1950

The first heartbeats of a new era

A Time Capsule in Music Curated by JGC

Musical shortcut?

Here you’ll find a cultural introduction to the year 1950. If reading is not your thing, or you are short on time, you can jump straight to our music selection using the YouTube or Spotify buttons below.

A selection based on quality and significance, not on mass trends.

1. Introduction

Every project needs a compass. This introduces the general sense of Insight 1950 and explains how it is organised: a main cultural narrative and a parallel archive of music and chess ephemera. It is not an encyclopaedic text, but a personal look at the echoes and changes of that year.

To learn how the idea began, what principles guide it, and why 1950 still matters today, explore the project’s introduction.

2. Rebuilding After the War

By the start of the decade, five years had passed since World War II had ended. Even so, its effects were still everywhere. Cities in Europe and Japan were rebuilding brick by brick, and life was only just getting back to something that felt like normal. Culture, of course, took time to return; and music was no exception.

Let’s be honest: people had more pressing concerns. Food, shelter, clean water; those came first. Music wasn’t at the top of the list. A lot of concert halls and recording spaces had been damaged or used for the war. Equipment was outdated or hard to replace. And funds? Mostly directed to basic needs.

In Western Europe, the Marshall Plan brought some relief. With outside help, factories reopened, jobs returned, and certain sectors began to breathe again. But when it came to music, things moved slowly. Most records stayed local, and the idea of songs crossing borders just wasn’t part of the reality yet.

3. Twelve Births of 1950 (Musicians and Chess Players)

This section brings together two parallel selections of people born in 1950: one of musicians and another of chess players. The criterion is their historical and artistic or sporting impact, inevitably tinged with personal bias. We were drawn to the magic of twelve: like the twelve semitones that complete the chromatic scale, or the twelve pieces with which each side begins battle on the sixty-four squares, eight pawns and four minor pieces.

To preserve the flow of this cultural introduction, both lists are presented on separate pages, with photographs and links. If we have overlooked someone of comparable relevance, suggestions are welcome via the contact button at the top of the page.

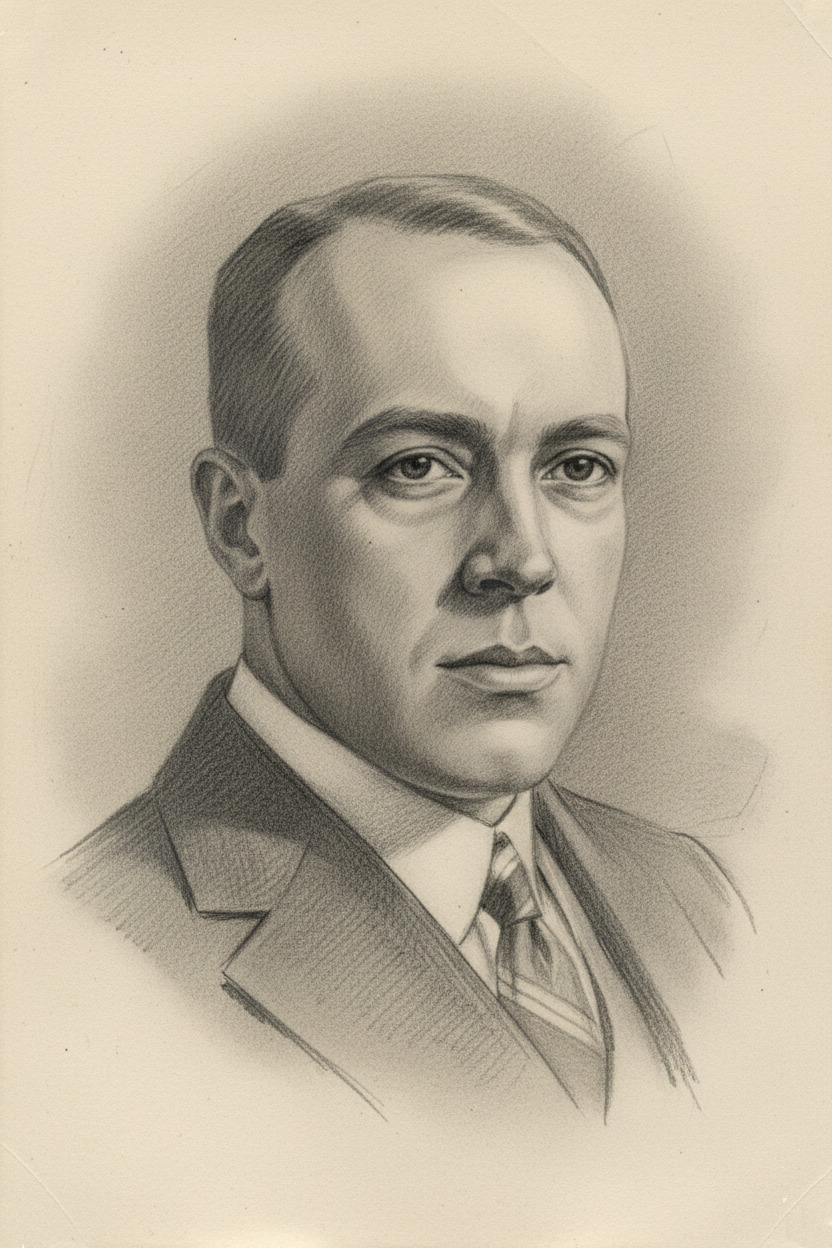

4. Edgar Rice Burroughs: A Life As Intense As Tarzan’s

A quarter of the twenty-first century has already gone by, and 150 years have passed since his birth in Chicago. The image of Edgar Rice Burroughs still lingers in popular culture, even for today’s so-called “snowflake generation”, though not always under his real name. One way or another, the lianas remain as strong as when they carried his most famous creation, Tarzan.

Burroughs did not reach success by any straight path. A soldier without glory, an unsuccessful rancher, a pencil salesman and a railway clerk, he seemed destined for mediocrity until he found his true calling. In 1912, under the pen name Norman Bean, he published the story serialized as

Under the Moons of Mars

(later released in book form as A Princess of Mars

), the opening chapter in the Martian saga set on

Barsoom,

a fictional version of Mars created by the author himself.

That same year, Tarzan was born, a character who would soon leap far beyond the printed page and grow into a worldwide myth.

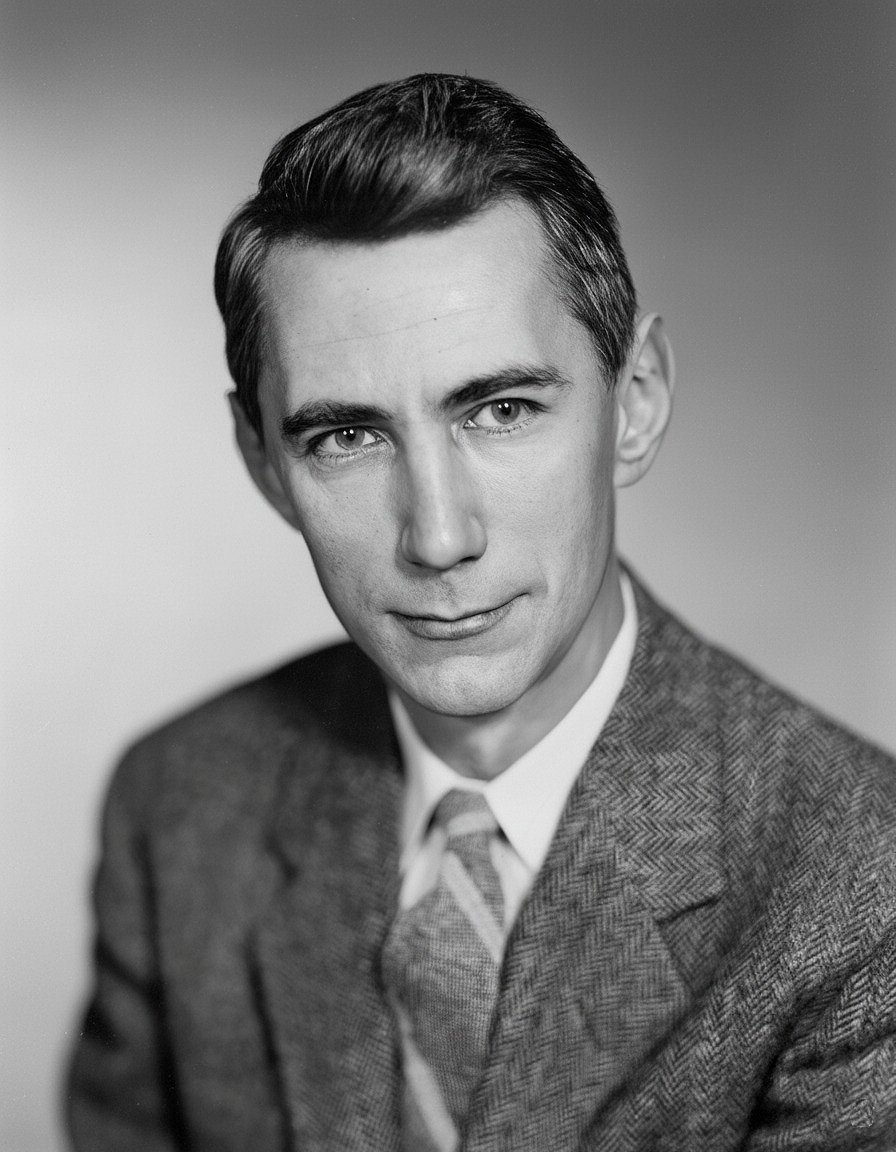

Jungle Tales of Tarzan, 1919). Original public domain source: Wikisource. Digital recreation guided by JGC.

Over nearly four decades, Burroughs wrote close to ninety novels that carried his readers into African jungles, red planets and underground worlds. His style, direct and fast-paced, blended action, exotic settings and boundless imagination. He also grasped the power of new media: he founded his own publishing company, kept control of adaptation rights and became a pioneer in literary tie-in merchandising.

Burroughs was not only a storyteller. In the middle of the war, as he neared seventy, he became a correspondent in the Pacific, following the troops from Pearl Harbor onwards. He came back alive, yet deeply marked by the experience.

In 1950, Edgar Rice Burroughs’s life came to a close in a neighbourhood of the San Fernando Valley in Los Angeles, California, only months before his seventy-fifth birthday. And seventy-five years later, his work continues to be reissued and reshaped in every imaginable format.

