1952

Silence, Structure, Experiment

A Time Capsule in Music Curated by JGC

Quick access to the music?

In a hurry or just keen to get straight to the music? You can go directly to the full selection of songs, with YouTube links and a Spotify player, using the buttons below:

Selection based on quality and relevance, not on algorithms or passing trends.

1. Introduction

In the sections that follow, the reader will encounter a curated selection of events, examined under a magnifying glass, that defined the year’s pulse.

We’ve chosen them with the precision, sensitivity and lucidity of a chess player methodically stepping through the possibilities one by one, as if visiting each branch of the tree of candidate moves.

Like brushing aside leaf litter from the board to reveal its strategic lines, this project presents a deliberate perspective: selective yet committed to a critical eye that distinguishes without reducing.

Just as in chess, that noble game where Capablanca and Kasparov achieved mastery through wholly different styles, we recognise that clarity wears many faces. Truth rarely follows a straight path, and the world around us invites multiple valid interpretations.

Readings with Substance and Style

Every section, every paragraph stems from deliberate choices shaped by a distinctive sensibility. We make no claim to universality; instead, we aim to sketch a freehand cultural portrait that weaves together eras, events, personalities and geographies. This is no neutral gaze, but a reading of the year shaped by both passion and precision.

Rather than striving for completeness, we’ve focused on meaningful brushstrokes: moments that resonate, historic turns that left a mark, discoveries that opened questions, losses that closed chapters, and births of those destined to play in the major leagues of their field. Films that distilled something essential of their time, and works (novels, manifestos, scores) that still speak with undiminished force. Our aim is not merely to recall what mattered then, but to highlight what, seen from today, continues to illuminate.

This same philosophy guided the shaping of our Top 50 and Top 100 rankings, even the flow from one melody to the next.

The thinking behind our choices? You'll find it all laid out near the bottom of the page, where we pull back the curtain on our selection process.

Let’s keep the conversation going

Music isn’t something to keep to ourselves. If a tune stayed with you, or if you noticed something missing, feel free to reach out. That small envelope icon at the corner? It's not merely decorative; it's there to carry insights across time and distance.

2. The Birth of the “Third World”

There was a time, not so far back, when the internet didn’t exist, Wikipedia wasn’t even a spark in anyone’s imagination, and getting answers wasn’t a matter of clicks. Finding out something we now treat as trivial could turn into a hit-or-miss endeavour, unless you had a solid library or happened to meet one of those rare souls, both a cultivated mind and a ‘living encyclopaedia’, generous enough to share what they knew.

Even in the 1970s, two decades after the early debates, it wasn’t uncommon to hear people assume that the terms First World and Third World had emerged together. Some, better informed, would date their supposed twin birth to 1952, as if they’d arrived at the same hour, destined to grow up as ideological rivals.

Although the Cold War was already unfolding by then, the language of these “three worlds” would take a few more years to take hold.

