times (1974, 1975 and 1977), a treble in four editions unmatched by any other artist.

Each record stood as an artistic manifesto.

Even his detour, Journey Through the Secret Life of Plants

(1979), made it clear he favoured exploration over formula.

The World’s Heritage (the 1980s)

The innovations of the seventies gave way, in the new decade, to global reach.

With Hotter Than July

(1980) he folded reggae into his palette and tied his music to a political cause: the struggle to make

Martin Luther King Jr.’s Day a national day of remembrance.

The album became both soundtrack and banner for the campaign.

In 1984, I Just Called to Say I Love You

won an Oscar and lodged itself in collective memory. Let’s be honest: if someone lived through that time and does not remember it, they either have a very poor memory… or they spent those years in some pastoral corner far removed from civilisation.

Along the way came collaborations that made history: Ebony and Ivory

with

Paul McCartney in 1982, and three years later That’s What Friends Are For

, songs of solidarity that circled the globe.

Not long after, he gathered past triumphs into Original Musiquarium I

(1982), while also venturing into the electronic sheen of Part-Time Lover

(1985). That single made chart history, topping four different Billboard

lists at once, proof that his gift could shine as brightly on the dance floor as in pop, soul, or adult contemporary.

The decade closed with his place secured: in 1989 he entered the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, no longer just an artist but a figure woven into the world’s collective memory.

A respected master (the 1990s)

In the nineties, he slowed the pace but not the significance of his work. He scored Jungle Fever

(1991) for

Spike Lee and released Conversation Peace

(1995), with the ballad For Your Love

, which brought him Grammy awards even if not stellar sales.

There were duets with Luciano Pavarotti,

a contribution to Disney’s Mulan

with 98 Degrees,

and the worldwide Natural Wonder

tour,

performed with the sweep of a symphony orchestra.

Motown reinforced his legacy with anthologies such as At the Close of a Century

. Stevie was now less the explosive innovator and more the venerated master, active in humanitarian causes and spiritually tied to Ghana.

A time of testament (2000–2010)

With the new millennium, Stevie’s life was marked by painful losses: Syreeta Wright, his first wife and musical partner in gems such as Signed, Sealed, Delivered I’m Yours

; his brother Larry, and dear colleagues like Ray Charles. Each absence was turned into memory and tribute. 2005 saw the release of A Time to Love

, a gentle album enriched by Alicia Keys and Prince, its songs sounding like chapters of a musical will.

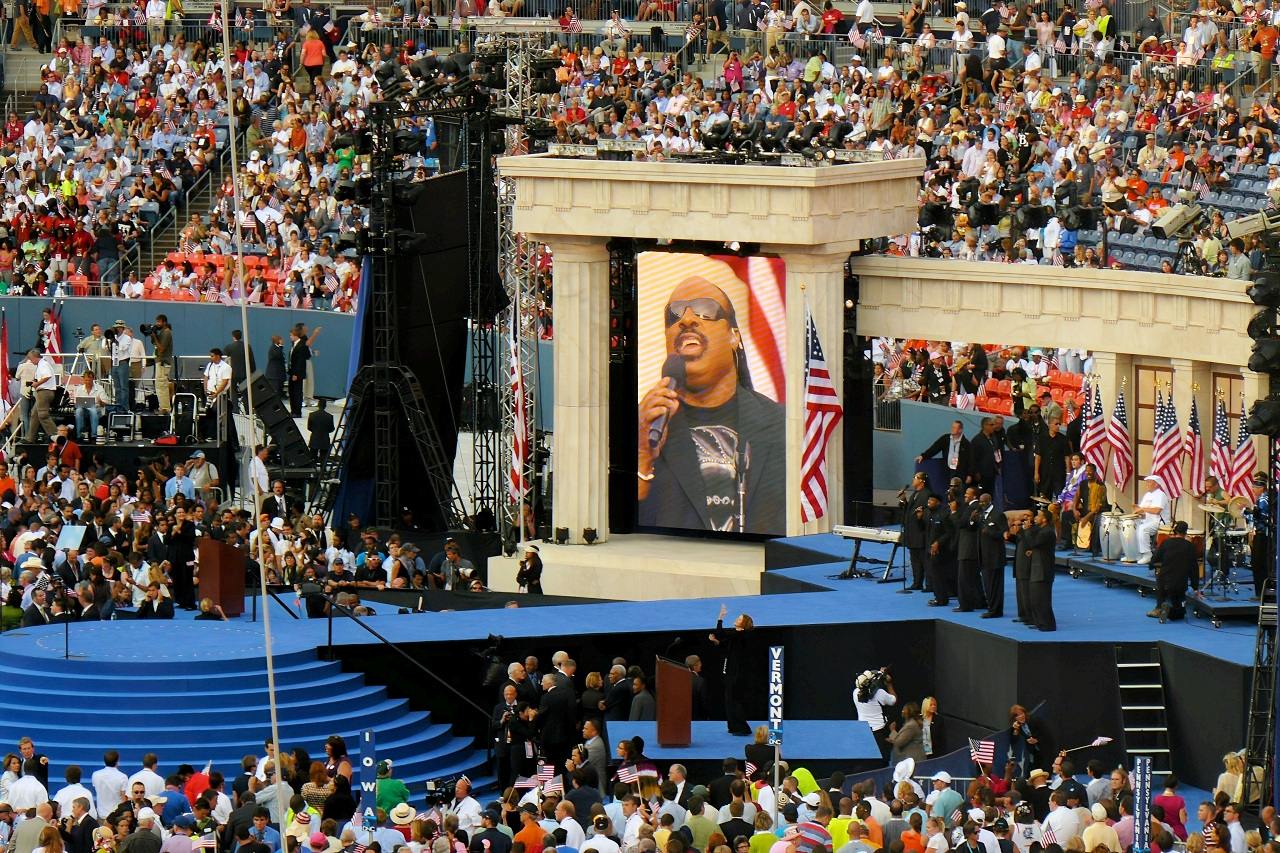

The Library of Congress put the LP Songs in the Key of Life

on the official historic register, which is no small honour. Then in 2009, Stevie was given the Gershwin Prize, and not long after that, the United Nations made him a Messenger of Peace. He wasn't just a brilliant musician anymore; he'd become a proper moral voice.