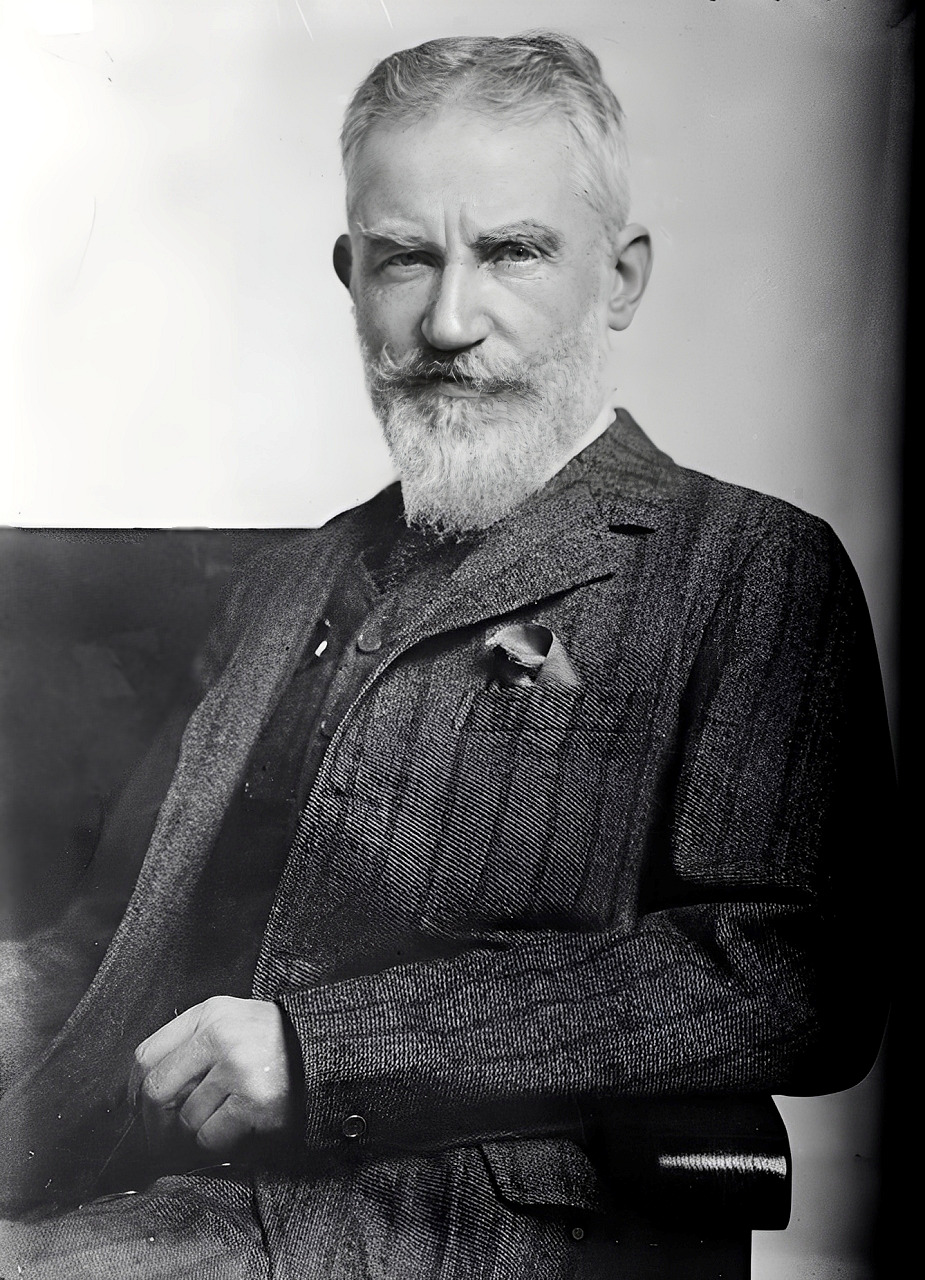

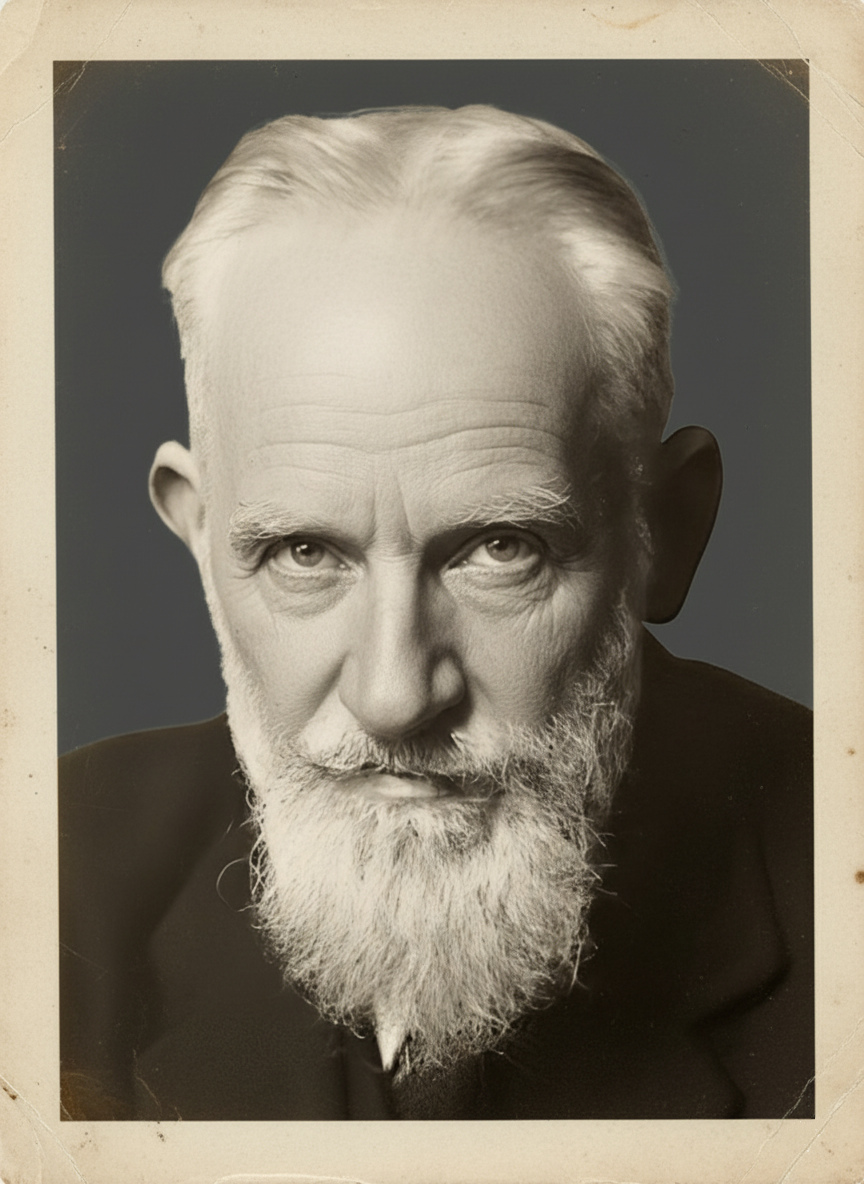

That same year also saw the curtain fall on another giant of letters. From the jungles of Tarzan and the red skies of Barsoom we now turn to a very different stage: the sharp wit of George Bernard Shaw, who wielded words not to imagine new worlds, but to question the one he lived in.

5. George Bernard Shaw: At the Hinge of Two Centuries

He was not, at least in my opinion, the kind of man who could ever be neatly contained within a single definition.

Playwright, critic, essayist, visionary, nonconformist: he was all of these, and more besides. He was born in Dublin in 1856, the same year as Sigmund Freud. He appears in this extended cultural introduction because Shaw died in November 1950. With these dates in mind, we can see that he lived long enough to witness two world wars, the rise and fall of empires, the first aeroplanes in the sky, the golden age of cinema, Uruguay’s celebrated football triumphs, the telephone, the radio, and even the earliest computers. To my knowledge, very few writers spanned centuries with such breadth. He was, without exaggeration, the last of the great Victorians and, at the same time, a witness to the birth of what we now call the modern age.

Shaw's success can be seen as something that came easily to him, which is something that is evident when observing his achievements and career path. Yet his early life was nothing of the sort. I sometimes picture it with a touch of sympathy: a young Irishman stepping off a train in London, not much in his pockets beyond stubborn determination. Like many of his countrymen, he had left Dublin in search of recognition. Instead, he endured years of frustration, living off scraps of journalism and anonymous criticism, gradually shaping his voice in essays, and eventually on the stage. As far as I’m concerned, when recognition finally came, it was not luck but persistence: hard-won, almost painfully so.

Shaw’s career is often reduced to two glittering milestones: the

Nobel Prize in Literature (1925)

and the

Academy Award for Best Adapted Screenplay (1938)

for Pygmalion

.

He was the first person ever to win both — quite a feat for a self-taught Irishman with no formal university degree.

Still, prizes can mislead as much as they illuminate.

What truly mattered was his restlessness, his taste for provocation.

He kept pushing boundaries far beyond what most considered reasonable within their comfort zones.

Of course, Shaw was full of contradictions. He admired democracy, though he doubted the judgement of the masses. He supported socialism in a gradual and constitutional spirit, true to his Fabian convictions, yet at the same time he toyed with unsettling ideas such as eugenics or a radical reform of the English alphabet. There were moments when he wrote with enthusiasm about Stalin or Mussolini, even as others were already regarding them as tyrants. He also opposed vaccination, while at the same time celebrating with fervour the advances of science in other fields. These are not easy positions to justify, yet they help us to understand a complex man, both a child of his age and, in many ways, overwhelmed by it.

Shaw was never one to leave things as they were. He liked to push, to prod, to test the limits. He could be brilliant at times and reckless at others, yet he was always restless. In politics, he aligned himself with the Fabian Society, convinced that lasting change could be achieved not through violence but through deliberate, carefully planned steps. What truly set him apart was his gift for winning people over.

He brought that same persuasive streak to the theatre. At a time when English stages were clogged with sugary comedies and tired melodramas, he brought something sharper. Arms and the Man

, Major Barbara

, Saint Joan

, Man and Superman

: these weren’t just plays, they were provocations.

And he never left it at that. His prefaces, those sprawling essays he liked to tack on, could be just as bracing as the plays themselves. You might buy a ticket expecting an evening’s entertainment, but you left with questions about war, about money, about faith, about what it means to be a man or a woman. Shaw wanted theatre to sting a little: and it usually did.

The intellectual scaffolding of Shaw’s work was eclectic. Darwin shaped his sense of creative evolution. Nietzsche’s idea of the superman fascinated him, though he reworked it through his own socialist lens. His fascination with heredity led him to endorse eugenics, with the best intentions and the worst consequences. He believed humanity could improve itself by conscious design, much as breeders improved livestock: a notion that history has darkly discredited. And yet, for all his errors, Shaw never stopped thinking, never stopped prodding at assumptions. He was not content to affirm what polite society already believed. He provoked because, at least from where I sit, he saw provocation as a duty of the intellectual: to rattle, to disturb, and to force reconsideration.

For much of my life I delighted in the quick, incisive wit of the famous exchange between him and Winston Churchill, only to learn later that the dialogue was simply too good to be true.

Shaw writes: “I am reserving two tickets for you for my premiere. Come and bring a friend—if you have one.”

Churchill replies: “Impossible to attend the first performance. Will come to the second—if there is one.”

However charming the anecdote may be, it never happened, as confirmed by the official publication.

Source: The Society has preserved the text in its journal

Finest Hour

, no. 190

, “Leading Myths: WSC & GBS,” which clarifies that the exchange is apocryphal.

Shaw was never easy to pin down. That mystery didn’t lessen his influence: it made him all the more fascinating. Intellectual life is rarely neat or simple, and he embodied that truth with flashes of brilliance alongside his missteps. Figures like him matter because they dare to go where others wouldn’t even imagine. He stood with one foot in each century, between two very different worlds, and yet his voice still carries. It comes to us sharp, restless, and alive with things worth hearing.

Shaw died in November 1950, aged ninety-four. The world was completely different by then, having changed beyond recognition from the one he had been born into. He had lived through an era of discoveries, upheavals and revolutions, and had tried to make his mark on each of them in his own way.

6. George Orwell: Between Liberty and Oppression

6.1. Childhood in the Empire

Orwell’s beginning is not English. It is Indian: Motihari, 1903. The heat was close; the Empire already felt old at the edges. As a child he saw both the pageant and the cracks. That push and pull never left him. It taught him to scrape at neat stories until he hit the harder truth.

School in England tried to make him fit. Burma changed him. From 1922 to 1927 he served in the Indian Imperial Police. In uniform he wasn’t a student but part of the machine. The job put him face to face with paperwork, fear and force. He walked away. It wasn’t only a resignation; it was a refusal to keep telling a lie.

6.2. Descent into the Shadows

Hungry for experience, he sank into the underworld of need. Paris and London greeted him not as a traveller of note but as a shadow among the dispossessed; washing dishes, sleeping in shelters, drifting at the edge of sight. From that half-light his pen emerged, sharp and stripped of ornament.

6.3. From Socialism to Disillusion

Taking on a new name, George Orwell, soon to sound like a curfew bell for the powerful, he published Down and Out in Paris and London

. It was his baptism by fire, written in the ink of survival.

First an anarchist at heart, later a socialist, he wrote with fury against injustice. In the coalfields of northern England, where industry dug its claws into human flesh, he found the material for The Road to Wigan Pier

. There, theory collided with the gaunt faces of the exploited.

His path soon crossed Spain. In 1936 he joined the POUM militias to face fascism. The battlefields of Barcelona revealed another danger: the shadow of Stalinism, turning against its own. He lived through the gunfire, but not through the illusion of unity. That rupture left a scar, and from it grew the stance that would define him, his lasting rejection of Stalinism.

6.4. A Voice in Wartime

The Second World War found him at the BBC, producing broadcasts for India on the Eastern Service.