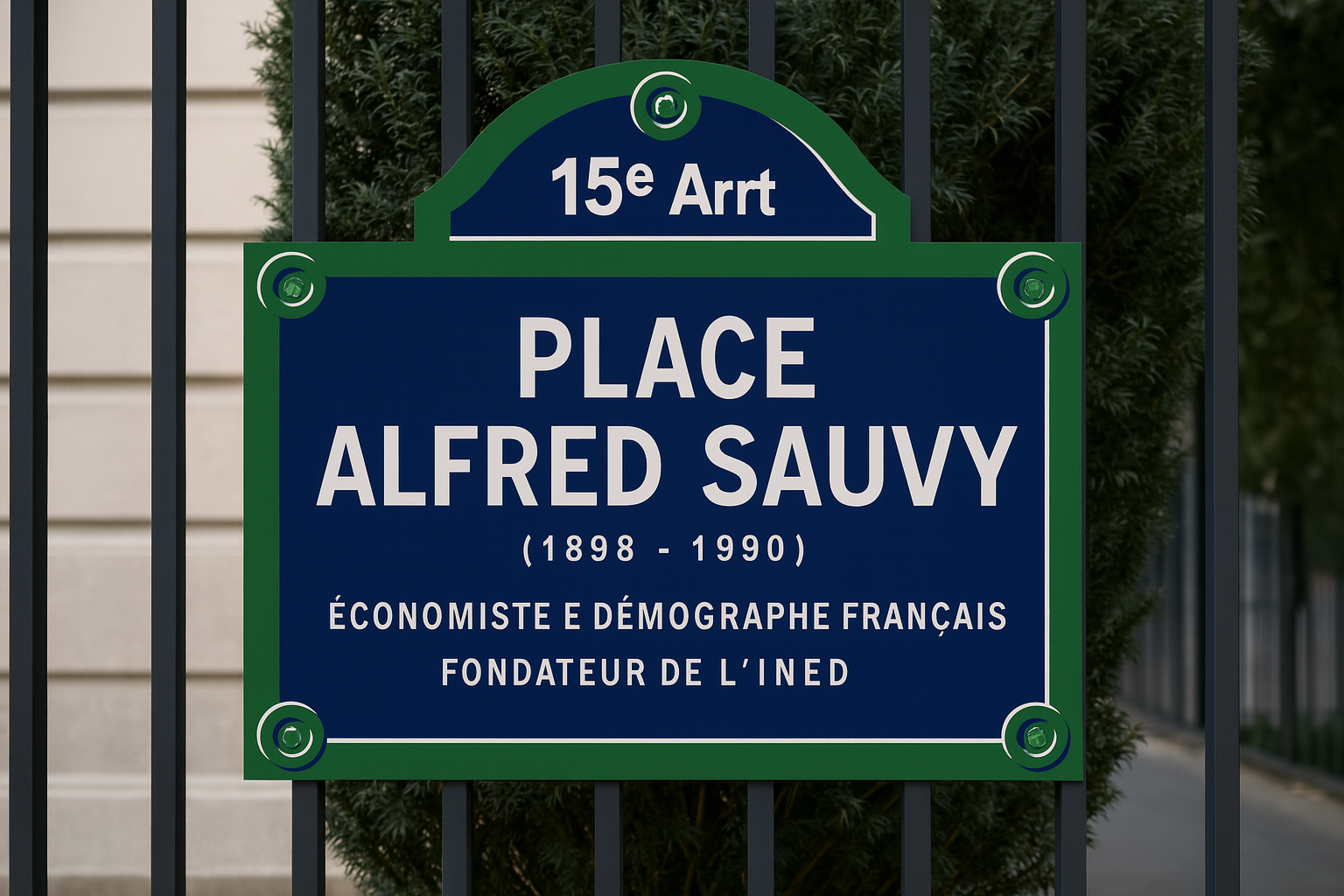

The expression Third World itself first appeared in 1952, when Alfred Sauvy, a French demographer with a keen political instinct, introduced it in a striking piece titled Trois mondes, une planète, published that August in L’Observateur.

“…ce Tiers Monde ignoré, exploité, méprisé comme le Tiers État…”

(“…this Third World, ignored, exploited, scorned like the Third Estate…”)

What Sauvy had in mind was the Third Estate of the French Revolution the ordinary people, the vast majority who didn’t belong to the clergy or the nobility. In his view, “Third World” wasn’t about GDP rankings. It was, above all, a political image: a way of pointing to those who had been pushed aside.

The term itself worked as a geopolitical alert. It drew attention to the countries that stood outside the Cold War’s two main orbits, neither part of the US-led capitalist bloc (which would later be labelled the First World), nor aligned with the socialist states under Soviet sway (the future Second World).

Ironically, those other labels came later. “Third World” was the first to appear, and only after its coinage did people begin to speak of a First and a Second, as if retrofitting the map to match the metaphor Sauvy had offered.

The world didn’t split randomly. It followed a clear geopolitical pattern.

First World: industrialised democracies, mostly capitalist, aligned with the US and NATO.

Second World: the group of socialist states orbiting around Moscow and tied to the Warsaw Pact.

These labels gained traction during the 1950s and 60s, a time shaken by two massive transformations: the collapse of colonial empires across Asia and Africa, and the rise of the Non-Aligned Movement a third path, proudly claimed by those who refused to be trapped between two superpowers.

3. Egypt: A New Path is Forged

It was the early hours of 23 July 1952 when tanks surrounded key points in Cairo. No announcements were made. A group of young officers had decided there was no more time to wait.

The monarchy of King Farouk I had long been faltering: serving British interests, complicit with the Ottoman Empire, but never truly loyal to the Egyptian people.

1948: The Blow That Opened Their Eyes

The humiliation of 1948 at the hands of Israel wasn’t just a military defeat. It was a moment of reckoning. Egypt saw its own decay: a weakened army, absent leadership, a nation betrayed by its own elite. For the young officers who lived through it, the loss was the final straw. In their eyes, the country could no longer continue down the same road.

In the early hours of 23 July, while the king slept in his palace, the military launched a swift operation that would change the course of Egypt’s history. The Free Officers Movement acted with precision. Within hours, Farouk was gone, forced to abdicate and leave the country. What fell with him wasn’t just a monarchy, but an old order that had clung to form over substance, to duration over true legitimacy.

Naguib Steps Forward

As dawn broke across Egypt, General Muhammad Naguib emerged as the public face of the revolution. His calm voice and serious demeanour gave the Revolutionary Command Council the credibility it needed, just enough to steady the country after a night of upheaval.

In that quiet space behind the scenes, a 34-year-old officer was already shaping what lay ahead. Nasser, a colonel from Egypt’s growing middle class, didn’t need speeches. His actions spoke for him. While the cameras lingered on Naguib, Nasser was quietly stitching together Egypt’s future; thread by thread, and tough as steel.

Long before anyone knew his name, Nasser had already begun to lead in his own way. At the Military Academy in Cairo, he stood out not for making noise, but for his quiet resolve. He didn’t push. He didn’t shout. And yet, people followed.

From Power to Vision

From then on, Nasser harboured no doubt. The country required nothing less than reinvention. This went beyond merely changing rulers. As we can imagine, this required forging a completely new concept of sovereignty. How do you restore dignity to a nation that has been treated as a mere pawn on the geopolitical chessboards of others? That question would define the rest of his public life.

A National Project with Regional Ambitions

Once in power, Nasser wasted no time. He came not with empty slogans, but with a clear vision. Egypt, he believed, had to stop playing the role of pawn. To do so, it would need three things: social justice, economic sovereignty, and a strong state that knew its own direction. The first battleground was the land.

Land First: Dignity from the Soil

For centuries, Egyptian land had remained out of reach for those who tilled it, locked away in the hands of a privileged few. Nasser broke that pattern. His land reform was not just a policy. It was an act of justice. He dismantled the great estates, redistributed the fields, and for the first time, gave peasants something sacred: a patch of earth they could truly call their own. It was more than land. It was dignity.

Next came the economic reckoning. Nasser pressed on, pulling banks, insurance companies, and major firms out of foreign hands and placing them under Egyptian control, one by one. It wasn’t greed. It was a cry for sovereignty. At last, the economy would breathe through its own lungs, no longer subject to decisions made in distant boardrooms. Factories roared to life, schools opened their doors to thousands, and the state reached further than ever before. As a towering symbol of that whirlwind of transformation, the Aswan Dam rose, a colossal “We are here!” carved in concrete across the Nile.

Built with Soviet backing after a Western snub, it became far more than a feat of engineering. It meant control over water, over electricity, over the Nile’s pulse. In other words, over Egypt’s destiny.