Resilience and hope (2010–today)

During the last decade, his presence on stage was received as a celebration, marked by tributes including the Billboard Icon Award. His personal life also unfolded in new ways, with marriages and children, though family remained the steady refuge.

In 2019 he disclosed he was to have a kidney transplant. He did so matter-of-factly, and after the procedure returned in restored health.

The pandemic of 2020 kept him away from the stage, though not in silence: he released two songs on his own label, So What the Fuss Music, reaffirming his independence. In 2021 he presented new material at Global Citizen Live.

Rumours persist: Through the Eyes of Wonder

, an album about how the world is perceived by someone who has never seen it, and The Gospel Inspired by Lula

, a tribute to his mother. Still without a release date, they keep anticipation alive.

Epílogue

Today, in his seventies, Stevie Wonder does not sing to fill radio waves. Each song is a political, spiritual or intimate gesture. He is not remembered only for dozens of Grammys or millions of records sold, but for having made of hearing a beacon, and of sound, a way to bring light.

2. Peter Gabriel and the Foundations of Genesis

At the dawn of the second half of the twentieth century, the voice that would give Genesis its theatrical, visionary pulse was born. According to the Chinese calendar, Peter Gabriel (13 February 1950) belongs to the Earth Ox: patience, effort, and an iron gaze.

Alongside him, 1950 also saw the birth of two quiet pillars of the band: Tony Banks (27 March) and Mike Rutherford (2 October). With Hammond organ, Mellotron, and synthesizers, Banks raised atmospheres like cathedrals; Rutherford laid the foundations with bass and clean-cut guitars.

Gabriel turned songs into worlds (myth, dream and social critique) in

Supper’s Ready

and, above all, in

The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway

(1974),

Rael’s odyssey. His aesthetic will stretched Genesis into a true artistic laboratory of the seventies.

On stage he pushed imagination to the limit: costumes, characters, theatricality. Music was not only sound; it was an experience.

To be continued in 1951: the arrival of Phil Collins and the turn toward a more mainstream sound.

3. Spinetta: More Poet than Musician

They named him Luis Alberto Spinetta. He was born in Buenos Aires on 23 January 1950, a child with curious eyes and a listening soul: destined, though no one knew it, to weave words, images and guitars into poetry.

At nineteen, El Flaco

, as he was affectionately known, sculpted a cascade of startling, visionary metaphors:

Muchacha (ojos de papel)

.

More than a song, it was a musical letter to a girlfriend. A simple ballad transformed into a poem of eternal love. Youth with the depth of a sage.

Those who lived the era recall its lyrics as if they were an intimate anthem.

He never stopped. He was a creator of sound worlds: Almendra, the foundational stone of Argentine rock with a poetic soul; then the lyrical and electric fury of Pescado Rabioso; afterwards the oneiric sophistication of Invisible; later, the jazzy colours of Spinetta Jade.

InvisibleHe sang in a tone that might slip close to a whisper and then rise to cut straight through the heart. His words carried images of angels, butterflies and distant oceans, always hinting at some spiritual search.

Rock in Spanish found in him its great poet: a new language, born of wonder and introspection.

He lived for music, he breathed art. He left songs that are seeds, germinating in each new generation. His legacy keeps alive a current of strength and inspiration.

He died on 8 February 2012, yet his presence endures: whenever a guitar turns to poetry or a voice dares to sing the soul’s mysteries, Spinetta is there, the first stone, the quiet murmur, the echo that still shapes rock in Spanish.