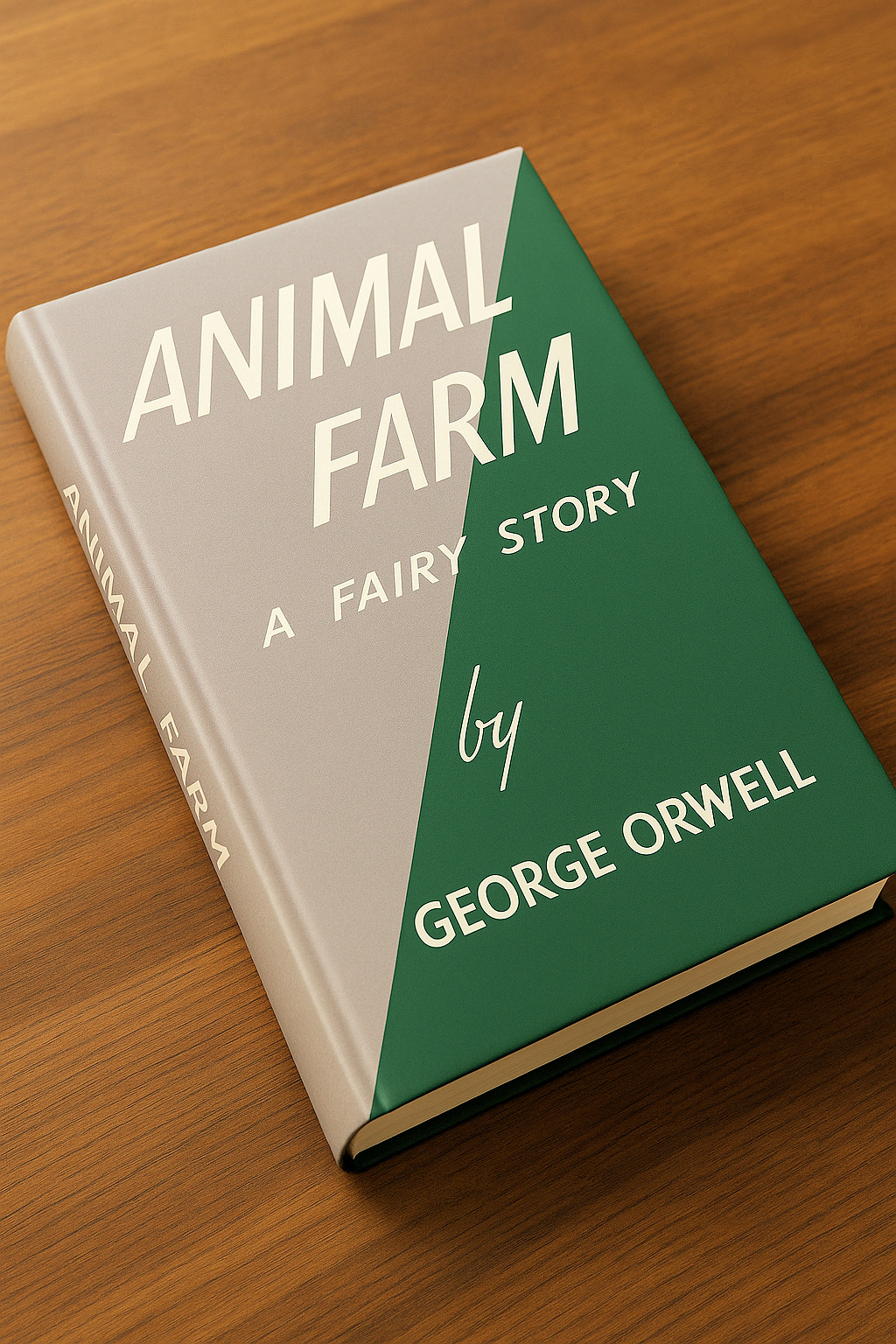

Later, at the weekly Tribune, his lucid and unsparing prose helped shape the thought of the British left. And in August 1945, when peace still smelt of gunpowder, he gave the world Animal Farm: A Fairy Story

. A fable born in a farmyard, yet exposing with chilling clarity the corruption of revolutionary ideals. The farm became a universal mirror, and Orwell at last shook free of material want.

Animal Farm: A Fairy Story(1945), published in London by Secker & Warburg. This political fable by George Orwell turned a farmyard into a mirror of human revolutions and became a classic of twentieth-century literature. The austere design (half grey, half green) reflects the tension between utopia and dystopia that runs through the work.

6.5. The Testament of 1984

Yet his gaze already pierced a darker horizon. Sick, with tuberculosis consuming his lungs, he forged his starkest testament: 1984

. Not a prophecy, but a warning chiselled into the marble of dread. Oceania was his laboratory: a realm where language twisted into Newspeak, surveillance grew godlike in Big Brother, and the human mind was violated by doublethink : words that leapt from the page to dwell in our collective fear, a universal lexicon of modern authoritarianism.

6.6. The Farewell

In the bitter London January of 1950, winter winds found him spent. Tuberculosis defeated the body, but the voice of George Orwell, once a child of India, a wanderer through Europe, a betrayed fighter in Spain, and an unblinking sentinel of freedom, did not fall silent.

He was forty-six when he died on 21 January. The illness ended his life, but not his voice. Orwell’s warning has outlived him. Each generation meets it again, a reminder that truth bends easily and that unchecked power strikes language first.

6.7. Orwell Around Us

Many readers may never have opened

Animal Farm

or

1984

.

Yet Orwell’s shadow still crosses their lives, not as a distant historical figure but as a persistent, quiet whisper in our modern discourse.

The title of a global reality show, Big Brother, came straight from his pages, its ironic twist a testament to how thoroughly his warnings have been absorbed, and at times, commodified.

So did the graffiti that warns “Big Brother is watching you”, a phrase now equally at home on a protest sign as in a cybersecurity report.

Even our language has kept his mark: words like

Newspeak,

used to decry the hollowing out of meaning by euphemism, or

doublethink,

which perfectly captures the cognitive dissonance of our political and digital age, have slipped from the page into our everyday talk about power and deception.

And from that same farmyard fable sprang a line that has hardened into a universal proverb: “All animals are equal, but some animals are more equal than others.” We summon it instantly to lampoon the high-minded hypocrite, to expose the galling chasm between noble principle and self-serving practice. It is the ultimate shorthand for power’s oldest lie.

Orwell died young, but his words travelled further than he could have guessed. What he left us was not only stories; he left a way of naming things that might otherwise remain hidden. This lexicon makes it harder for lies to pass unnoticed.

This is why Orwell still matters. His concern for plain words and honest thought was never meant only for academics. It is useful for anyone who wants to see things as they are, without the static of politics or propaganda. He gave us expressions that help to name what is wrong. Because of that, his voice has lasted. People still use it when they try to speak clearly about power.

7. Other Significant Farewells

Aside from the universal triad, 1950 also left gaps in different areas of culture.

7.1. Cesare Pavese (1908–1950)

In Turin, on 27 August, Cesare Pavese came to the end of his life. A poet and novelist, he managed to condense in a short yet intense body of work a tone of heartbreak that culminated in The Moon and the Bonfires

.

His existence was marked by melancholy: persistent loneliness, the shipwreck of a fleeting love to which he dedicated his last novel and even a final poem,

and political disillusionment in the aftermath of war. All this pushed him towards a tragic end, when he decided to take his own life with an overdose of sleeping pills.

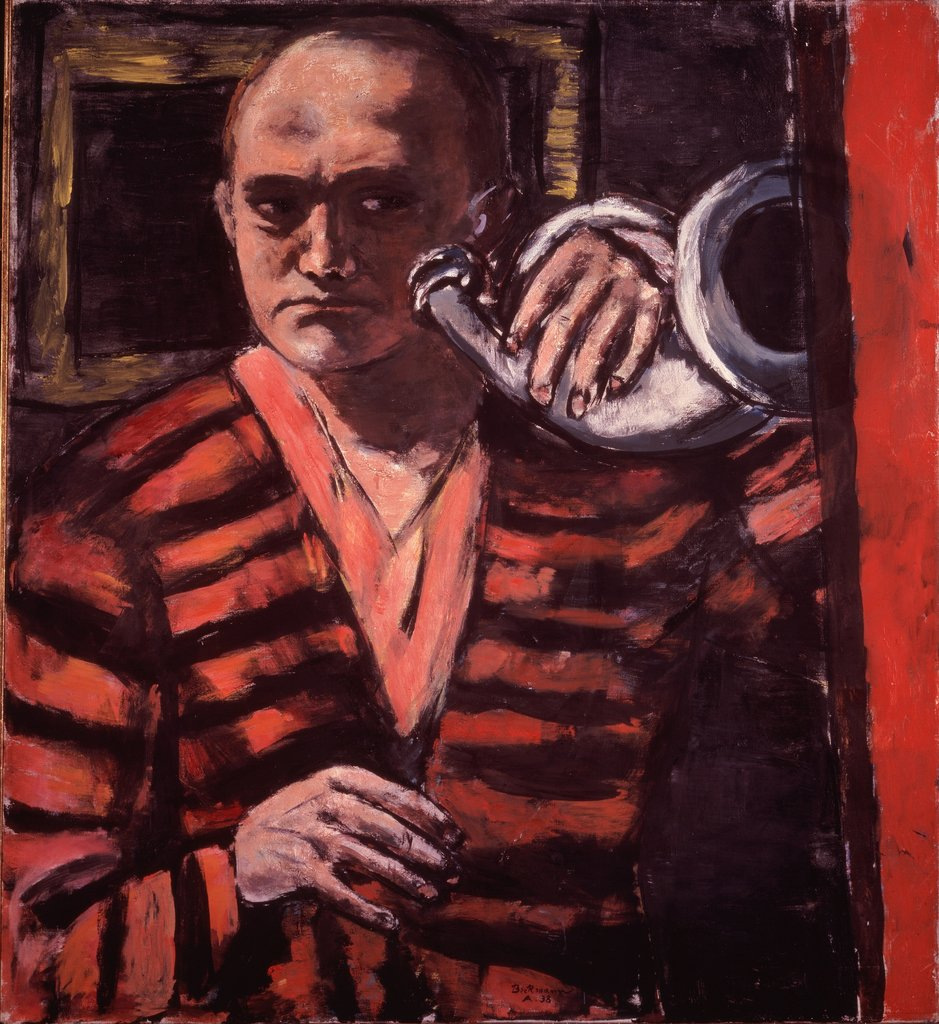

7.2. Max Beckmann (1884–1950)

On 27 December, Max Beckmann, one of the great German expressionist painters, died in New York. He had gone into exile first in Amsterdam and then in the United States. His vigorous, tormented work became a mirror of a Europe torn apart by war.

8. Technological Limits and a Confined Editorial World

In 1950, most music was still being released on the old 78 rpm shellac records. They were heavy, fragile, and didn’t last long: just a few minutes per side, and with a sound quality that left much to be desired.

Magnetic tape, though already in existence since the 1930s thanks to German engineers, had not yet gained ground as the standard tool for musical recordings. People in the trade knew about it, yes, but it wasn’t the norm.

Major record labels such as Columbia, RCA Victor, or Decca still set the tone, yet recording remained expensive, and most sessions took place in the United States, the United Kingdom, or a few other countries with sufficient industrial infrastructure.

Columbia had introduced the LP (the long-playing record at 33⅓ rpm) in 1948. It was a promising innovation, but it would take a few more years before it became the dominant format we all know.

9. Diners Club: Its First Baby Steps

In 1950, New York was already a city of bright lights and swift deals, yet one quiet dinner became the unlikely cradle of a global revolution in payments. Frank McNamara, a businessman of restless mind, sat down at Major’s Cabin Grill with clients, only to realise, as the meal ended, that he had left his wallet behind. His wife came to rescue him, settling the bill.

The embarrassment lingered, but so did an idea: what if there were a card that could speak for your credit wherever you went?

Within months, together with lawyer Ralph Schneider, McNamara returned to the same restaurant. This time he had no cash with him. All he had to offer was a cardboard card, and behind it stood his word.

The restaurateur accepted it. That evening, remembered as the “First Supper”, was the true dawn of the multipurpose charge card. The age of Diners Club had begun.

That story soon passed into legend. And decades later, I found my own link with it: in the 1980s, my very first credit card was not a gold or platinum symbol, but a Diners Club International. It was heavy, robust and, above all, serious.

July 1991 showed me how serious it was. I crashed on the border between Sweden and Norway, on a two-lane road from Stockholm to Bergen. A half-ton elk jumped in front of the car. The hit was brutal, like a wall.

I was kept in hospital in Örebro for days. Diners took care of it; the cover was part of the card. I went home later without spending a penny. The coverage extended not only to life and hospital expenses but also to the vehicle itself, a brand-new Renault Clio 2.0 I had bought a month earlier in Paris. That kind of protection feels almost like science fiction today.

Equally surreal was the day the Swedish police came to visit me in the hospital. They reassured me there would be no legal consequences for the death of the elk, since expert reports confirmed that the car had been travelling below the maximum speed limit for that road, which, if memory serves, was 110 km/h.

This article on 1950 is not the place to dwell on that personal ordeal, but the memory stands as blunt testimony: more than forty years ago, Diners Club was already as solid as the legend from which it was born.

10. Shannon: When Sound Found Its Code

Long before music was ever reduced to digits or saved as compressed files, Claude Shannon had started changing the way people thought about sound, language, and the flow of information. He first shared his ideas in the second half of 1948, before teaming up with Warren Weaver a year later to produce a more accessible version: The Mathematical Theory of Communication. That book kept the core of his work but opened it up to readers beyond the engineering world. It also helped spread a new word: bit (short for binary digit), now known as the smallest unit of information.