Suez Shock: Egypt Defies the World

But the move that really made him a global heavyweight came in 1956, when he dropped the bombshell: the Suez Canal was now Egypt's, no take backs. Until then, the important waterway, which was very important for international trade, had been controlled by Britain and France. In the capital cities of the West, his move was seen as a deliberate insult. Within days, the United Kingdom, France and Israel launched a joint military response.

Egypt fought back as hard as it could. But the real game changer came out of left field, in the frosty world of backroom diplomacy. Incredibly, both the US and Soviet Union, bitter Cold War enemies at the time, suddenly found common ground and demanded the invaders back off immediately. Against all odds, the canal returned to Egyptian hands. Nasser, the man who had dared to defy the powers of the world, emerged as the great symbol of twentieth century anti-imperialism. It was more than a refusal. It was a roar that echoed across the Arab world.

Bandung and the Non-Aligned Dream

But Nasser had bigger ambitions than just Egypt. By 1955, with Bandung’s revolutionary energy buzzing across Asia and Africa, he was already playing the long game. He teamed up with Nehru in India, a man with ideas decades ahead of his time, Tito in Yugoslavia, a streetwise hardnut who wouldn’t bow to anyone, and Sukarno in Indonesia, all fiery speeches and magnetic charm. This wasn’t just diplomatic small talk. These blokes actually thought, mad as it sounded, that the world could dodge the whole East–West carve up.

Wikimedia Commons – public domain.

This was no mere strategy. It was conviction. Together, they believed, dared to believe, that the world need not be pulled forever between Washington and Moscow. That fragile dream of Bandung would take root in time, and grow into the Non-Aligned Movement.

The Arab World Awakens

At the same time, a different vision was quietly taking root across the Arab world — one anchored in memory, yet reaching for something new. People began to wonder: if we share a language, a past, and a long history of struggle… why not imagine a future together as well? It was a daring thought, maybe even improbable. But it caught fire. From the quiet bays of the Gulf to the restless shores of the Atlantic, something began to stir. Across deserts and cities, more and more people found themselves wondering: could unity be more than a dream?

What if they were no longer scattered pieces on a board drawn by colonial hands? In 1958, Egypt and Syria dared to answer. Together, they founded the United Arab Republic. It was bold. It lasted only three years. Yet its failure did not extinguish the spark. In countless streets and hearts, there lingered the sense that something precious had almost come to life.

The Light and Shadow of Charismatic Leadership

Nasser's leadership brought great promises, but also a firm grip on the reins. Social justice remained a key theme in his discourse, even as control tightened and authority became increasingly centralised.

The dream of unity soon took a darker shape. Political parties disappeared, replaced by a single body: the Arab Socialist Union. This was no mere rebranding. Bit by bit, Egypt turned inward. Dissent found itself with less and less room to breathe. The press was restricted, constrained by layers of censorship. The Mukhabarat began to infiltrate homes, streets and whispered conversations, quietly at first, but relentlessly. Its chilling presence spread everywhere. No one was truly secure: neither the communists, nor the Islamists, nor even ordinary citizens who dared to voice their thoughts. Many were thrown into prison. Others were sent into exile. Some simply vanished. The early hope, once bright and full of promise, slowly began to sour, as fear and repression seeped into daily life.

Nasser never saw himself as a dictator. In his eyes, only a strong state could prevent the old elite from reclaiming their privileges and protect the hard-won gains of the people. But this obsession with keeping the ship steady came at a price. For many Egyptians, basic freedoms were gradually frozen — suspended in the name of stability. And over time, even his supporters had to face the truth: what began as a temporary measure had quietly become the very basis of his rule.

1967: The Shattering Defeat

The most crushing setback struck in June 1967. In a matter of just six days, the Israeli forces effectively defeated the combined armies of Egypt, Syria, Jordan, and Iraq — a significant blow to the region. Egypt lost the Sinai Peninsula. Its air force was left in ruins, most jets destroyed before they could even take off. The sense of military pride — painfully built over years — lay shattered.

Nasser, clearly shaken, appeared on television and said he was stepping down. But the response caught everyone off guard. People filled the streets — no slogans, no party banners — just raw emotion. They called for him to stay. And he did. He returned to power. But something in the air had shifted.

Fading Aura, Fractured Unity

From that day, the aura around him began to fade. The dream of pan-Arab unity no longer burned as bright. Frictions between neighbouring countries deepened. And quietly, almost imperceptibly at first, new currents began to move.

The Final Chapter: Legacy and Ghosts

Nasser held power right up until his September 1970 death, though by then his influence was clearly waning.

Amazingly, even some of his former critics had to admit that he had led with courage and shouldered the weight of his country with great dignity.

He got many things right — and quite a few wrong. Still, no one can deny the depth of his impact.

Looking back, one thing becomes clear:

Nasser was nothing if not the boldest leader to have ever tried to reshape the Arab world in the 20th century.

A Legacy of Contrasts

His legacy, though, defies simple labels. To many, Nasser was the last great leader of the Global South — a statesman with the guts to say no, who stood up to colonialism with dignity and carved out Egypt's own place in the world. To others, he built an authoritarian system that crushed freedoms and left state structures too rigid to adapt.

Both versions contain truth. Because Nasser left behind a country that was more literate, more industrialised, and more self-aware. But he also bequeathed a state-controlled economy, an omnipresent security apparatus, and no real political alternatives. His dream of Arab unity fizzled out.

Nasser dreamed big. For a time, it actually worked. But like most grand designs, his vision couldn’t last forever.

The Ghost in the Nation

Funny thing is, over seventy years since that fateful dawn in '52, you still can't shake his ghost in Egypt. Not because he was flawless — far from it — but because he had the bottle to aim higher than anyone expected. He didn’t parrot other people’s lines; he wrote his own script. And just for a moment, he made a broken nation believe it could stare down the world with its head held high.