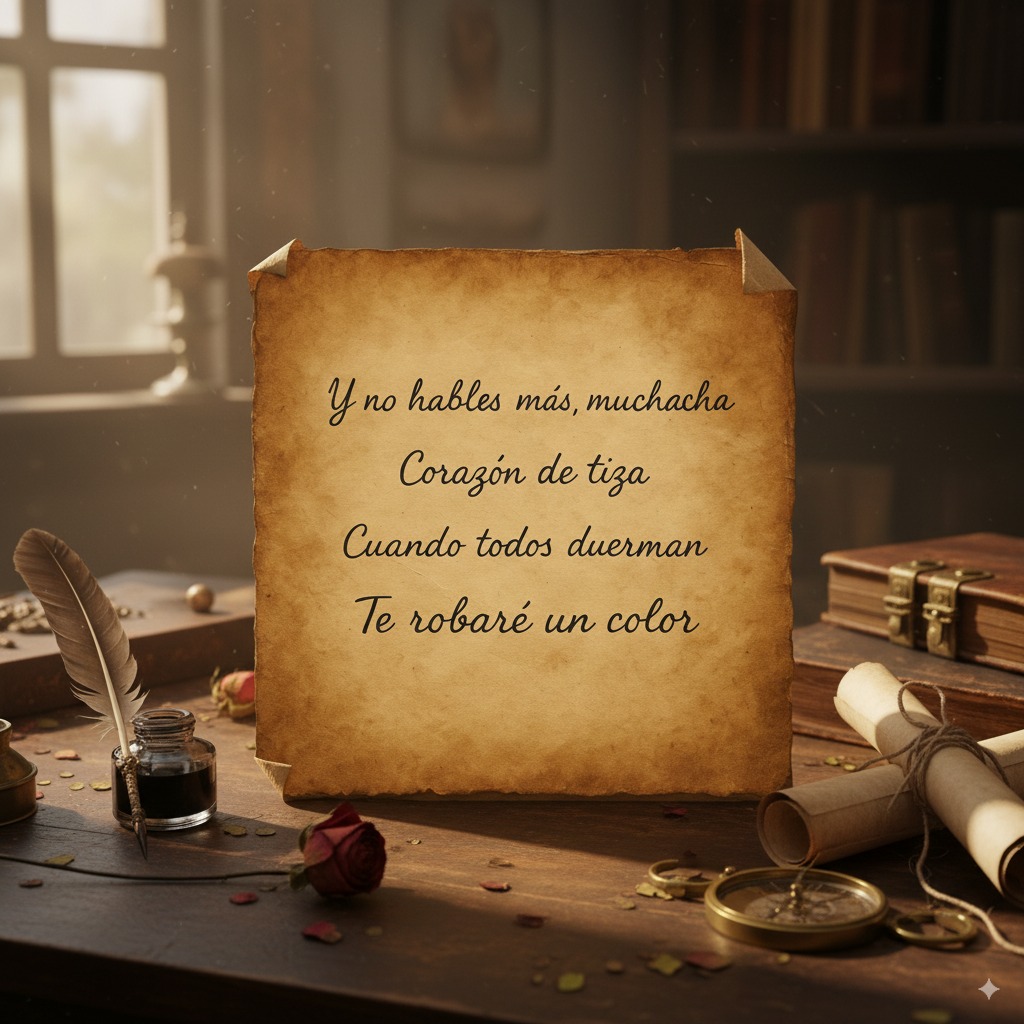

Spinetta and the delicate dawn of Muchacha

(1969)

If one were to trace a constellation of sonic genius, the year 1969 would burn among its brightest stars.

It was a kaleidoscopic explosion, a convergence of revolutions yielding imperishable monoliths of sound.

And there, in that firmament, gleams Spinetta’s ethereal sculpture:

Muchacha (ojos de papel)

. A jewel perhaps whispered of more softly beyond Latin shores, yet absolutely foundational to its very soul.

It was not only the opening track on Almendra’s debut album, but became a foundational anthem of Argentine rock, ranked by many critics as the second most influential song of the genre.

In it, Spinetta unleashes a shower of enchanted metaphors:

eyes of paper

, skin of rayon

, heart of chalk

, breasts of honey

, I’ll steal a colour

.

Images that float between irresistible tenderness and delicate eroticism, still fresh and piercing decades later.

Its power lies in fragility, in what can vanish in a breath, and at the same time it opens windows onto the oneiric and the surreal.

Almost twenty years later, Spinetta himself wrote an introspective text entitled “Muchacha ojos de papel: desintegración abstracta de la defoliación” , where he revisited those images with a philosophical, architectural tone. He reflected on codes of desire that had sprung from youthful innocence, but which in maturity revealed their full complexity.

That ability to conjure the human and the fantastic in a single poetic gesture is what makes “Muchacha” an early miracle, brief yet eternal.

This work was sensual and disruptive for its time, with a poetic delicacy that makes it timeless.

Muchacha, ojos de papel, don’t run away, stay until dawn…

Undress, there is no time…

—Muchacha (ojos de papel)(1969)

With hindsight, the song can also be read in another light: it pulses with a possessive, imperative tone more visible today; even a hint of machismo by contemporary standards. Yet it feels faint compared with the rhetoric of so many tangos about “percantas”. And there lies part of its interest: in that coexistence between the language of love and a plea that, under a magnifying glass, edges towards imposition. Each reader, each listener, will decide from where to approach it.

Still, one should never mistake sawdust for dulce de leche. There are those who can still tell the original from the copy, even the caricature from the copy, just as one does not savour Baileys in a Bohemian crystal glass in the same way as in a rough plastic cup. Spinetta’s originality lies in having turned rock into poetry without renouncing intimacy.

From crystal to plastic practicality: Karol G and Feid

Half a century later, popular lyrics speak another language. Where Spinetta built suggestive, metaphorical sensuality,

Karol G and

Feid, both Colombians from Medellín, released Verano rosa

in June 2025, with a radically different register.

Estoy a ley de una señal, márcame al celular…

—Verano rosa(Karol G & Feid, 2025)

Reading note: here only the opening verse is cited; in the following ones the temperature rises to a point that might unsettle certain readers.

Although its melody is not as easy to hum as Muchacha

’s, it has an undeniable rhythmic pulse and so is danceable.

In that trance, those moving frenetically to it might not notice the explicit message that unfolds throughout the song,

especially if they are not fluent in Spanish.

Misunderstandings should be dispelled: when Karol G and Feid sing

Que tú me corres a otro nivel, baby, responde, no seas cruel

,

they are not alluding to

Ben Johnson;

and when they invite

Volvamos la casa como un motel, así que alista las Duracell

, they are not suggesting watching a

Champions League final

on an 85-inch screen with a flat remote control.

Humour, cheek and sexuality course through the lyrics, explicit and unfiltered.

Copy, caricature or simply another language of desire? Perhaps the metaphor of the glass fits once more: the delicacy of crystal and the practicality of plastic neither seek nor produce the same experience. Spinetta was original because he invented a way of singing intimacy in his time; Karol G and Feid are original because they translate that intimacy into the urban, globalised and youthful key of their own. Each reader may judge whether intensity has turned into immediacy, whether poetry has become explicit, or whether, ultimately, they are simply different vessels for the same thirst.

And if someone really believes there is poetry in Verano rosa

, or genuine metaphor, perhaps they would benefit from a warm bath

in the discography of Sabina.

Incidentally, if anyone wants to contrast the two works directly, they can listen both to the delicacy of

Muchacha (ojos de papel)

and the immediacy of

“Verano rosa”

.

Paradoxically, our critical reading may do nothing more than increase the play count of the more recent song.