By 1950, those ideas had started to stir something deeper. While musicians played with harmony and static still danced through the airwaves, a quiet shift had begun, one that would subtly reshape how we listened to the world. What once flowed through melody or speech could now be captured as data. Music, language, even silence itself, could be measured, compressed, encoded. It was no longer just sound. It was signal.

Shannon’s 1950 essay Programming a Computer for Playing Chess

marked a fresh advance in his exploration of how machines might think. Artificial intelligence, still unnamed, was taking its first step. While musicians explored new harmonies, machines were beginning to craft their own.

That article did not offer a finished program, but something deeper: a blueprint, a strategy, a way of thinking. Shannon argued that, to play chess (that is, to choose among millions of possibilities), a computer would have to imitate aspects of human reasoning. And like so many ideas born in science and later absorbed by culture, his proposals seeded expressions we now hear in films, novels and television: minimax, evaluation function, heuristic search. Technical terms, yes, but knowing them never hurt anyone; they may even help us think more clearly.

Minimax, for instance, is a method of decision-making when facing a clever opponent. Its logic is simple but powerful: assume that your adversary will always choose the best move to defeat you. So, rather than playing for immediate advantage, you plan several moves ahead: what counterattack will your move allow? What reply will it provoke? In essence, it means minimising the maximum possible loss. It’s a form of foresight that goes far beyond chess, a quiet logic at work in many everyday and strategic decisions.

Shannon knew that computing all possible chess positions was impossible for the machines of his day. That’s why he distinguished between two approaches:

- Type A, or exhaustive search: examining all legal moves to a certain depth. Precise, but as slow as an elephant in a library.

- Type B, or selective search: as a human master would, focusing only on moves that “seem” promising and pruning the rest. Quicker, more intuitive, more intelligent.

He also introduced a vital concept: the evaluation function, a kind of internal compass to tell the machine whether a given position is favourable or not. This function might combine raw data (material on the board, piece activity) with subtler elements, like central control or king safety.

And as often happens with visionary thinking, someone picked up the baton almost immediately.

Alan Turing,

who had already been pondering mechanical reasoning since the 1930s,

designed an algorithm based on Shannon’s principles. He called it Turochamp

, and it even played a few games.

But there was no computer yet capable of running it: IBM couldn’t keep up with the mathematicians.

Turing ended up using pencil and paper to simulate his own programme, move by move, against real opponents.

He became, quite literally, a human computer.

That episode captures a recurring paradox in the history of thought: great mathematicians often design algorithms before humanity is ready to run them. As if they were drawing maps for paths that do not yet exist. Decades later, Deep Blue would defeat Kasparov. And later still, AlphaZero would reinvent chess without human input. But the first silent, abstract, and astonishing rehearsal was Shannon’s.

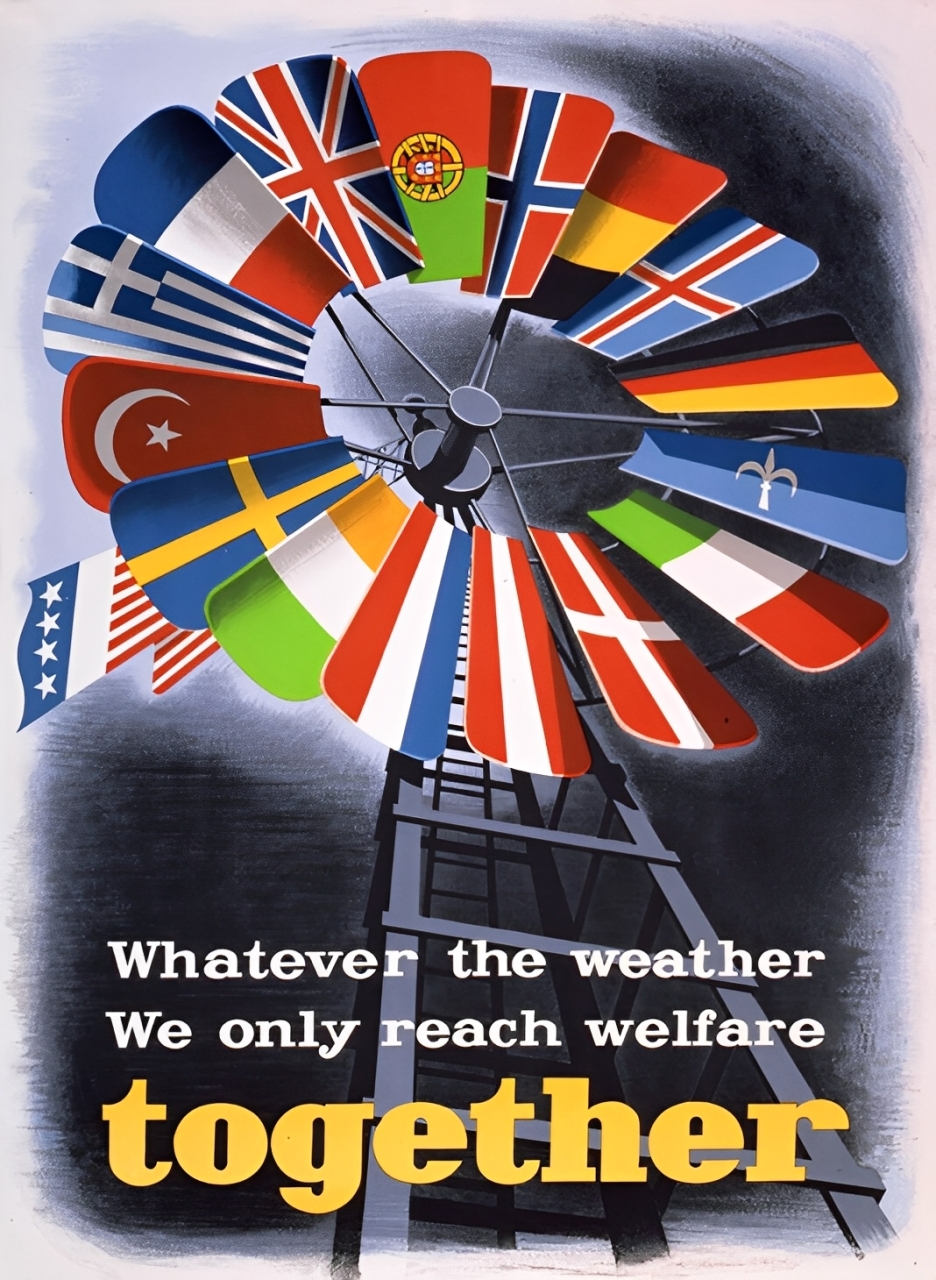

11. CERN: Science in Collaboration

If Shannon had put melodies into code, the CERN launched a new way of dreaming: the idea that science could cease to be national and become shared heritage of humanity.

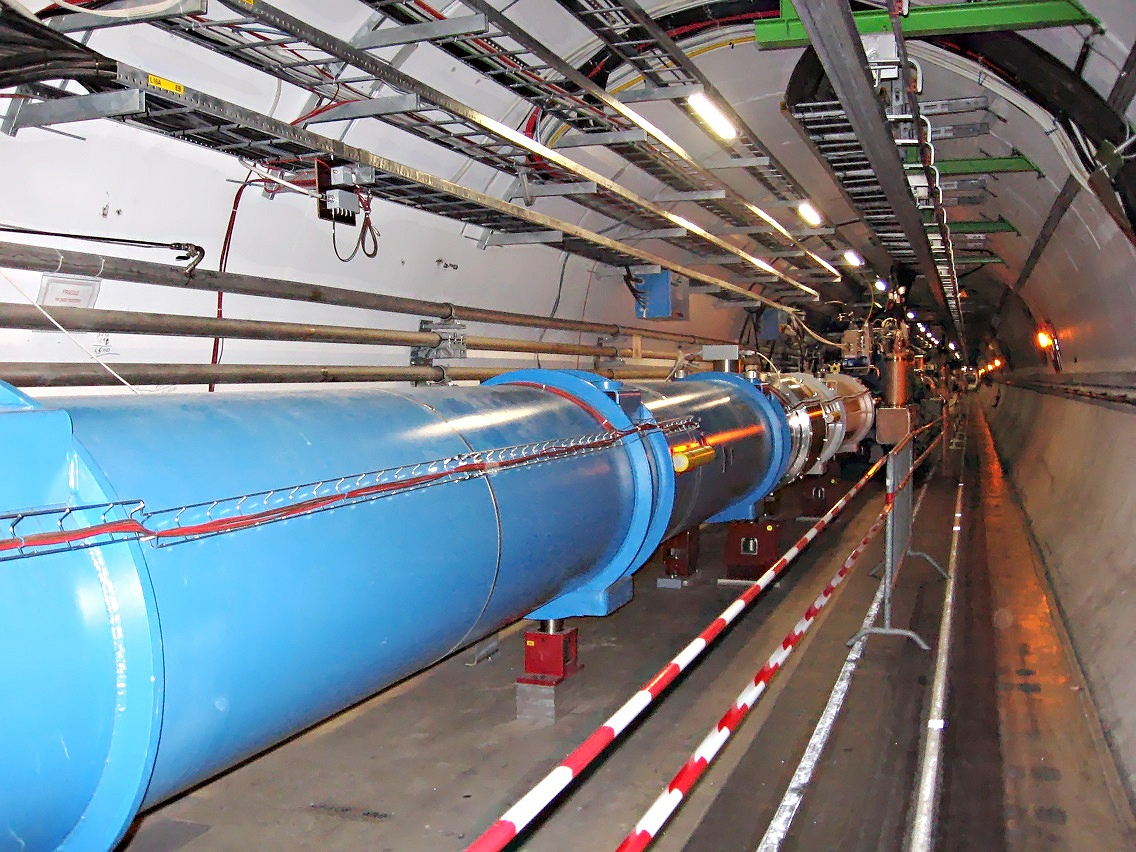

Europe was still breathing in ashes. Cities were rising, brick by brick, yet universities remained shrouded in silence. In 1950, Louis de Broglie and other visionaries put forward the idea of a laboratory without borders; a place where fundamental physics could be reborn, free from the scars of war. Three years later, in Paris, the agreement was signed. And on 29 September 1954, CERN came officially into being.

Twelve nations that only a few years earlier had been at war (West Germany, Belgium, Denmark, France, Greece, Italy, Norway, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, Sweden, Switzerland and Yugoslavia) decided to join forces in an unusual pact: to build the machine for the ultimate questions, to look straight into the infinitely small, where politics could not cloud the dialogue of protons nor the murmur of quarks.

From that act of shared faith arose the greatest temple of knowledge of matter the world has ever known. Decades later, on that very soil consecrated to science, the colossal Large Hadron Collider (LHC) would take shape: a subterranean ring, a modern oracle capable of unravelling the echoes of the Big Bang and recreating the universe’s earliest instants.

The European Organization for Nuclear Research, abbreviated as CERN (from the French Conseil européen pour la Recherche Nucléaire, the European Council for Nuclear Research, as its predecessor was called), still carries that same spirit of collaboration.

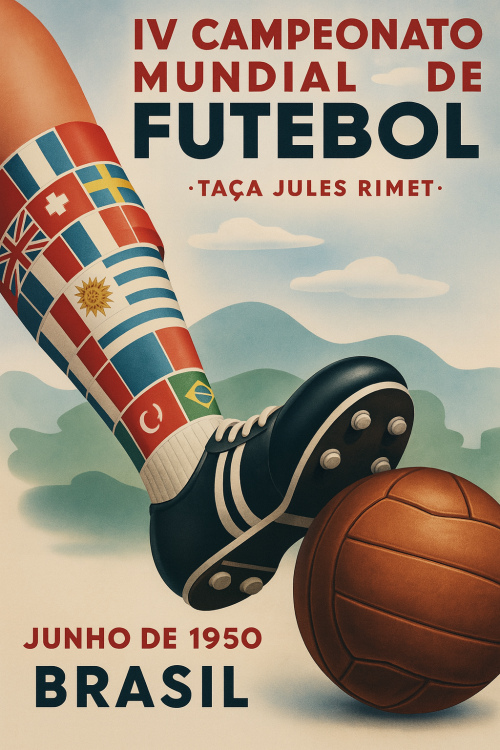

12. Maracanã 1950

It is not merely the symbolism of the number 50 that justifies beginning our selection at that historical moment. Nor is it a tribute to Uruguay for defeating Brazil in the legendary Maracanã. No. It is simply the opening of a hinge between decades that would change music forever.