Let’s be clear: he was no saint, but neither was he an empty myth. At his core, he was that rare leader who turned a nagging question into something real:

What does being truly sovereign actually mean?

4. Bolivia: A Revolution Mirrored in Other Nations

As we saw in the previous section on the Egyptian process, 1952 was much more than just a year of political change. It was a breaking point. A moment when very different peoples, in distant corners of the world, said: enough.

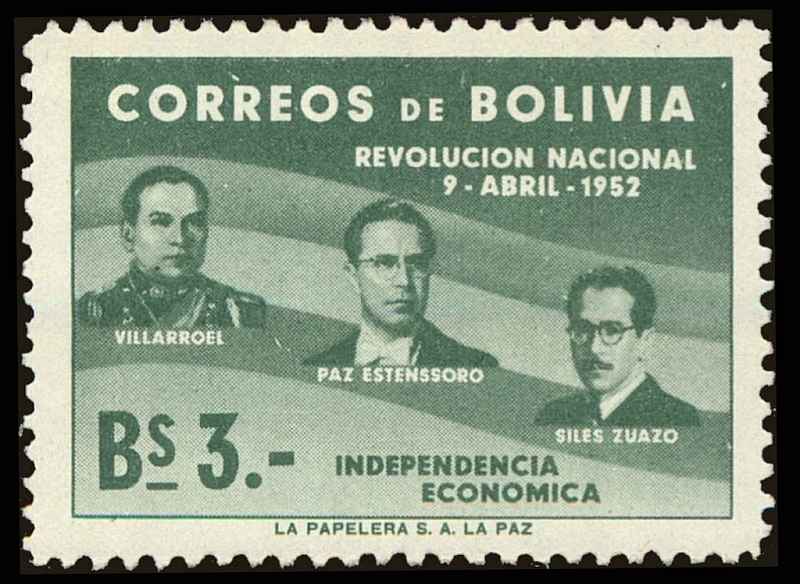

In Bolivia, that break took shape in April. With the backing of miners, farmers, and working-class Bolivians, the MNR managed to topple the country’s entrenched oligarchy—marking a turning point in Bolivia’s modern history. The mining oligarchy collapsed. The traditional army was dismantled. Universal suffrage was introduced. What was buried wasn’t just a censitary system—it was an entire social hierarchy that had remained intact since colonial times.

Something similar, as we saw, happened in Egypt. The fall of King Farouk I, led by the Free Officers, was not merely a military manoeuvre. It was a direct rejection of decades of British dominance, feudal privilege, and inherited humiliation. What links both processes is not the method, nor the context. It’s the nature of the rupture: a bottom-up revolt. A cycle that had reached its end.

Structural Reforms in the Name of Sovereignty

As often happens after a true rupture, the changes did not stop at symbols. In neither Bolivia nor Egypt was it simply about replacing names or flags. What followed was deep. Structural. Almost foundational.

In Bolivia, the new government seized control of the tin mines — previously the private fiefdom of a handful of powerful families. Overnight, the political game changed. Indigenous communities finally got their say, miners brought the realities of pit life straight into parliamentary debates, and women took their rightful place at tables where decisions were made.

Egypt’s shift came more gradually, but no less deeply. Once Nasser was firmly in power, the government seized control of the Suez Canal from foreign powers — a masterstroke against colonialism that reverberated throughout the Arab world. At the same time, a redistribution of land was set in motion with the aim of dismantling the old system: reducing the dominance of the powerful dynasties that had monopolised rural property for generations.

In both cases, the State positioned itself as the guarantor of reclaimed sovereignty. Not only in the face of foreign interests, but also against its own entrenched elites. What was at stake wasn’t just the economy—it was the very question of who held power, and on whose behalf.

What was at stake wasn’t just the economy—it was the very question of who held power, and on whose behalf.

A Nationalist Epic with a Modernising Spirit

When they took office, Nasser and Paz Estenssoro represented something new — leaders who hadn’t been born into privilege but who spoke as if the whole nation stood behind them.

Nasser’s father had been a post office worker in Alexandria. Paz Estenssoro, an academic turned politician, gave voice to popular anger without needing army support.

Their speeches weren’t just about promises. They carried an epic tone, almost foundational in style. They spoke of industrialisation, of equality, of nations that would no longer see themselves as satellites of others.

Each in their own way promoted a modernity that wasn’t imported or imitated. It was a modernity that sought to be native — built on social justice, state planning, and national pride. Neither liberal nor communist: something in between, born from the soil they stood on.

Though their approaches contrasted sharply — the fiery military man versus the measured civilian reformer — both men wove the same powerful story: that government should finally answer to ordinary people rather than the privileged elite.

Inspiration from the Global South

Bolivia and Egypt's revolutions didn't happen in a vacuum. What happened in La Paz and Cairo — and in neighbouring countries — showed how both nations were part of something bigger. While their revolutions ultimately took different paths, they were united by something powerful — that surging sense of throwing off colonial rule that was electrifying what we'd now term the Global South.

Egypt's story stands out. Nasser didn't just lead a coup — he became one of the most important voices in the Non-Aligned Movement. Before long, his influence stretched far beyond the Middle East. The way he stood up to empires, refused to pick sides in the Cold War, and called for Arab unity gave Egypt a kind of global megaphone. For many countries just shaking off colonial rule, Nasser's Egypt showed what might be possible.

Bolivia did not formally join that global movement, yet it shared many of its instincts. A rejection of foreign interference. An attempt to design its own model of development. It is clear that there is a determination to break free from the peripheral role that history has long assigned to it. As one would expect, its revolution – with all its contradictions – would go on to inspire several Latin American movements in the decades that followed.

At heart, it was the same question. It was echoing in different languages:

Can a people build its own future without borrowing someone else's formula?

Can there be sovereignty without justice?

And justice, without memory?