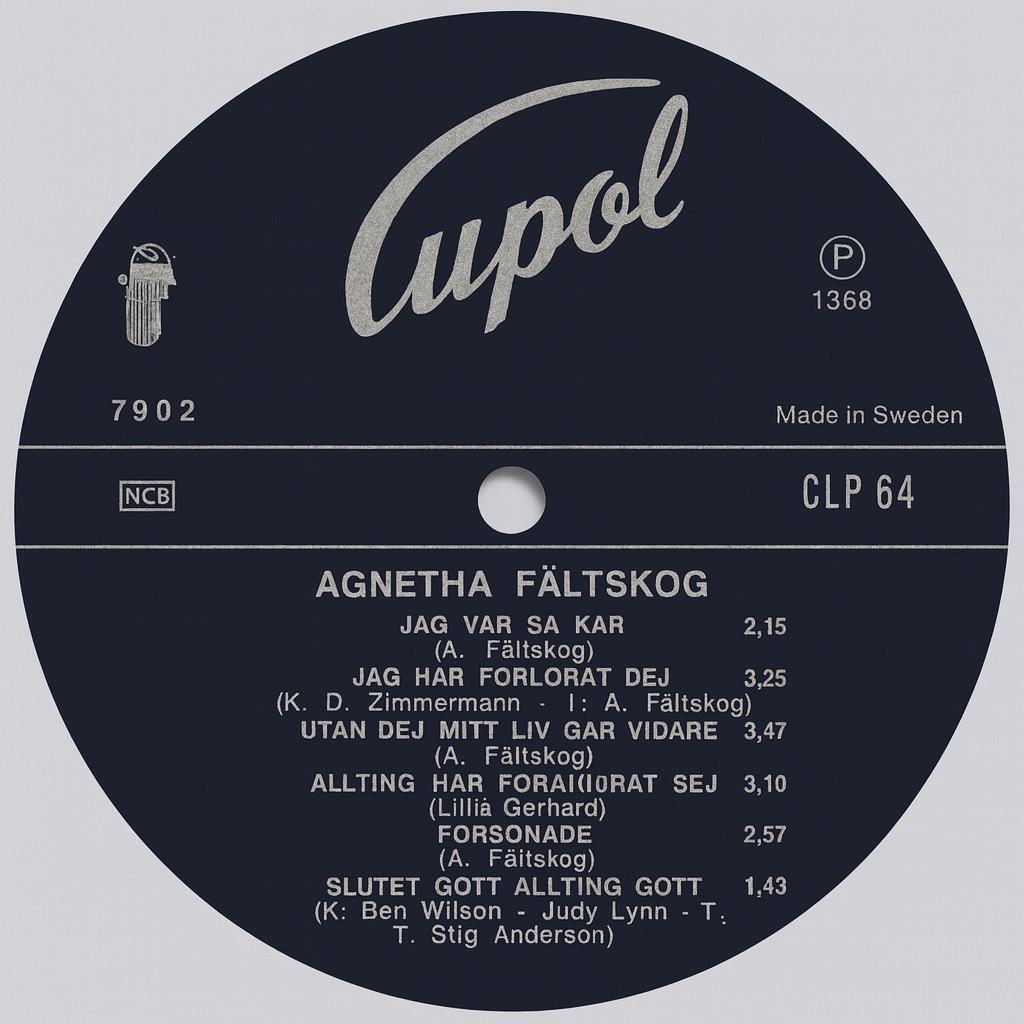

4. Agnetha: An Independent Path

ABBA, a phenomenon that deserves its own chapter, were neither the start nor the finish of Agnetha Fältskog’s story. Long before that, in a teenage bedroom in Sweden, she was writing her own songs. And the story carried on, with the same will, long after the quartet left the stage. I will not dwell on ABBA here; there will be plenty of time for the seventies.

Before ABBA: the rise of a young star

She set off early and on her own terms. At seventeen, in 1967, her song Jag var så kär

(“I Was So in Love”) reached number one at home. Not a flash in the pan, the start of a solid run as a noted singer-songwriter in Sweden. Hit followed hit in her own language; radio and television kept calling; a loyal audience grew around the schlager tradition and Scandinavian pop. By 1971 she was known well beyond the charts: her wedding to Björn Ulvaeus was billed by the press as “the wedding of the year”, a clear sign of the wave that was coming.

Tip: choose the highest available resolution and listen on good speakers or headphones to appreciate the sweetness of her voice.

An Unmistakable Voice of ABBA

Agnetha joined ABBA with a path already drawn, with a clear identity and a strong background. In the whirlwind of the quartet, her voice went with the flow but never disappeared in it. When the adventure ended in 1982, it did not feel like a final curtain, more the beginning of a different route.

After ABBA: a Path of Her Own

Agnetha took back the reins of her career with determination. The eighties witnessed her international reinvention.

Wrap Your Arms Around Me

(1983) and

Eyes of a Woman

(1985) both bore witness to her continuing relevance, and met with resounding success in Europe.

If you’re watching on your phone, it’s best enjoyed in landscape (horizontal) and with headphones.

She even tried her hand at cinema with the film

Raskenstam

.

After

I Stand Alone

(1987), she chose a long silence, almost two decades.

A conscious retreat, far from the spotlight.

Her return was not nostalgia. It was affirmation.

My Colouring Book

(2004), a tribute to classic songs, confirmed her refined interpretative craft.

In 2013, she surprised with

A

, contemporary pop with new material that became a resounding success.

And in 2023, with

A+

, she offered the ultimate proof: her voice still shines.

Her artistic judgement keeps the unshakeable personality of someone who has always known who she is.

In the end, the essence is simple: a girl who started young with her own songs, lived the intensity of a world-famous group without losing herself, and chose her moment to return. On her own terms. Simply, Agnetha Fältskog.

5. Karen Carpenter: A Voice that Stayed

There are voices, and then there was hers. The one that came from a girl born in New Haven, back in March 1950, a voice the world would never quite get over.