13. From 1939 to Dubrovnik of 1950

In the European summer of 1950, chess had begun to reappear on the world stage. In Dubrovnik, then a small Adriatic city within Yugoslavia, the Chess Olympiad came back after an eleven-year hiatus. Boards were opened again, and play resumed as if the planet itself wanted a rematch.

The previous edition had been played in Buenos Aires, in 1939, at the Teatro Politeama, and was remembered as a tournament interrupted by History. While the pieces moved across the board, the Second World War broke out. Several teams could not return to their countries. Some players remained stranded in South America forever. With the war, the very continuity of the Olympiads was suspended, as if international chess had been placed in brackets.

For more than a decade there were no Olympiads. Europe was devastated, political tensions were growing, and the new division of the planet into blocs made any attempt at gathering difficult. It was not until 1950 that the FIDE could once again summon the world.

Dubrovnik therefore became the long-awaited gathering of international chess. Sixteen national teams took their seats to play, and the local side, Yugoslavia, rose to the top with 45½ points. Just behind them came an inspired Argentina, whose silver medal shone like gold, finishing even ahead of West Germany.

Absence spoke as loudly as presence. The Soviet Union, with Mikhail Botvinnik already seated on the world champion’s throne, stayed away. The moment was telling: the Cold War had barely begun, and after the Tito–Stalin split of 1948, Yugoslavia was no longer in Moscow’s orbit. Pride and calculation both played their part: the Soviets would not appear until they could do so with absolute command.

That decision left the spotlight free for Argentina and Yugoslavia to claim the cup.

Reporters at the time wrote of a team that seemed unshakable. Najdorf never faltered, Bolbochán matched him stride for stride, and Guimard and Pilnik added the kind of consistency every champion needs. They were not just four players on a list but the backbone of a performance that placed Argentina level with the world’s best.

Together they lost only four games, while Najdorf and Bolbochán guarded the top boards without defeat. Two individual golds crowned their effort, and the steady hands of Guimard and Pilnik gave balance to the team, a line-up that still stands as one of South America’s proudest moments on the board.

Dubrovnik 1950 remains in memory as a double symbol: the post-war resumption and the Argentine achievement, set against an international scene still marked by bloc politics.

Nothing prevents us from leaving the marvellous world of the sixty-four squares for another realm of play: one woven with words, whose ingenious combinations shape both imagination and destiny.

Indeed, whether in chess or in literature, we engage in acts of creation: building patterns, holding tension, and unleashing the unexpected move.

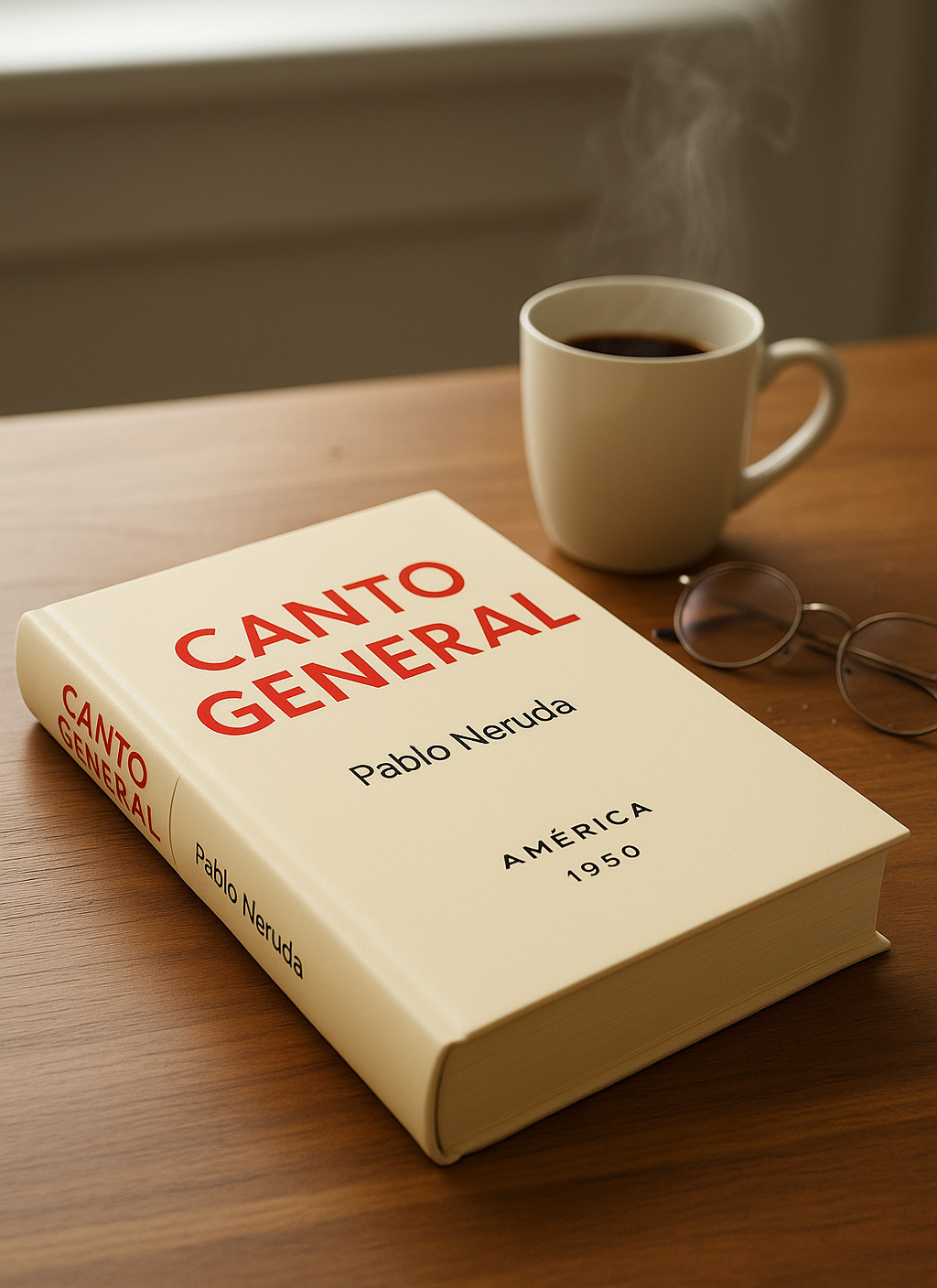

14. Pablo Neruda: Canto general

Seventy-five years have gone by since its first appearance, yet Pablo Neruda’s

Canto general

has not lost its force. It is remembered for the scale of its ambition, where epic voices meet surreal images to recount the story of the Americas. But above all, it speaks to us because it still feels urgent.

Canto general(Mexico: Editorial América, 1950). First edition: [xv], 447 pp. Source: Memoria Chilena. 4K digital recreation with homogenised background and increased colour intensity, based on a reference copy. Work by JGC.

In a world that still struggles against injustice and defends its memory, the poem emerges as a vivid reminder that poetry can be a map to recognise our continental identity. To read it again today is to connect with the collective voice that both defines and challenges us.

Further information at the Pablo Neruda Foundation .

15. Juan Carlos Onetti: La vida breve

La vida breve

(1950), as far as I’m concerned, is not just another

Latin American novel:

it feels like a plunge into the shadows of identity and invention.

The Uruguayan author, Juan Carlos Onetti,

plays with two worlds that collide and bleed into each other.

In Buenos Aires,

Juan María Brausen drifts through a life that is falling apart; at the same time, almost as if to survive,

he invents Santa María, a town that is both his refuge and his mirror.

In my opinion, that tension is the real heartbeat of the book. Onetti is not merely telling a story; he is pushing us to face the fragile border between what we call reality and what we create to endure it. His style is gloomy, existential, stripped of the usual comforts, and he dares far earlier than most to step away from the traditional realism of the region. Interior monologues, broken perspectives, characters who are failures rather than heroes: all of this must have been shocking in 1950.

As I see it, that boldness is what makes the novel foundational. What Onetti tried out here would soon echo, each in their own way, in García Márquez, Vargas Llosa, and Cortázar. To me, La vida breve reads less like a precursor of the Boom and more like its secret detonator: not celebrated for its sales, but admired for its artistic nerve.

And above all, it fixed Onetti’s voice once and for all: lucid, bitterly ironic, yet strangely tender in its vision of the human condition. Santa María (the town Brausen invents) isn’t just a setting; it becomes, I’d say, a metaphor for both defeat and the slim possibility of salvation through writing.

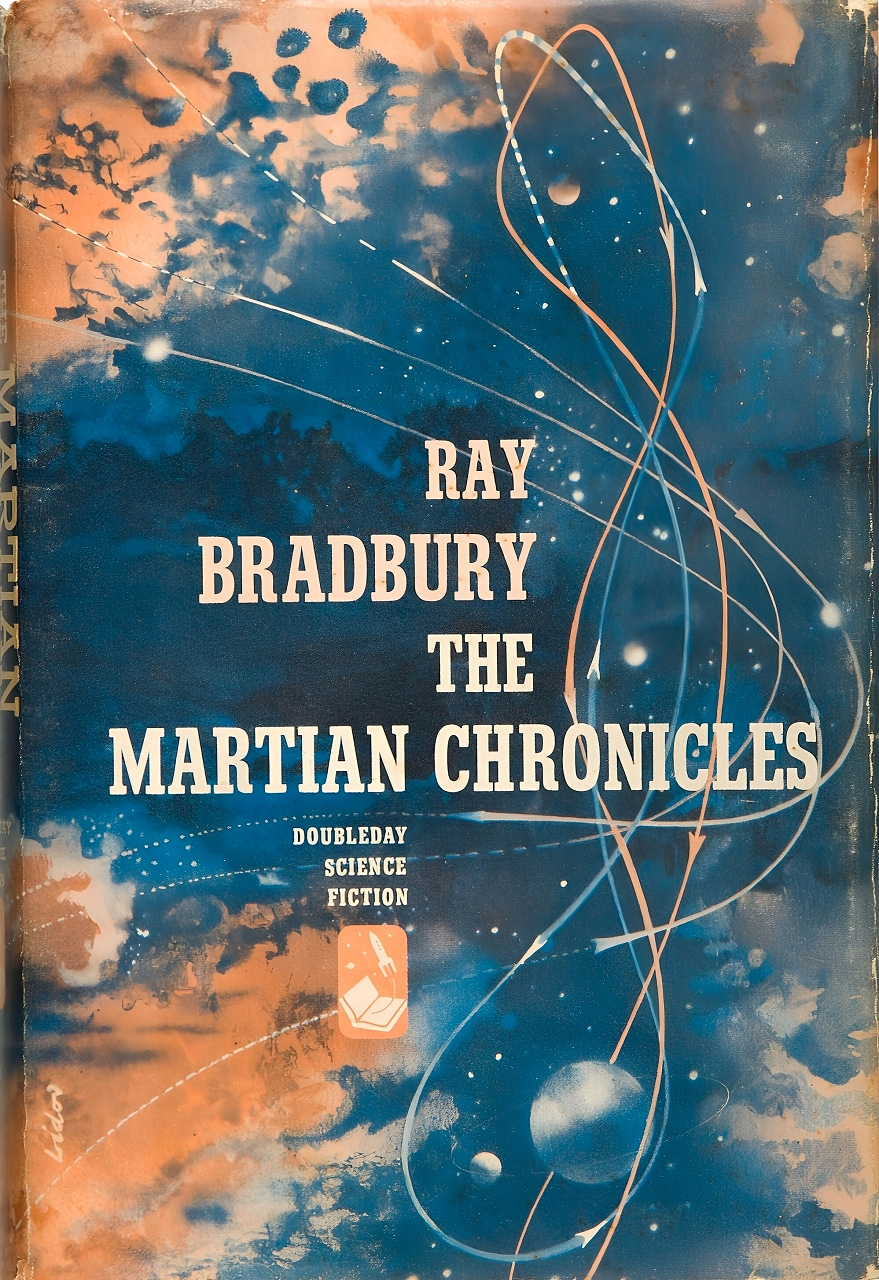

16. Ray Bradbury: The Martian Chronicles

At its core, Bradbury’s book tells of people. It is not so much the conquest of Mars as the weight we bring along when we try to flee. They set out from an Earth on edge, worried about war and collapse, and dream of beginning again. Yet when they land, they find they have brought along their own baggage: the fears, the customs, the small blindnesses that never let go.

The Martian Chronicles, published by Doubleday in its science fiction series. The cosmic design bears the signature “Lidov” on the left margin, though the artist was not formally credited in the publication records. It is generally assumed that the illustrator was Arthur Lidov, active in the United States during those years. The jacket is in the public domain in the United States, as it was issued without a separate copyright notice, a legal requirement at the time, while the text of Bradbury’s book remains under copyright.