5. Cuba: The Quiet Coup

So much has been written on the subject that we'll mention it tangentially. Not because it isn't important, but because we suspect the reader already has a good deal of information. In any case, the tremors kept coming.

In Cuba, Fulgencio Batista decided he’d had enough of waiting. It was March. One night, without a fight or fanfare, he just... took over. No tanks in the streets. No speeches from balconies. Just quiet meetings behind closed doors, and suddenly—he was back in charge.

The elections? Gone. The constitution? Ignored. He made it look easy. Too easy.

Batista understood the art of power. He kept Havana's casinos glittering, let American tourists sip their rum cocktails undisturbed, while his men in dark suits made troublesome voices disappear. The bitter twist? His corruption would become the perfect fertiliser for the revolution that would bury him.

We shall deliberately leave this brief yet telling section devoid of imagery. Often, absence itself transforms into the most eloquent visual statement.

It brings to mind how I taught combinatorics to my students: when hosting a party, one does not merely send invitations to attendees—one simultaneously, if subtly, extends an invitation for all others to stay away.

Such is the language of symbols: a paradoxical inclusion where, in the final reckoning, all are invited... if only by omission.

6. Korea: Frozen Frontlines

Meanwhile, in Korea...

Picture this: endless winter in a land where war had forgotten how to end. By 1952, young men from American farm towns and Korean villages found themselves bound by the same cruel rhythm—advance, retreat, repeat. They fought not for victory, but for another sunrise. Although generals continued to use flags on maps, soldiers were acutely aware that this was now a war of endurance, measured in frozen breaths and inches of mud.

From Havana to Korea: Shifting Ground

Two distant fronts, one unmistakable feeling. From the sun-drenched yet oppressive plazas of Havana to the frozen trenches of Korea, established certainties were beginning to unravel.

Most people couldn’t quite put it into words. But something was changing. You could feel it, in headlines, in silences, in the way nations looked at one another.

And if you’d been really listening in 1952, you might have caught it too: a low, persistent murmur—countries beginning to move differently, to rethink the rules of the game.

7. New Frontiers: From Hydrogen Bombs to Double Helices

The Cloud Over the Pacific

On 1 November, the Americans detonated the bomb. A mushroom cloud rose above the Pacific and a small atoll vanished. The test was called Ivy Mike, but its true meaning defied language.

They had tested bombs before — but this one was different. On that day in 1952, the United States detonated a hydrogen bomb for the first time. A flash, a roar, and an entire atoll gone. After that, people stopped assuming the future would hold steady. Things felt… less certain.

There was no turning back. The idea of a safe world didn’t disappear, but it started drifting, like something unmoored, too light to hold its place.

A Spiral, Quietly Unfolding

Not far from the headlines and mushroom clouds, a quieter moment was unfolding — one with no noise at all. In a London lab, Rosalind Franklin adjusted her equipment, steady as ever, and exposed a bit of film to an X-ray beam. That photo, still nameless then, would one day be known as Photo 51.

At the time, it was just a piece of film — silent, delicate, and filled with meaning no one had fully seen yet.

There were no journalists, no headlines. Just a luminous image tucked away in a drawer, holding a secret that would change everything.

No explosions, no uproar. Just a strip of film revealing something hidden: the shape of DNA. A spiral, fragile and precise, emerging under the glow of X-rays — life caught mid-turn.

One Date, Two Thresholds

Two breakthroughs. Two directions. On that same day, the world learned how to destroy itself — and how to understand itself.

8. Argentina: Evita's Farewell

Public domain in both Argentina and the United States. Details available in the original Wikimedia Commons record.

In Buenos Aires, the streets were heavy with roses. Quiet. Slow. People stood shoulder to shoulder, not saying much, just… being there.

Eva Perón was only 33 years old, yet already a legend, when she passed away on that chilly evening of 26 July 1952. A few months earlier, the National Congress, for the first and only time in history, had bestowed upon her the title of Spiritual Leader of the Nation.

Some saw her as a kind of saint in a retablo. Others… something else entirely. She polarised, fascinated, burned with that rare intensity only living myths seem to possess.

What followed wasn’t just a funeral. It was as if the whole country had stopped breathing, trying to grasp something deeper. People weren’t just weeping — they were looking into a mirror of death, asking what she had meant. And what they meant, too.

Just months earlier, she had done the unthinkable: Argentine women voted in a national election for the first time. That right didn’t arrive in pastel envelopes tied with bows. She tore it from history with speeches and with that fierce resolve of hers that didn’t recognise “no” as an answer.

9. A Year of Quiet Legitimations

In Chile, women voted for the first time in a presidential election. The country had taken its time. But on 4 September 1952, at last, they stepped into history, with ballot in hand. With no restrictions. No literacy requirements. No obligation to be married. No property qualifications. It was made possible by Law No. 9,292, enacted in January 1949, which finally granted women the right to vote in national elections (source).

Across the Atlantic, Spain found a narrow opening. It was not yet admitted to the United Nations, but it was allowed to join UNESCO. A modest step, yes. But a first one. The Franco regime was beginning to emerge from isolation.

Two unrelated events. Two contexts with no bridge. And yet, a shared thread: both sought something similar — legitimacy.

A right won by the long-neglected half of the citizenry. A return, if only partial, to the international stage. Ballot boxes and diplomatic halls don't usually have much to say to each other. But in 1952, they actually did.

10. England: A Young Queen and a Silent Dawn

The morning mist of 6 February 1952 still covered the gardens of Sandringham House when King George VI had stopped breathing a few hours earlier. His daughter, Princess Elizabeth, just twenty-five, became queen without fanfare. No bells rang out. No grand procession filled the streets.

The coronation would come later – not for sixteen months yet – but that winter morning needed no ceremony. In the predawn quiet, three realities took shape: a Britain still rationing butter seven years after VE Day; an Empire where the sun was setting rather than rising; and a princess still in the spring of her life, for whom the crown had come too soon.