To hear Karen Carpenter was to receive something personal. It wasn’t loud. It didn’t need to be. It was low, warm, like velvet. Like lamplight on a dark evening. You felt it before you even understood it.

That warmth wasn’t taught. It was in her. A gift, or maybe a language only she knew how to speak.

People talk about her technique (the perfect pitch, the gentle vibrato, the breath placed just so) but that wasn’t what you noticed. What you felt was something else. A quiet understanding. A comfort that held hands with sadness. She didn’t just sing the words; she trusted you with them. As if each line were a secret meant only for you.

With her brother Richard as The Carpenters, they didn’t just make hits. They made a home out of sound. Close to You, We’ve Only Just Begun, Rainy Days and Mondays are just some of their narratives: they weren’t just songs, but promises. They were a hand on your shoulder on a hard day. They were nostalgia you could hum.

She didn’t sing to impress. She sang to hold you. Her power was in restraint, in the softness that somehow said everything. She used messa di voce not as a technique, but as an embrace. And underneath it all, there was always that touch of sorrow. A vulnerability that made her sound not perfect, but true.

Carpenters’ cover of the 1967 hit by Herman’s Hermits, written by Les Reed and Geoff Stephens. Featured on the album

A Kind of Hush(1976), the track showcases Karen Carpenter’s warm lead vocal and Richard Carpenter’s polished arrangement.

Her own story was shorter than it should have been. Marked by a quiet struggle that stood in contrast to the assurance in her songs. But when her music plays now, something still happens. Time slows. That voice returns, clear, gentle, deeply human.

It’s like that low, grey sky on a Sunday: proper comforting, but with a real ache of nostalgia running through it. You can’t help but love it precisely because you know it won’t stick around.

Five decades on, Karen is still with us: her greatness was never about excess or ornament. It was in the way she sang with plain honesty, in the way she spoke straight to the listener’s soul.

The world keeps pretending and shouting, but to me her voice feels like a swan moving slowly on a still lake. I suppose that is why it sounds so calming. Almost like a friend who understands without saying anything at all.

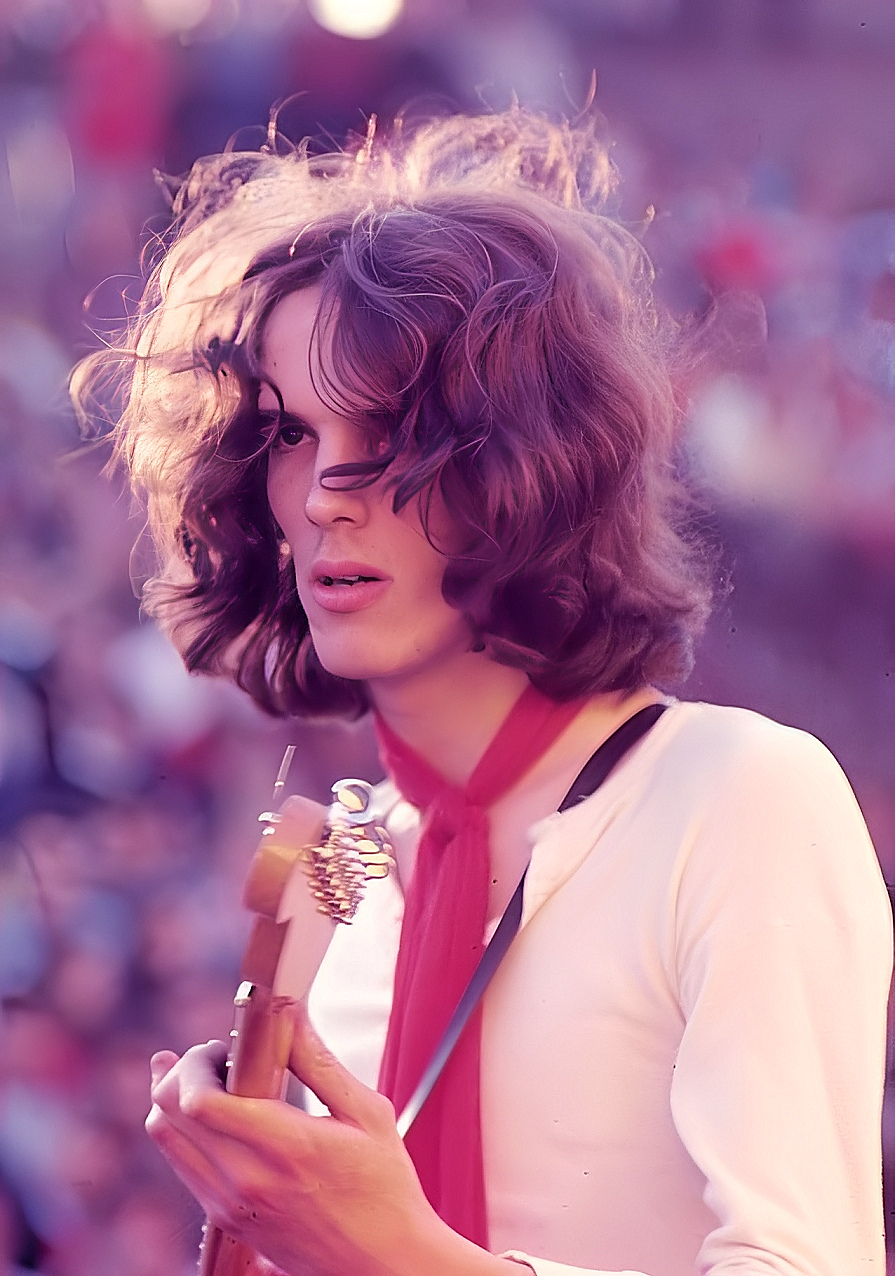

6. Roger Hodgson: The Melodic Goldsmith of Supertramp

Some bands find their sound in the elegant clash of two strong personalities. Supertramp is one of them. Rick Davies contributed rhythmic grounding and harmonic sense rooted in blues and jazz; Roger Hodgson added flawless melodies, pop sensitivity and that unmistakable high-pitched voice. Out of this balance came a catalogue that has stood the test of time. For several generations, it remains a voice that can be recognised instantly.