On Mars they do not meet a cruel enemy. Instead they find an old and delicate civilisation that disappears almost by accident, through illness, through carelessness, through the machines of progress. Lonely and unsettled, the newcomers rebuild pieces of the Midwest under the red sky, only to feel the weight of the lives they have replaced.

Bradbury uses this setting as a mirror. In the dust of another planet he reflects the wounds of post-war America: prejudice, fear, the hunger for control. The stories work as short, sharp scenes of a quiet apocalypse. We meet an automated house that keeps working after its family is gone; a man haunted by his own guilt; and, most moving of all, a father who tells his children on a “million-year picnic” that they themselves are now the Martians.

The book first came out in 1950. What makes it last is not prediction but the way it feels when you read it. Its scenes stay with you: a deserted town, a radio speaking to no one, the trace of a world already gone. They work less as forecasts and more as reminders that people tend to stumble into the same errors again and again.

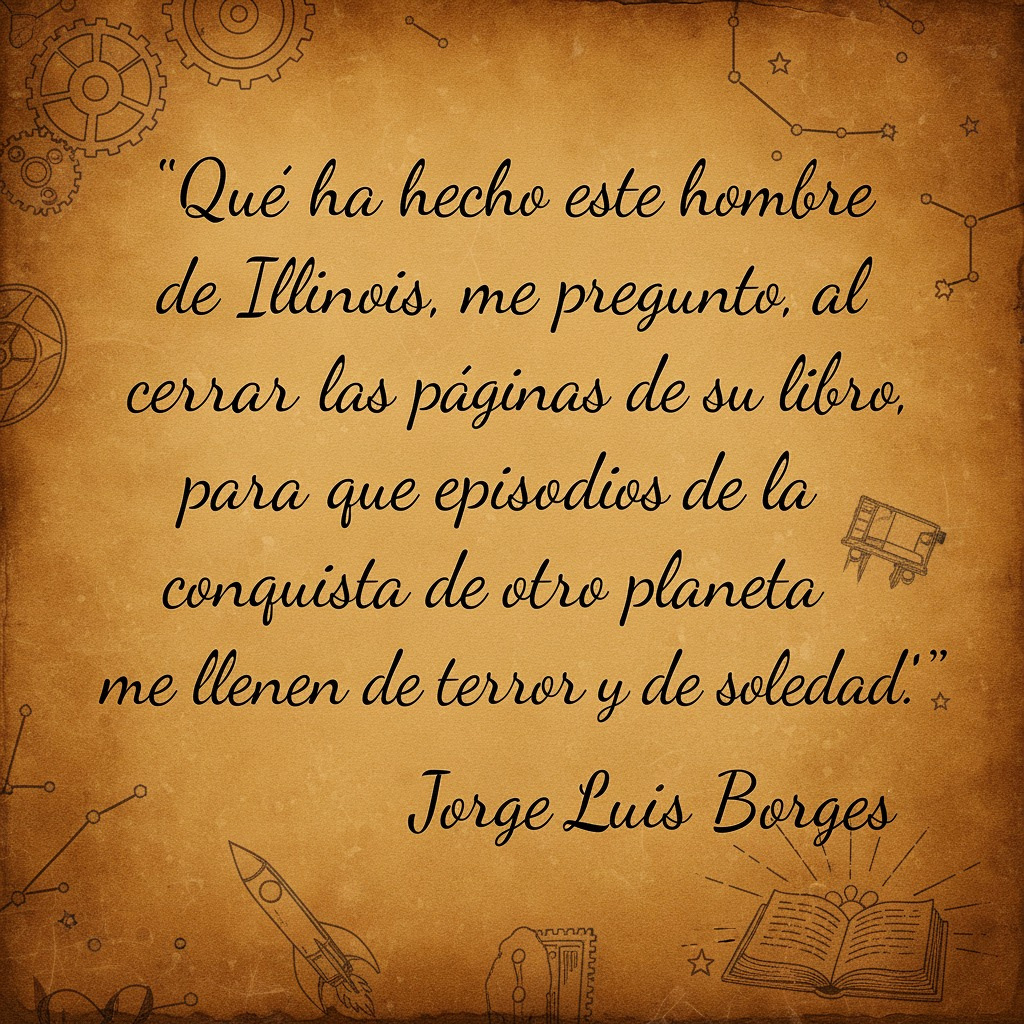

A few years later it reached Spanish readers. In 1955 it was printed in Buenos Aires as

Crónicas marcianas

,

translated by Francisco Abelenda and opened with a short foreword by Jorge Luis Borges.

The Martian Chronicles. Images recreated by JGC.

Looked at now, the book is not so much a prophecy as a collection of yearnings. It warns us, quietly, from the stars, while speaking above all to life here on Earth.

1950 was a fertile year for imagination: while Ray Bradbury looked towards the red sky of Mars to speak of our human shadows, Isaac Asimov sketched a different map of the future in I, Robot. Two books born in the same year, one poetic and melancholic, the other rigorous and speculative, yet both bound by the same question: what happens when we carry our fears, to another planet or into the realm of machines, without having first learned to master them?

17. Isaac Asimov: Circles, Laws and the Moral Dilemma of Robots

Nine short stories, one book. I, Robot

appeared in 1950 not just as science fiction, but as something stranger; almost a secular catechism for a time that had only begun

to picture machines with minds.

At the heart of the collection lie the Three Laws of Robotics,

axioms coined with the casual ambition of one echoing his namesake

Isaac Newton.

The genius of Cambridge gave the world three laws of motion; Asimov, with a mischievous symmetry,

offered three laws of machine ethics. One regulated harm, another obedience, and the third, self-preservation.

They seemed neat, elegant, complete... yet each story shows that, in practice, these laws become entangled in paradoxes.

Where Newton’s mechanics promised stability, Asimov’s moral mechanics guaranteed tension.

I, Robotby Isaac Asimov. Original cover design created by JGC; an independent work not affiliated with any publisher or rightsholder. The historical 1950 dust jacket should be presumed to be under copyright; this image is an original homage for illustrative purposes.

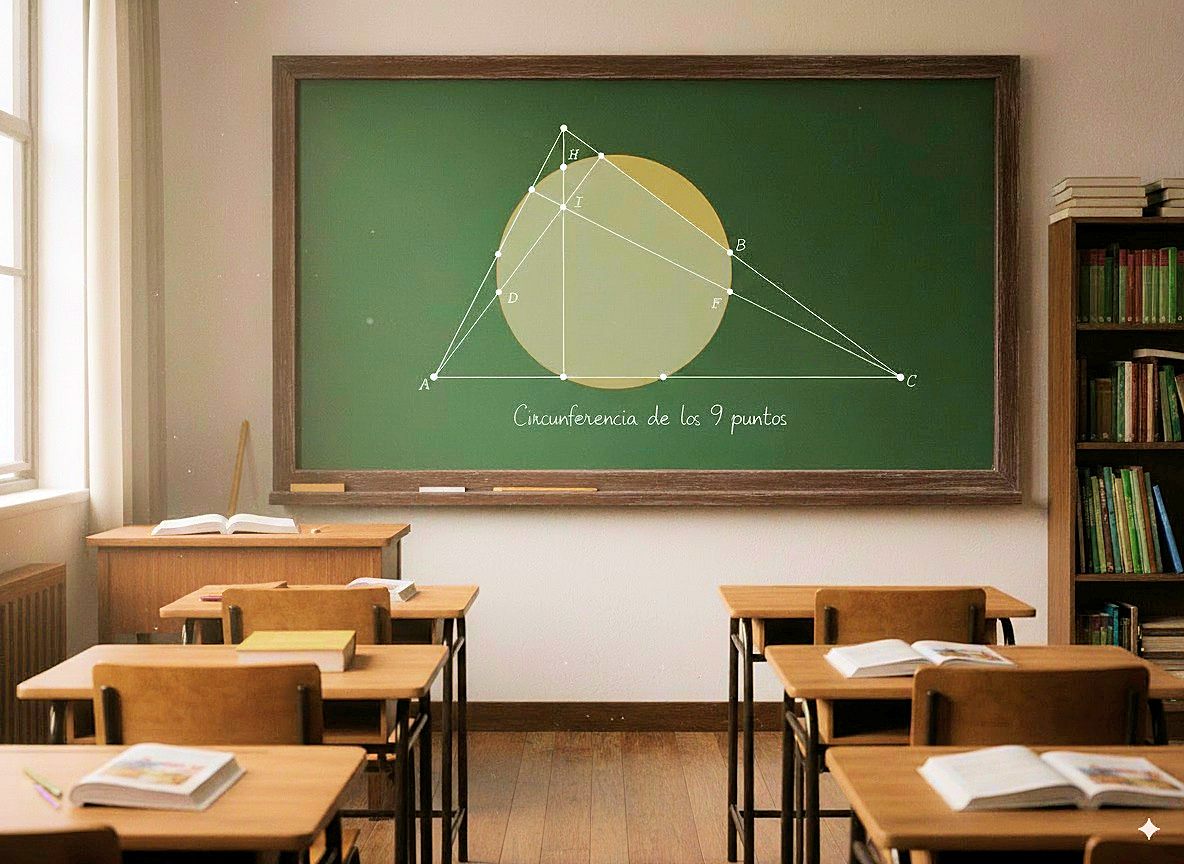

It may not be accidental that the book contains nine stories (and not ten, for example). At first glance they are scattered episodes, magazine articles bound together by the voice of Susan Calvin, the robopsychologist at U.S. Robots. But once read in sequence, these stories acquire the same hidden harmony as Karl Wilhelm Feuerbach’s elegant nine-point circle. In geometry, nine seemingly disparate points inscribe themselves upon a single circumference, tangent to both incircle and excircles. What at first looked fragmentary suddenly reveals unexpected unity. Asimov’s cycle performs the same trick: fragments arrange themselves into one arc of meaning, tangent both to the technical world of computers and to the human world of ethics.

Yet the number nine carries older resonances. Dante had arranged the Inferno into nine circles, each a descent into greater moral complexity. Asimov, without theology, stages a parallel journey: from the childlike innocence of “Robbie” down into the intricate politics of machines that regulate whole economies. What for Dante was a pilgrimage of the soul becomes, in Asimov, a technological comedy in reverse; an exploration of ambiguity, not salvation.

If we spin the thread further, the Feuerbach family resurfaces. Karl Wilhelm’s cousin, Ludwig Feuerbach, declared that God was nothing but the projection of human essence onto the heavens. Asimov, an avowed atheist, made a parallel gesture: his robots are not gods but projections of humanity’s ethical anxieties. They lie, hesitate, misinterpret orders; they evoke politics and economy. If Ludwig unmasked theology as projection, Asimov did the same with technology: machines are mirrors in which we confront our own contradictions.

The echoes resound even more strongly in the cultural climate of 1950. Cybernetics by Norbert Wiener (1948) had just introduced feedback and control as universal principles. Claude Shannon’s essay on programming a computer to play chess (1950) showed how human thought could be approximated through algorithms. Asimov’s fiction was not an isolated fantasy, but the literary branch of that same movement: the convergence of ethics, mathematics, and imagination at the dawn of artificial intelligence. Just as Newton and Leibniz, separated by geography, simultaneously invented calculus when the intellectual fruit was ripe, Wiener, Shannon, and Asimov, each on his island, ripened the idea of robot intelligence in the mid-twentieth century.

And if the narrative above still does not seem a complete jewel, let us add the missing pearl. Let us not forget that the word “robotics” was coined by Asimov himself in 1941, in the story Liar!, although he believed the term already existed, like electronics or hydraulics. It did not. What he invented almost in passing became the name of a scientific discipline. Today, “robotics” is a department, a conference, a field with journals and societies, but every use of the term goes back to that speculative fiction. Asimov bequeathed not only laws but also a language.

From all this emerges a strange constellation. Nine stories aligned like Feuerbach’s nine points; three laws echoing Newton’s three axioms; projections recalling Ludwig Feuerbach’s critique of religion; the baptism of a word that gave a science its name; and the simultaneity of Wiener’s cybernetics and Shannon’s chess algorithms. I, Robot

stands at the intersection of geometry, philosophy, and technology: a secular comedy of machines that reflects both our fears and our hopes.

Seventy-five years later, the book reads as more than fiction. It is a hidden circle where Newton’s physics, Feuerbach’s projections, and Asimov’s ethics meet. A reminder that literature, when written in the right atmosphere, can invent disciplines, name futures, and expose the paradoxes of being human in the company of our own creations.