No one yet grasped how she would steady the ship through the storms ahead. The cracks in imperial glory were already visible, but she would learn to hold together what was already slipping beyond saving.

But this new sovereign, against all odds, would guide its metamorphosis into something new: not with grand decrees, but with quiet resolve.

That same year, the European Coal and Steel Community came into force – founded by six nations, not in marble halls but in a modest meeting room far from palaces. On paper, it appeared to be little more than economic co-operation between neighbouring states. Yet, like the Queen’s accession, it quietly planted seeds of revolution. Unwittingly, those bureaucrats were placing the first stones of what would become the European Union.

Two subtle beginnings in one remarkable year:

- A monarch inheriting an empire in twilight

- Technocrats building peace through coal quotas

History doesn't usually make a big fuss about its big moments. Sometimes, the most profound changes arrive softly – in the rustle of parchment, in a young woman's breath before taking the oath, or in the dry language of trade agreements that would one day link entire continents together.

11. Jonas Salk: when science tuned the silence

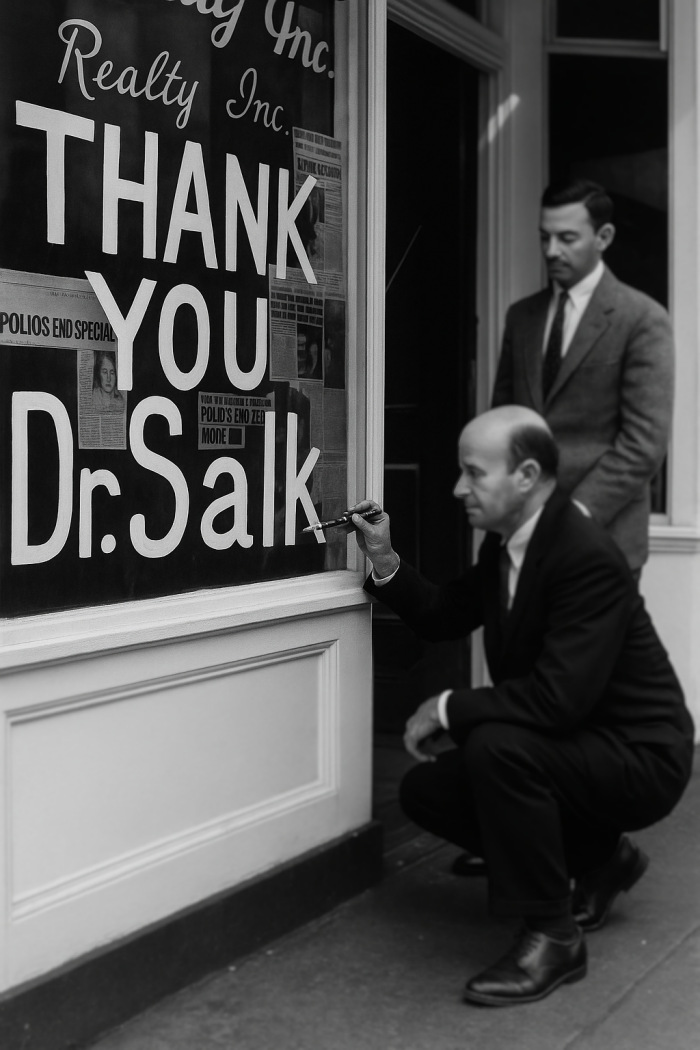

While some were slow-dancing to Cry, that trembling lament Johnny Ray took to number one in March 1952, America’s hospitals were overflowing. The polio epidemic had reached its peak.

Parents lived in quiet dread. Hospital wards overflowed — rows of cots, the hum of machines, and too many whispered prayers. Callipers and leg braces stood in line, like small, unwanted omens.

In a Pittsburgh lab, far from media attention, Jonas Salk worked methodically. By mid-1952, he was testing his inactivated polio vaccine on an unexpected group: children recovering from polio who remained institutionalised at the D.T. Watson Home.

This was no improvised trial. It followed strict procedures, relied on independent oversight, and by the following year, the results would be published in JAMA, for all to see.

For the first time, there was a scientifically grounded promise.

Salk’s approach stood in contrast to Hilary Koprowski’s earlier efforts — an oral vaccine with live virus, tested years before, but without full disclosure of methods or results.

While Johnny Ray’s broken voice told listeners that tears might bring relief, medicine — between weeping and statistics — was starting to carve a way out.

12. Hemingway: ‘The Old Man and the Sea’

In 1952, while Batista was busy strengthening his control over Cuba's political future, as we mentioned in a previous section, something quieter and more noble was happening on those same shores: all you could hear was the splashing of oars, the murmur of the waves, and an old fisherman going out alone to fish. That was the year Hemingway gave us The Old Man and the Sea and, with it, a question that still lingers: what does it mean to persevere when the world has stopped watching?

By then, Hemingway wasn’t just a writer — he was a force. The Sun Also Rises had already pinned down the restless heart of a generation. A Farewell to Arms showed us war’s cruel romance, all field hospitals and stolen moments. Then came To Have and Have Not, where survival wasn’t heroic, just desperate. And For Whom the Bell Tolls? That one didn’t just talk about war — it made you feel the weight of a bridge, and what it means to choose.

When it comes to Across the River and Into the Trees, it’s not his best — and Hemingway knew that. Some parts feel flat. But even there, he kept circling around what mattered to him: the way love fades, the way people leave, the quiet dread of knowing the end is near.

As the years went on, his sentences got leaner. Not cold — just honest. He stripped away everything he didn’t need. And somehow, in that bare-bones rhythm, he managed to hold entire oceans of feeling without ever saying too much.

What the Old Man Teaches

Santiago is an old fisherman living in a small Cuban village. He hasn’t caught a fish in eighty-four days. People start to say he’s cursed — salao. Even the boy who used to fish with him — his only real companion — is moved to another boat by his family.