The nomenclature of the art-rock pioneers Supertramp has a decidedly literary origin, born from a period of reinvention. Initially performing under the rather underwhelming moniker Daddy, the fledgling group found themselves requiring a change to avoid confusion with another act.

It was guitarist and lyricist Richard Palmer who first came up with the idea of calling the band Supertramp. The spark came from a book he admired, Welsh poet W. H. Davies’s 1908 memoir The Autobiography of a Super-Tramp

, a favourite also of keyboardist Rick Davies. Its pages spoke of freedom, restless journeys, and lives lived on the margins of convention. Those same themes echoed the band’s own early spirit, still in search of direction yet unwilling to be tied down.

The name stuck. It had a playful ring to it, hinting not at a drifter but at a traveller who knew the road, toughened by experience yet fuelled by imagination. It seemed to sum up, in a single stroke, the spirit of adventure that would later shape their sound.

After two early albums that almost went unnoticed, the compass was set with Crime of the Century

(1974)

and, above all, with Breakfast in America

(1979).

In time, Supertramp left behind expansive progressive rock and honed a pop of fine detail. Clear pulse, tight arrangements. And there was Hodgson, again and again: “Dreamer” and “School” with their drive, “Give a Little Bit” with its open twelve-string, “The Logical Song” and “Take the Long Way Home” with that whistle etched in memory, “It’s Raining Again” as a natural closer, and “Fool’s Overture”. A bouquet that, in itself, explains the devotion of the audience.

The peak came with Breakfast in America

: songs that hook at first listen and return when you least expect it. Simple as that, effective as ever.

Breakfast in Americatour. Supertramp played four consecutive shows at the venue, 29–30 November and 1–2 December 1979, which were filmed and recorded; from those nights came the live album

Paris(1980), with most of the material drawn from 29 November, and, decades later, the expanded edition

Live in Paris ’79.

If you’re watching on your phone, it’s best enjoyed in landscape (horizontal) and with headphones.

“The Logical Song” was honoured in 1980 with the Ivor Novello Award for Best Song, Musically and Lyrically, a peer-to-peer recognition among songwriters that confirmed what the ear already knew: behind that high-pitched voice was a lyricist of depth.

In 1983, Hodgson decided to close a chapter: prioritise family, record solo, and leave Davies to carry on with the Supertramp name.

The band continued with Brother Where You Bound

(1985) and

Free as a Bird

(1987),

went on hiatus in 1988 and regrouped in 1996, but without restoring the original partnership.

The solo debut was promising: In the Eye of the Storm

(1984) showed range, polished production and certifications that backed the momentum (platinum in Canada).

Hai Hai

(1987) left him less satisfied and, to make matters worse, a domestic accident fractured both wrists and kept him away from the piano for quite some time.

He came back gradually: Rites of Passage

(1997) returned him to the stage, and

Open the Door

(2000), recorded in France with an unmistakable Breton air, left perhaps his most inspired studio work of maturity.

Meanwhile, ASCAP recognised him in 2006 and 2008 for the enduring radio presence of “Give a Little Bit” and “Take the Long Way Home”.

If you’re watching on your phone, it’s best enjoyed in landscape (horizontal) and with headphones.

By the 21st century, Hodgson recalled his past without being trapped by it. He appeared at the Concert for Diana (Wembley, 2007), mentioned in his

Spanish biography, with a medley that moved many;

took part in Night of the Proms (2017) and, in 2018/19, celebrated the 40th anniversary of Breakfast in America

with a tour that proved the songs still breathe in the present.

No secret alchemy: unmistakable timbre, singable melodies and lyrics that, without grandiloquence, allow themselves a philosophical question.

The label of “exquisite co-leader” is justified for two reasons: first, because his songs never sounded like filler; they were vertebrae of Supertramp’s identity. Second, because his studio perfectionism, sometimes criticised as “polished”, translated into live shows of the highest order, where emotion was never buried beneath sound engineering. At seventy-five, Hodgson retains a rare virtue: his work ages without wrinkling. Every time the opening bars of “The Logical Song” are heard, or the twelve-string of “Give a Little Bit” comes in, one understands why: there was craft and there was soul; technique and wonder. And that combination, in pop, is what endures.

7. Ann Wilson: Power and Voice

From the Nordic calm of Agnetha we leap to the Californian sun: in that same year of 1950 was born the one who would embody the commanding strength of hard rock. Ann Wilson, a girl from San Diego who, together with her sister Nancy, would claim a territory long closed to women: hard rock. At the helm of Heart, she broke into a male-dominated universe to prove, with a wide-ranging and richly nuanced voice, that female energy could not only pulse within it, but become its very heart.

Her voice, close to the operatic, gave the band a very distinctive stamp in the seventies. The blend of strength, drama and warmth meant that audiences remembered her at every concert. With Heart, Wilson not only filled halls and stadiums: she also left a mark that inspired many singers who came after.

Stairway to Heaven. Jason, son of the legendary drummer John Bonham, took his father’s place on drums, while a choir in bowler hats evoked the accessory that had been part of his personal trademark.

It was an epic moment: the Wilson sisters, essential figures of hard rock, were returning with reverence and power to Zeppelin what its music had given them. The emotion of Robert Plant, Jimmy Page and John Paul Jones, present in the royal box, was palpable: tears, smiles and a standing ovation crowned what many consider the most moving tribute ever offered to the band.

Tip: when watching the video, set the quality to the highest available resolution and enjoy it on a good sound system or headphones to feel the full power of this historic performance.

If Ann Wilson embodies the power and marble of hard rock (1950), the next section turns the dial towards another way of guarding rock: the economy and the highway of a great artist born in 1950.