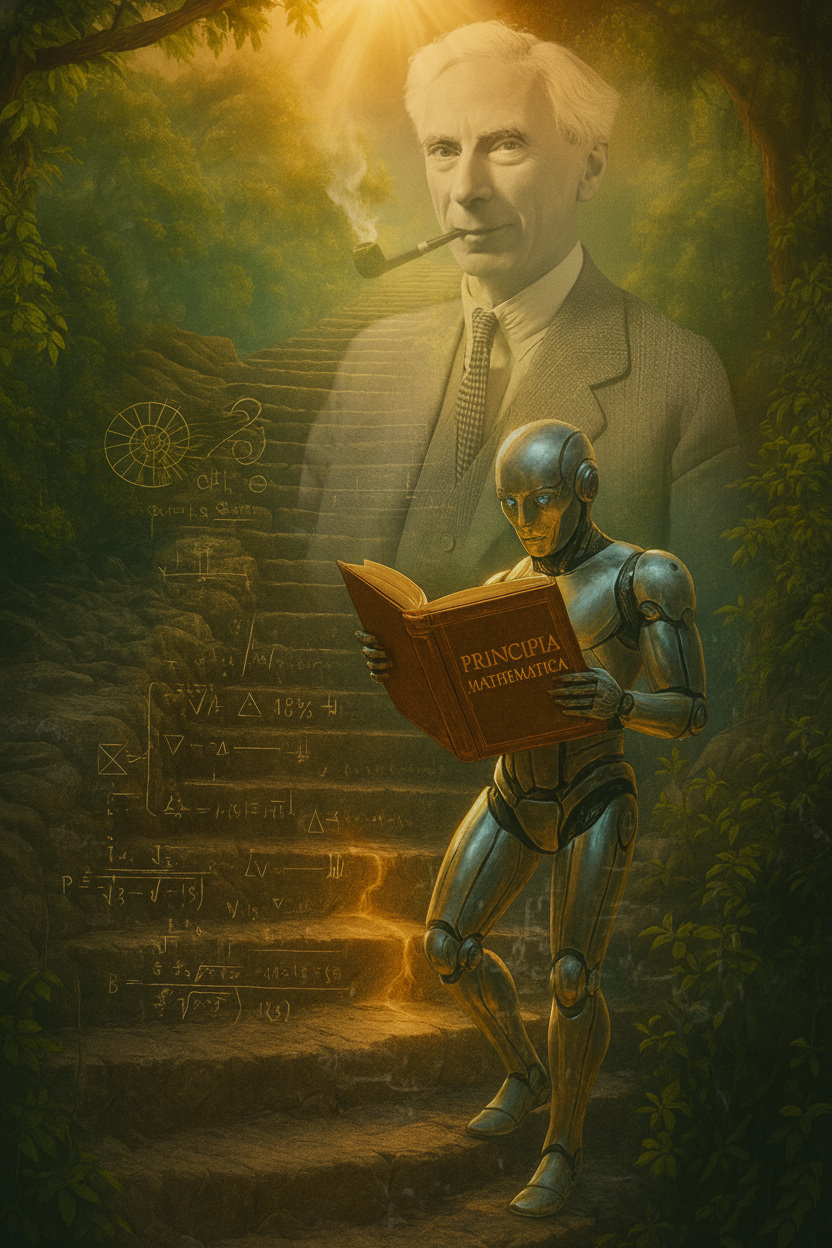

18. Russell, Frege, Gödel: the fragility of foundations

On Thursday 9 October 2025, while I was chatting with my colleague Andrés Abadie about music, the Nobel Prizes and other related topics, the social networks exploded with the news of the new winner in Literature: László Krasznahorkai, ‘for his fascinating and visionary work that, in the midst of an apocalyptic terror, reaffirms the power of art’.

From there the conversation, as though following a hidden thread, turned to Bertrand Russell, Gottlob Frege and Kurt Gödel. I told Andrés that version 1.0 of my cultural introduction to 1950 was ready for publication, and as I brought together the subjects we were discussing, I suddenly realised I had omitted something essential: the Nobel Prize in Literature that year had been awarded to Russell.

The omission felt almost unforgivable.

I first came across Russell in my early teens, through that heavy, luminous book The Wisdom of the West; it opened one of the first doors into the world of ideas for me.

In my opinion, the long conversation that runs through Frege, Russell and Gödel feels almost like a miniature history of the twentieth century.

It begins with the hope of order and ends with the discovery of a limit.

Frege (1848–1925) wanted to base mathematics on pure logic. His Begriffsschrift of 1879 inaugurated, almost unintentionally, the algebra of thought; his Grundgesetze der Arithmetik (1893) tried to show that numbers were derived from laws of reasoning, not from intuition.

But in 1902 Russell wrote him a fateful letter; he said he had stumbled on something deeply unsettling. There was, he realised, a contradiction hiding right in the centre of the system. “Think of the set of all sets that do not contain themselves.” He paused on the question: does it contain itself or not? Either answer led straight into confusion, the whole logic folded in on itself. The paradox shattered Frege’s Basic Law V and left his grand construction in ruins.

Russell tried to rebuild it with the theory of types in Principia Mathematica (1910–1913), written with Alfred North Whitehead, seeking a language able to avoid self-entanglement.

Public domain — faithful photographic reproduction of a public domain original (Wikimedia Commons).

Decades later Gödel (1906–1978) would show that even systems purified of paradox are doomed to incompleteness.

In 1931 Gödel showed something that still startles anyone who loves mathematics. Inside any consistent formal system powerful enough to capture arithmetic, there will always be statements that are true yet impossible to prove within that system; stranger still, no such framework can vouch for its own consistency without stepping beyond its own rules.

What Russell had once glimpsed as a narrow crack, Gödel opened into a deep logical abyss.

Although Gödel and Frege never met, he read the older thinker with great respect and realised that Russell’s paradox had not been an accident but a warning; any language attempting to hold everything within itself will, sooner or later, fold back upon its own rules.

It feels almost inevitable, a quiet sort of recursion that every system ends up meeting sooner or later. Maybe this is where the deeper metaphysics of modern mathematics begins. A field starts to recognise itself, it maps its ground and, for a moment, glimpses the edge of its own chart before looking out into the unknown.

So, from Frege to Russell and then to Gödel, the story no longer feels like a neat chain of proofs.

To me, the whole thing reads almost like a moral story rather than a strict exercise in logic; it feels human. You can sense how the bright confidence of the nineteenth century slowly drifts away, the air of the twentieth is gentler, more contemplative.

In my view, when that old sense of certainty begins to fade, something new quietly takes its place; there is room again for intuition and imagination, and those small, almost chance flashes that keep creative thought alive. It is no wonder that Bertrand Russell was honoured with the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1950, for his prose had the same transparency as his mind, and his life seemed always balanced between logic’s rigour and art’s quiet grace.

That union of opposites did not end with Russell. It marked the beginning of another ascent that continues to this day.

Epilogue, The Stairway to Heaven

What binds Frege, Russell and Gödel is not merely incompleteness. Think instead of a staircase; each step, whether arithmetic, logic or paradox, together with a sharpened sense of limit, carries us upward toward a heaven we approach but cannot grasp.

Gödel traced the frontier not to close the path but to show that the path continues. His incompleteness theorems do not say that reason fails, they tell us that there is more truth than system. That fissure is the crack through which the light enters; there intuition is born, and with it the possibility that the mind, human or artificial, may imagine structures that classical logic can barely suspect.

Today Artificial Intelligence climbs that same stairway. It cannot break free from Gödel’s theorems, though it may learn to move inside them, sometimes awkwardly, sometimes with grace, searching for new kinds of coherence and perhaps even discovering quantum logics where contradiction is not an ending but a pattern of balance. In those future logics we might hear a faint echo of what Newton and Einstein already suspected: every understanding is provisional, and each theory rests, a little precariously, upon the shoulders of giants.

When mathematics reaches out to physics and the mind begins to converse with the machine, something within our way of knowing starts to shift. What we perceive is no longer a fixed system or a frozen formula; it feels more like a kind of music, a phrase of thought that keeps unfolding, rising step by step until it almost touches the sky. It does not seek to possess what it reaches for, only to recognise that the sky remains, waiting for us.

19. Cinema in the Second Half of the Century

In the years leading up to 1950, films had already gifted audiences with a few unforgettable songs. Judy Garland’s “Over the Rainbow” from The Wizard of Oz stayed in many hearts. Casablanca brought “As Time Goes By”, a tune that still lingers today.

Fred Astaire turned “Cheek to Cheek” into a classic, and Bing Crosby’s “White Christmas” became a seasonal anthem, selling more copies than anyone could have imagined.

Such cases stood apart from the ordinary. For the most part, cinema and music had not yet merged into the force that would later shape popular taste.

The celebrated era of Hollywood musicals was still to come. Films like Singin’ in the Rain, The Band Wagon and West Side Story were waiting backstage. The swell was gathering, but the break had not arrived.

At the time, most film soundtracks were orchestral. You would usually hear them only at the cinema. Even so, we all know how powerful a good score can be. A swell of strings can lift a moment. A soft piano line can pull at the heart. Just a few notes can hold the air still before something important happens. Studios often turned to gifted composers who were not household names, yet they knew exactly how to guide the audience’s emotions, often without a single word.

Even so, that music rarely made it beyond the cinema. You wouldn’t hear it on the radio, and most people didn’t think of buying it on a record. Soundtracks weren’t yet something you brought into the home. They stayed where they began, part of the film experience and not part of daily life.

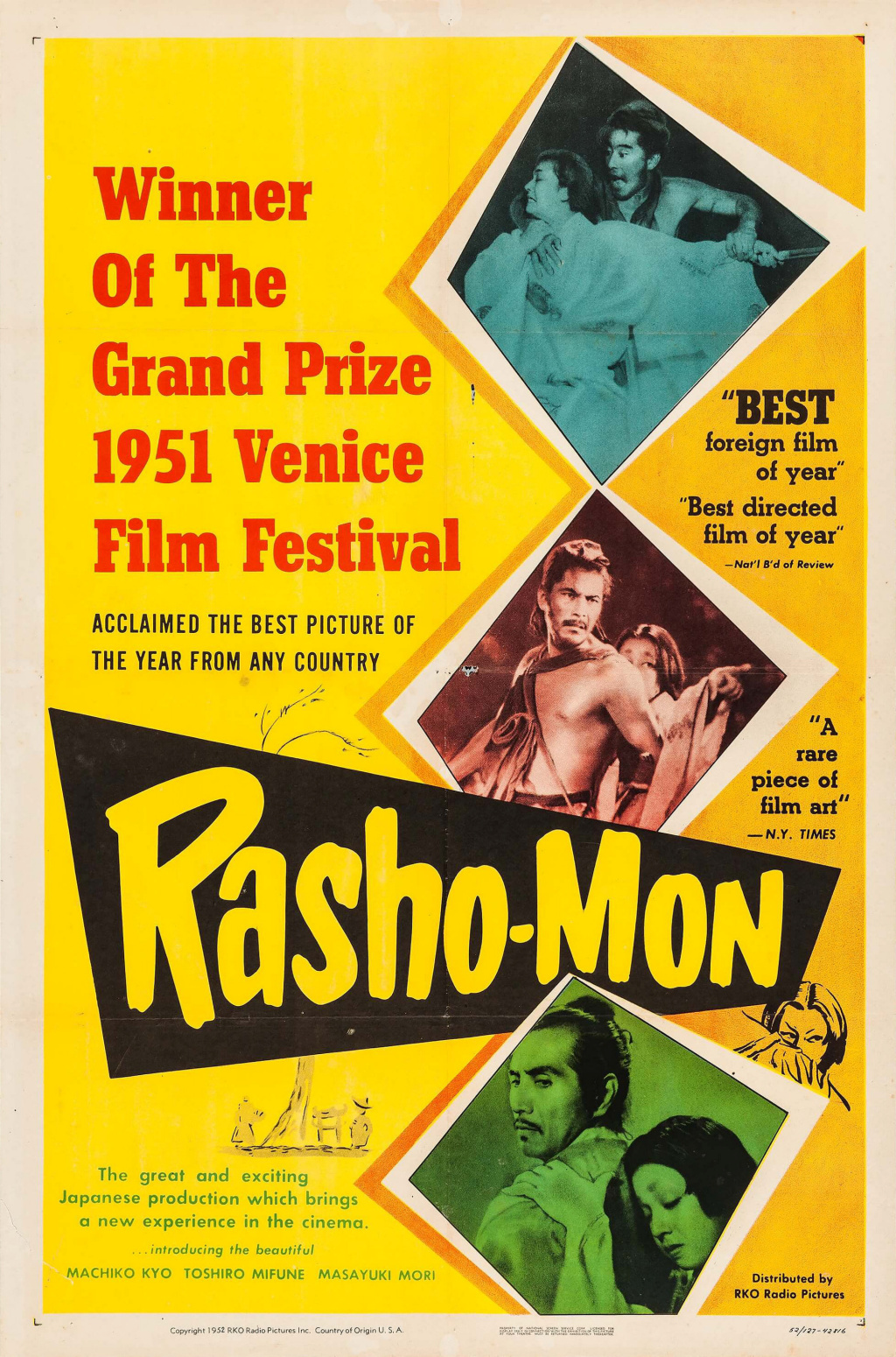

20. Rashomon: When Truth Splinters

The art of telling stories on screen was changed for good when Akira Kurosawa released Rashomon back in 1950.