Still, every morning, Santiago rows out alone into the open sea. Not because he expects to succeed. Not because he wants to prove anything. He goes because it’s what he knows how to do. It’s his way of being in the world.

There’s something deeply human in that. The idea that you keep going, not for reward, but because stopping would mean giving up a part of yourself.

Grace in the Struggle

It’s not dramatic. It’s quiet. But that kind of persistence — of showing up when no one’s watching — is the kind of courage we often forget to admire.

The marlin comes. The sharks follow. The ending? Well, you know it. But here’s the thing: the power of this story isn’t in the plot. It’s in the way Santiago loses. Gracefully. Without surrender. As if to say: you can take the fish, but you can’t take the fight.

Seventy years later, that still stings, doesn’t it? In a world obsessed with metrics — likes, wins, visible success — Santiago’s stubborn dignity feels almost radical. What’s your marlin? The thing you’d chase, even if no one ever saw you do it?

Hemingway didn’t write a fishing manual. He wrote a mirror. And somehow, after all this time, it still reflects us back — raw, relentless, beautifully human.

When he finally hooks the marlin, the tale doesn't become a battle of good versus evil. There’s no villain here. Santiago calls the fish “brother”. He admires its beauty, its power, its resolve. And in that long, drawn-out struggle — man against creature, will against nature — there’s a strange sort of grace. The fish is not the enemy. At the end of the fight, what remains isn't the trophy but the proof of who you were when everything was against you.

Of course, the sharks come. They always do. They strip the marlin to the bone. Santiago returns with little more than a skeleton lashed to the side of his skiff. But here’s the question Hemingway slips in beneath the salt and the silence: was it failure?

Most people would call it failure. No prize, no fish, nothing to show for all that effort. But Hemingway doesn’t agree — at least, not out loud. He lets the story do the talking. And what it suggests is simple: the real worth is in showing up, especially when you know how it might end.

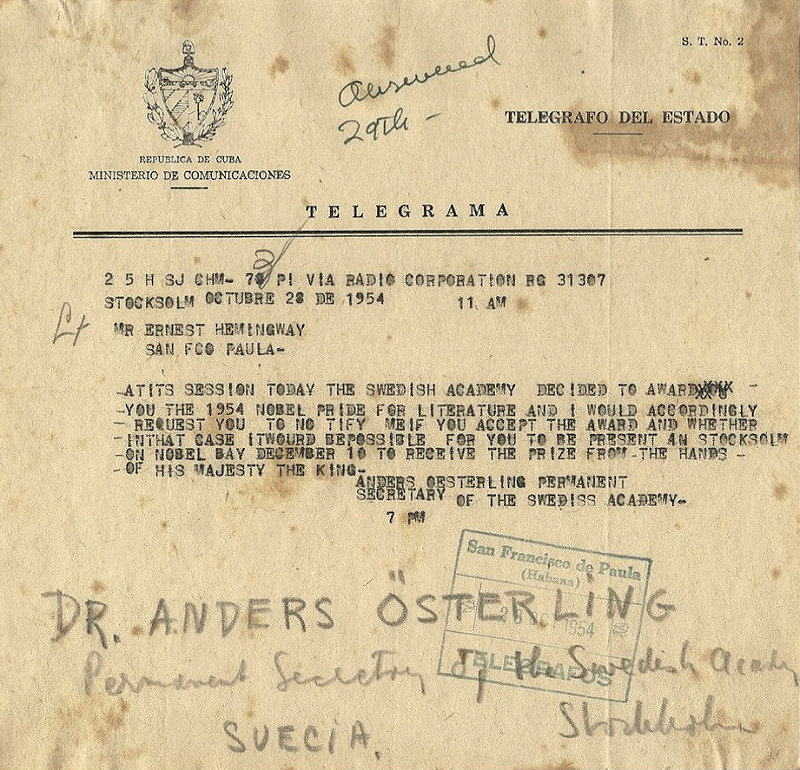

It was that quiet strength that helped make the book a success — and earned Hemingway the Pulitzer Prize in 1953. Then, just a year later, when he got the Nobel Prize in Literature, this was the work that did the trick.

What gives The Old Man and the Sea its weight isn’t what it explains, but what it leaves unsaid. There are no big speeches. No symbols jumping off the page. Just clean, careful writing — like fishing line slipping through salt water. Hemingway lets the silence do the work.

And if the story had a soundtrack, it wouldn’t be a grand orchestra. It’d sound more like Chuck Mangione’s Feels So Good — soft brass, something gentle but full of feeling. That same mix of warmth and sadness runs through the pages.

You think about this story at strange hours. At three in the morning. Or while watching someone quietly do something difficult for no applause. Because we all face our marlins — the dream that keeps slipping away, the thing we care about more than is reasonable, the fight no one else sees.

And Hemingway doesn’t promise victory. He promises clarity. He reminds us, in the most Cuban of settings, that there is honour in persistence, even when the world takes what little you bring back. That you can be destroyed, yes — but not defeated.

That, seventy years on, is why we still row out with the old man.

13. The Class of ’52: The Art of Stylish Rebellion

In 1952, the world welcomed a generation of babies who would grow into revolutionary musicians, composers and performers. They didn’t just sing: they invented new ways to give sound to their view of the world. They all wrote. They all sang. Each, in their own way, disobeyed. Because rebellion wears many faces.

From the South came Nito Mestre (1952), one of the most precocious of that generation, already revealing his voice with folk guitars and tender lyrics in Sui Generis. The world was hostile, but his voice was a refuge. Like other musicians of his time, he performed songs that opened windows. And together with the brilliant Charly García (1951), they burst onto the music scene as teenagers, changing Spanish-language rock forever.