8. Tom Petty: The Road and the Truth

Born on , he joins this series by both date and merit.

Tom Petty was, for many of us, not a sudden revelation but something that grew slowly. My ear, tuned to the complex shapes of late-sixties British progressive rock, first heard in his radio staples: American Girl, Refugee, nothing more than pleasant sing-alongs.

It wasn’t until the late 1980s that I began to appreciate him. In that plain voice I caught echoes of a later Dylan. Not the poet chasing endless lines, but a man speaking with a clearer, straighter truth. It felt like scraping away clutter until only the solid heart remained. What never changed was his honesty, touched with something of Springsteen’s spirit, unmistakably American and giving his songs a lasting weight.

That was the moment it clicked for me. He wasn’t just playing rock and roll; he was guarding its meaning.

He was finding his own ground, somewhere between big, classic rock and smaller, folk-coloured songs. With The Heartbreakers he was not chasing fashions. He was shaping a sound that felt timeless and close at the same time, like a jacket that had already been part of your life.

And that voice? It was the same one I had half-ignored on the radio for years, but now I could hear the man behind it: both personal and universal. Even his stubborn battle with MCA Records, a story I once dismissed as industry folklore, now sounded like part of the same truth that ran through his songs.

He wrote for himself, but he was also keeping the flame for everyone else. We still carry Free Fallin’, Learning to Fly and I Won’t Back Down as part of our common songbook.

Song written by Tom Petty and Jeff Lynne, featured on the album

Full Moon Fever(1989). It was the first track they completed together for the record. The single reached number 7 on the Billboard Hot 100 in January 1990, becoming one of Petty’s most enduring hits. The video shows various Los Angeles settings, including a sixties-style pool party, an eighties skate park, and a young woman drifting through different urban landscapes.

His place in the Traveling Wilburys told the same story. George Harrison, needing a B-side, gathered with Jeff Lynne at Dylan’s studio; Roy Orbison wandered in, and Petty appeared because of a guitar Harrison had left at his house. The “forgotten guitar” was really just a gentle excuse: Harrison wanted his friend there.

Though the youngest, Petty was never a junior. He was the bridge, the modern pulse, the American road in flesh and song. He brought the raw drive of the Heartbreakers to a table of giants, yet with an integrity they all respected. He was a purist who understood rock and roll’s past as much as its future.

And among all those voices, it was Petty’s rough honesty that often held the music together. His tone gave the songs a backbone that balanced the weight of the older legends. What came out of it was rare and simple: music as friendship, the kind that happens once and cannot be staged again.

9. Chris Norman: Frontman of Smokie

Among the class of 1950, Chris Norman is a name I return to. You hear a few bars and you know who it is. In time that tone came to stand for European soft-rock. He was a music-mad kid who started out with his mates, tinkering after school, unaware they were inching towards Smokie. Once there, he found a melodic touch that refused easy labels, not quite pop and not quite rock, a quiet alchemy that leaves the chorus hanging in the room.

I had been a fan for ages, but

Stumblin’ In

with

Suzi Quatro

in 1978 pulled me closer. I went back through the records and the duet made complete sense, unexpected on paper and absolutely right in the ear.

Stumblin’ Instill sets crowds alight. On 4 July 2025, the Auckland Philharmonia joined forces with Australian DJ CYRIL for a euphoric remix, featuring Masha Mnjoyan and Nate Dousand. The song, originally recorded in 1978 by Suzi Quatro and Chris Norman (both born in 1950), proved once more its timeless appeal.

Smokie’s run gave us songs that never really left:

If You Think You Know How to Love Me

,

Living Next Door to Alice

,

Lay Back in the Arms of Someone

.

They sit midway between tenderness and yearning. No surprise they slipped onto playlists the world over.

Changing All the Time. It reached No. 3 on the UK Singles Chart and was a hit across several European charts.

If you’re watching on your phone, it’s best enjoyed with headphones.

When CDs took over in the mid-eighties, the chase began. Here, each copy felt hard-won. I remember the rounds of record shops, the wait for imports, the catalogues with pencilled notes beside stubborn gaps. The patience was part of the pleasure. Every disc felt like a small victory over time and distance.

To me, Chris Norman still spells refuge. A 1950 voice that carries the same mixture of sweetness and steel that won so many hearts.

From Yorkshire to Beckenham: if Norman (1950) brought the warmth of the bar to the radio, Frampton (1950) carried the stage to the listener’s ear.

10. Peter Frampton: The Boy Prodigy with the Talk Box

In post-war Beckenham, a young Peter Frampton was discovering a sound that felt different from anything taught in classrooms or concert halls. Not in conservatories, but in bedrooms, where he absorbed the raw energy of American rock ’n’ roll.

He didn’t just copy the riffs of Buddy Holly and Gene Vincent; he caught their spirit and made it his own. By sixteen, he was the golden boy of The Herd, a prodigy with the skills of a veteran and a face that made the press swoon. A pop star, yes, but with fingers restless for more.

Humble Pie: Learning in the Fire

The call for greater depth came when Steve Marriott of the Small Faces drew him into the birth of Humble Pie. By 1969 he had left the poster-boy role behind and stepped into the rougher language of the blues. I can picture those nights in crowded halls across Britain, where his playing found a balance between grit and grace. Humble Pie soon gained a reputation as a band you had to experience live.

The Leap into Solo Work

In 1971 he set out alone.

Wind of Change

,

his first album, felt less like a debut and more like a gathering of friends,

Ringo Starr,

Billy Preston, and others passing through

to lend their touch. It was the beginning of his own path.

Frampton. The song became one of Frampton’s signature tracks, later immortalised in the live version from

Frampton Comes Alive!(1976), which turned into a defining moment of 1970s rock.

1976: Frampton Comes Alive!