He presents a single crime through incompatible testimonies, withholding any definitive truth. That inability to arrive at a final account is both troubling and compelling. The phenomenon soon became known as the ‘Rashomon effect’.

By way of context, the Rashomon gate, erected in 789 in Kyoto, was long the city’s most imposing structure. Its splendour declined over the centuries; by the twelfth, it was largely abandoned, feared and gloom-ridden, a refuge for thieves and ne’er-do-wells.

The film begins under that crumbling gateway, with rain that never lets up. A woodcutter, a monk and a beggar huddle there. Through flashbacks we hear what each claims to have seen. Tajōmaru, the bandit (a young Toshiro Mifune), tells his side. The samurai’s wife speaks out of pain and shame. Then, in a jolt, the samurai himself “speaks” through a medium. Each telling undoes the last. Gestures shift, motives change, and the truth thins out. What’s left is not certainty but a stark study of human weakness. Kurosawa gets there with techniques that, at the time, felt startling.

Thus, for instance, the camera slips into the forest’s thick undergrowth with tracking shots. Scenes alternate bright and dark cinematography, intercut with abrupt edits that feel like plunges over a cliff.

In moments like these, nature steps forward: sun through leaves, rain on the gate, a forest that works as a moral maze where nobody walks away clean.

What keeps Rashomon alive isn’t just style; it’s the problem it throws at us: how can we “know” the truth when each person bends it to get by? Kurosawa says it plainly: people aren’t fully honest with themselves; even with death close by, they hold to an illusion.

The film opened in Japan with modest hopes. The producers themselves weren’t sure about its broken structure. In 1951 it took the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival and, almost at once, Japanese cinema entered the Western conversation. Kurosawa was recognised around the world, and the stories of Ryūnosuke Akutagawa, the basis of the script, began to circulate outside Asia.

More than seventy years on, Rashomon is still alive. Not only as a classic of world cinema, but also as a mirror of what we are: people caught between memories, interests, and emotions that never quite fit together; pieces searching for one another in a jigsaw that always leaves a gap.

At heart, Kurosawa does not try to hand us a definitive truth. He reminds us how hard it is to reach. Truth does not assemble like a perfect mosaic; it appears in fragments, like looking into a cracked mirror: each shard reflects something different and never the whole.

21. Radio, Music and the Dawn of Television

Radio remained the main channel for sharing music, although in several countries more importance was given to local or international news, soap operas or sports information. Music programming varied greatly from country to country and, in many places, local stations broadcast only local or traditional music.

Television, on the other hand, was still a novelty. In the United States, only around 10% of households had a set in 1950, and in most of the world, TV broadcasting had yet to take root, or even begin.

Unlike in later decades, neither radio nor television had yet become a true launch pad for international hit singles. Programmes dedicated to new talent or recent musical releases were rare and often limited to local audiences. The idea of discovering music through televised performances still belonged to the future.

22. Music That Stayed Close to Home

In 1950, the music scene in the United States depended on where you were. In the big cities, for example, jazz was played late into the night. In other localities, blues was played at small gatherings, while country music was played in rural places through radios. And somewhere in between, a new name began to appear: rhythm and blues.

These sounds had been around for a while, each with its own crowd. But every now and then, in a bar, a dance hall, maybe even on someone’s back porch, they began to mingle. You could catch it in the way musicians borrowed riffs, or how certain beats crossed into unexpected songs. It didn’t have a name yet, but something new was taking shape.

People would later call it rock and roll. At that point, no one really knew where things were heading; they just felt the ground starting to shift. The borders between styles weren’t so fixed anymore, and little by little, the rules were being rewritten.

In Latin America, the music scene was full of emotion. Boleros were popular, and tango still held a strong presence. People danced to rancheras and tropical rhythms that would eventually evolve into genres like salsa and bossa nova, though no one was calling them that just yet.

Europe was moving to its own beat. In France, chanson was everywhere; often poetic, sometimes tinged with melancholy. In Portugal, people turned to fado, with its slow melodies and quiet intensity. Across much of the continent, folk traditions still held sway. Songs were passed down in families, sung in local languages, and closely woven into daily life.

There wasn’t much of a global music network. Songs rarely crossed borders, not because they lacked quality, but because there simply weren’t strong systems in place to carry them. Translation, licensing, and promotion tools did exist, but they didn’t reach very far.

23. Few Global Singers

Back in 1950, the idea of a global pop star just wasn’t part of the picture. Elvis hadn’t arrived yet, the Beatles were still in school, and Michael Jackson hadn’t even been born. Most artists who found success success at the time stuck to what people already liked. They weren’t trying to shake things up; they just knew how to make a tune that stayed with you, how to say something that felt real, and how to put on a show people wouldn’t forget.

Frank Sinatra, Édith Piaf, Nat King Cole… they were household names for good reason. Their songs travelled far, even if the world wasn’t quite ready yet for truly global fame.

But even artists of that calibre didn’t reach every corner of the world the way future stars would. The kind of success that crosses borders and languages was still something people hadn’t quite imagined.

The music industry had not yet turned its attention to young people. In 1950, there were simply children and adults; the word teenager was rarely used in everyday conversation. The concept of a youth market hadn’t yet emerged, although from the mid-1950s onwards, it would go on to transform the music business entirely.

24. Global Recording Industry: Uneven Paths

Some countries (such as Argentina, Mexico, Brazil and France) had relatively active recording industries, yet they remained isolated in terms of distribution.

Take Argentina. Even fifteen years after his death, Carlos Gardel’s voice was still everywhere. That’s how long a legend could linger at the heart of a nation’s culture.

Brazil had Carmen Miranda, a global star thanks to Hollywood. But back home, opinions were divided. Some celebrated her success; others felt that her sequinned version of Brazil didn’t quite match reality.

In much of Africa, music lived where it always had, in villages, at festivals, woven into daily life. Commercial recordings would come later, often shaped by foreign labels under colonial influence.

Behind the Iron Curtain, music faced tighter controls. If a song didn’t follow the party line, getting it pressed to vinyl was an uphill struggle. Under Stalin, creativity was kept on a short leash.

Meanwhile, over in Asia and the Pacific, music simply followed its own path. Japan’s film soundtracks pulsed with energy, India’s ragas spiralled into the heat of the afternoon, and islanders kept ancient rhythms alive, beautiful sounds that rarely travelled beyond their own shores. Not because they lacked brilliance, but because the world’s musical highways hadn’t reached them yet.

25. Notable Songs of 1950: Rare but Memorable

Although most songs recorded in 1950 stayed within their own borders, a few titles managed to travel further, sometimes right away, sometimes years later.

One example is “The Tennessee Waltz”, performed by Patti Page. It became one of the first popular songs in the U.S. to reach listeners from different social backgrounds.

Another is “Mona Lisa”, a soft ballad by Nat King Cole. Some songs just grew into classics without anyone noticing. That polished orchestra sound people loved back then? Plenty of tunes slipped right into that groove.

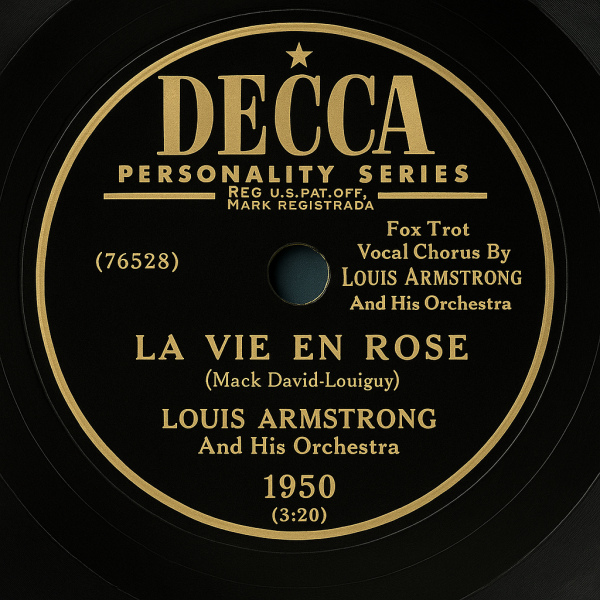

Take Édith Piaf's “La Vie en Rose”, recorded in the '40s, but really caught fire worldwide as the '50s rolled on. Same happened with “Bésame Mucho”. Mexican composer Consuelito Velázquez wrote it back in the 1930s, but the '50s turned it into a global favourite with cover after cover.

Then there's Brazil's “Tico-Tico”, that zesty little number written in 1917. Would’ve stayed local if not for Carmen Miranda’s fruit hats and Xavier Cugat’s orchestra giving it the full Hollywood treatment during the postwar years.

But these were, in truth, exceptions. Most of the music produced in 1950 remained local, fleeting, or modest in scope, shaped more by circumstance than by the search for global fame.

26. The Dawn of Change

The musical world of 1950 may have seemed modest on the surface, but change was already latent, constantly and irreversibly evolving.

In 1951, Gibson introduced the Les Paul, the first solid-body electric guitar. It didn't cause much of a stir at first, but it laid the foundation for the sound of modern music.

Just a year later, the LP (short for Long Play) started to catch on. It delivered better sound and longer playing time, letting listeners enjoy a full album without flipping the record. For many, it was the first time music became something to really sit with, not just sample.

In 1953, Ray Charles began experimenting with gospel and rhythm & blues. What emerged was raw, powerful and deeply moving; arguably the first manifestations of what we now call soul.

The very next year, everything changed when Bill Haley blasted “Rock Around the Clock” across radios nationwide. That wasn't just music. It was a thunderclap announcing a revolution was coming.

By 1955, two seismic shifts hit at once: Elvis Presley signed with RCA while Chuck Berry dropped “Maybellene”. They didn’t just perform songs: they rewrote the rules with every sneer and guitar lick. Almost overnight, popular music found itself heading somewhere entirely new.

Then 1956 happened, and rock and roll broke loose. Overnight, teenagers weren’t just killing time until adulthood, they were a movement with their own soundtrack. The music industry finally clocked it: this wasn’t just music to hear, it was music to live by. And just like that, the game changed.

27. Final Reflections

At its heart, 1950 was a year of slow gestation. The forces that would redefine the global music industry (technological, commercial, demographic, and stylistic) were still taking shape. The post-war world was rebuilding not just its cities and economies, but also its cultural landscape and everyday soundscape. In the absence of mass media saturation or globalised charts, music was still an intimate, regional affair, a fact that, in retrospect, adds a certain charm to the era. Though largely absent from today's algorithms, the songs of 1950 were the essential groundwork for everything that followed.

They are echoes from a time when music (with its sacred trinity of rhythm, melody, and harmony) did not need to go viral; it pulsed in unison with the very life of the city. It was enough to resonate in dance halls, cafés, cinemas before the curtain rose, or through valve radios that wove together sonic communities, long before the great digital homogenisation. In that state, now tinged with nostalgia, lies much of its charm. Many of that year’s songs may have slipped from popular catalogues, but their role in history remains decisive. Without them, nothing that followed would have been possible.

Essential Melodies, Curated by JGC

Musical Filter

Some of the criteria that helped decide which songs deserved a spotlight—and which were left behind:

Cultural Impact

How did it resonate in its time? Did it leave a mark on culture?

Sonic Innovation

Did it introduce new textures, rhythms, or techniques?

Lyrical Originality

Does it offer a unique poetic or narrative voice?

Recording Quality

Is the sound well-crafted, balanced, and professionally delivered?

Critical Reception

Was it praised by critics or fellow artists?

Artistic Risk

Does it avoid the easy route? Does it dare to offer something different?

Test of Time

Does it still sound fresh today?

Legacy

Did it influence other artists? Did it leave a trace?

Time Capsule

Does it capture something essential from its era?

Balance

Does it blend popularity with artistic depth?

Diversity

Does it bring linguistic, stylistic, or geographical variety?

The JGC Factor

A unique blend of intuition, experience and sensitivity. It cannot be measured, yet it is instantly recognisable.