When the live record came out in 1976, I felt it was part of the time we were living through. On stage he was anything but distant; he spoke with the crowd and carried them along. His guitar could sound tender or sharp, and the talk-box effect gave it an odd, speech-like colour, as though the instrument had found its own voice.

For me,

Show Me the Way

was the invitation, the piece that made you lean closer.

Baby, I Love Your Way

felt like the glow of late evening, sung as if it were meant for a handful of friends.

By the time

Do You Feel Like We Do

arrived, the hall had already turned into a single choir.

Songs like these didn’t end when the concert did; they carried on in our own singing.

Frampton(1975) and gained massive popularity through the live version on

Frampton Comes Alive!(1976). More about the artist: Peter Frampton.

A Musician among Musicians

His contacts could have filled a hall of fame: George Harrison, David Bowie, Harry Nilsson, Ringo Starr. Yet what earned him their respect was not headlines or column inches, but the playing itself, the kind of gift fellow musicians recognise at once.

Strength in Later Chapters

When Frampton spoke openly in 2019 about his rare degenerative illness (IBM), his life took on a different note. Strength was no longer measured on stage alone. It showed in his courage, in the humour he held on to, in the grace with which he faced the days ahead. That resilience became part of his music’s afterglow, enduring and quietly powerful.

A Living Legacy

The prodigy. The pioneer. The man with the talk box. His music, casting its spell since the 1970s, continues to find new ears and new hearts. Peter Frampton endures, not only as a musician, but as a true British icon.

11. Jim Peterik: From Vehicle

to Eye of the Tiger

Born in Berwyn, Illinois in

1950,

Jim Peterik first made waves with

The Ides of March.

Their single Vehicle

stormed the U.S. charts in 1970, driven by brass riffs and teenage bravado.

But it was in the 1980s, as co-founder of

Survivor, that Peterik wrote himself into cultural memory.

Vehicle. The lyrics were inspired by an ambiguous relationship, in which Peterik felt he was being used merely as a “vehicle”. Its distinctive horn section led many listeners to mistake the track for the sound of Blood, Sweat & Tears, also popular at the time. Released in March 1970 by Warner Records.

When Sylvester Stallone requested a theme for

Rocky III, Peterik and

Frankie Sullivan came up with

Eye of the Tiger

.

The song achieved more than just topping the charts and winning awards; it became one of those rare instances of perfect symbiosis between music and cinema.

The guitar riff and defiant chorus are inseparable from Rocky’s training montage; the film cannot be recalled without the song, nor the song without the film.

In that sense, Peterik composed one of the ten most powerful marriages of song and movie in modern history.

Beyond Survivor, Peterik’s pen shaped the sound of 38 Special, Sammy Hagar, Cheap Trick and even The Beach Boys. A craftsman, mentor and performer, he remains proof that a single song, at the right moment, in the right film, can etch a musician’s legacy forever. And for that reason, this baby of 1950 deserves his place in the list.

12. Carl Palmer: The Rhythmic Architect

When I wrote about

Jim Peterik,

I recalled becoming aware of his band in the early eighties, almost by accident, discovering a voice that would later power

Eye of the Tiger

.

But Carl Palmer?

That was a different story altogether. No introduction needed. By then, I was a teenager and their music was already part of my world thanks to a friend from the chess scene who had an absolute ear for music.

Carl Palmer came into the world on 20 March 1950 in Birmingham, England’s busy industrial centre. His home was full of music: grandfather on drums, grandmother on violin, father singing whenever he could. Surrounded by that, it was no surprise that by his teens Carl was playing with local dance groups.

Then came the decisive spark: watching Gene Krupa and Buddy Rich, he realised that percussion would not just accompany his life; it would define it.

The late sixties became his first testing ground, with The Crazy World of Arthur Brown and Atomic Rooster. And then came the call from Keith Emerson and Greg Lake. What might have been one more progressive project turned into Emerson, Lake & Palmer, a band that dared to be as ambitious as my own musical hunger in those years.

Palmer kept things together. Emerson could take off on the keys, Lake could lift everything with his voice, but Palmer was the one who kept it steady.

Put on Tarkus

or

Karn Evil 9

and you can hear him steering, no matter how wild things get.

He didn’t limit himself either: he hit drums, gongs, timpani, whatever it took to push the music higher.

By the time the eighties rolled in, he had changed direction. With

John Wetton,

Steve Howe

and

Geoff Downes

he formed

Asia.

The music was leaner, built for radio, but his heartbeat was still there.

Heat of the Moment

shows it in the very first bars. That opening beat is proof of how something simple, played with conviction, can become unforgettable.

Fanfare for the Common Man. Recognised as one of the great drummers of his generation, Palmer cites the influence of Buddy Rich and stands alongside fellow legends such as Neil Peart (Rush), Bill Bruford (Yes), and Alan White (Yes). Palmer rose to worldwide fame as the drummer of Emerson, Lake & Palmer and later of ASIA.

Looking back, I see why his story resonated so quickly with me. Peterik taught me that a single voice could carry hope and drama. Palmer showed me that rhythm itself could be a voice: sometimes complex, sometimes stripped down, but always decisive. That is why he remains, for me, not just a drummer, but the pulse behind two generations of sound.

Farewells (Musicians)

1. Eduardo Fabini (1882–1950)

On 17 May, Eduardo Fabini,

the national symphonist par excellence, died in Montevideo. With works such as

Campo

and Mburucuyá

he had fused folklore with the orchestra, giving Uruguay a musical identity of its own. His legacy is such that today his portrait appears on the

100-peso Uruguayan banknote.

2. Francisco Lomuto (1893–1950)

On 23 December, tango lost Francisco Lomuto, pianist, conductor, and the mind behind popular pieces like Dímelo al oído

. His orchestra gave life to the Buenos Aires salons for decades, its sound woven into the memory of the Río de la Plata. The tangueros de ley, as the true old guard of tango are called, keep that memory alive as part of the golden years.