In a similar way, Dewey Bunnell (1952) wrote “A Horse with No Name”. With Gerry Beckley (1952) on twelve-string guitar and Dan Peek (1950) on bass, they released this iconic song in 1971—the first two before turning twenty. It wasn’t just a desert journey: it was a metaphor. The song blends escape, introspection and environmental critique, wrapped in an aura of mystery that invites multiple readings. What makes it beautiful is precisely its ambiguity.

Original image published by AVRO and now available under the Creative Commons BY-SA 3.0 NL licence, via Wikimedia Commons.

This restored version aims to preserve the intimate atmosphere of one of the musician’s most iconic television appearances.

From the damp streets of Britain to the fog-bound coasts of Ireland, Joe Strummer (1952) lit a fuse with Combat Rock (1982). It wasn’t just another album with The Clash—it was a flare in the city night. Rock the Casbah didn’t preach. It jabbed, danced, and mocked. Fanaticism took the hit, and resistance got a beat. Even now, that song still slips past censors. Still says what others won’t.

Original photo by Megalit, shared under the Creative Commons BY-SA 4.0 licence, via Wikimedia Commons.

Gary Moore (1952) took blues to its emotional limit with “Still Got the Blues”—each note a truth he couldn’t quite say. This elegy for lost love shows how music and poetry say what time refuses to erase. Its greatness lies in its universality: anyone who’s loved and lost can see themselves here.

Original image by LivePict.com, available under the Creative Commons BY-SA 3.0 licence via Wikimedia Commons.

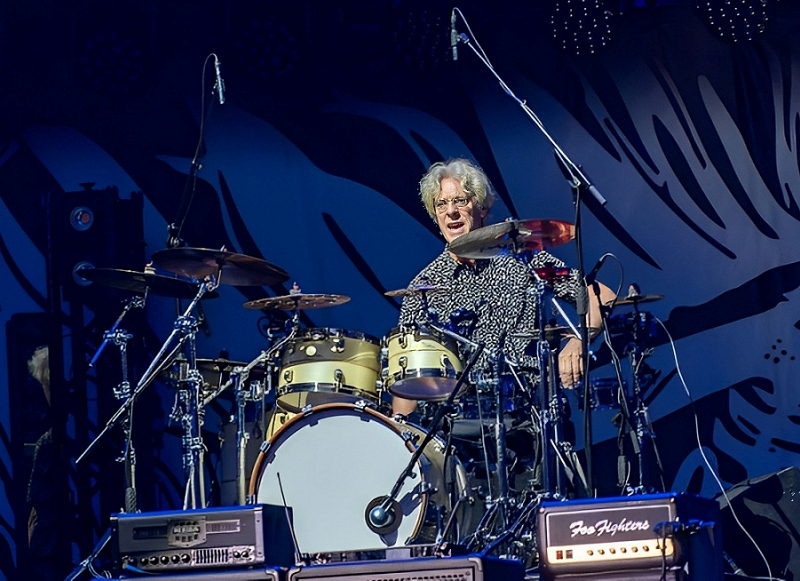

Stewart Copeland (1952) didn’t play the drums—he carved through them. Snapping backbeats, reggae grooves, sudden stabs of syncopation—his kit spoke in riddles. With The Police, he built something strange and wild: punk with a nervous pulse. He rarely wrote lyrics, and when he did, they veered into odd places—part theatre, part inner monologue. But it was the rhythm that stuck. He made rebellion sound precise.

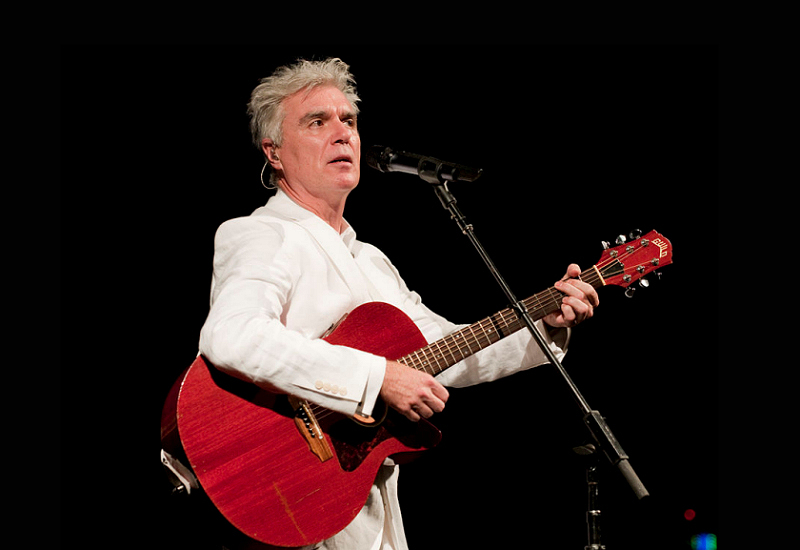

In 1977, David Byrne (1952) gave us “Psycho Killer”: danceable anguish, irony worthy of a museum. Together with his band Talking Heads, he exposed urban alienation through a killer who, far from being a monster, reflects the breakdown of a sick society. The line “I hate people when they’re not polite” reflects his twisted logic. And the contrast between the catchy rhythm and the violent lyrics calls out our indifference to modern madness. It turns existential unrest into paranoid funk.

By 1979, Paul Stanley (1952) stunned audiences with “I Was Made for Lovin’ You”, fusing KISS’s stadium-sized hedonism with disco glamour – a bold gesture of reinvention.

They were all born in 1952. Not one of them copied anyone. That’s why they still matter. Even when the world falls silent.

14. Education, Mathematics, and Legacies That Endure

We could go on — there’s so much still to explore — but at some point, a pause is needed. A stop in the pit lane, so to speak. And so, as we approach the close of this cultural kaleidoscope that was 1952, it feels right to pause and remember three figures whose lives, though different in form, share a deeper thread — and resonate closely with our daily work.

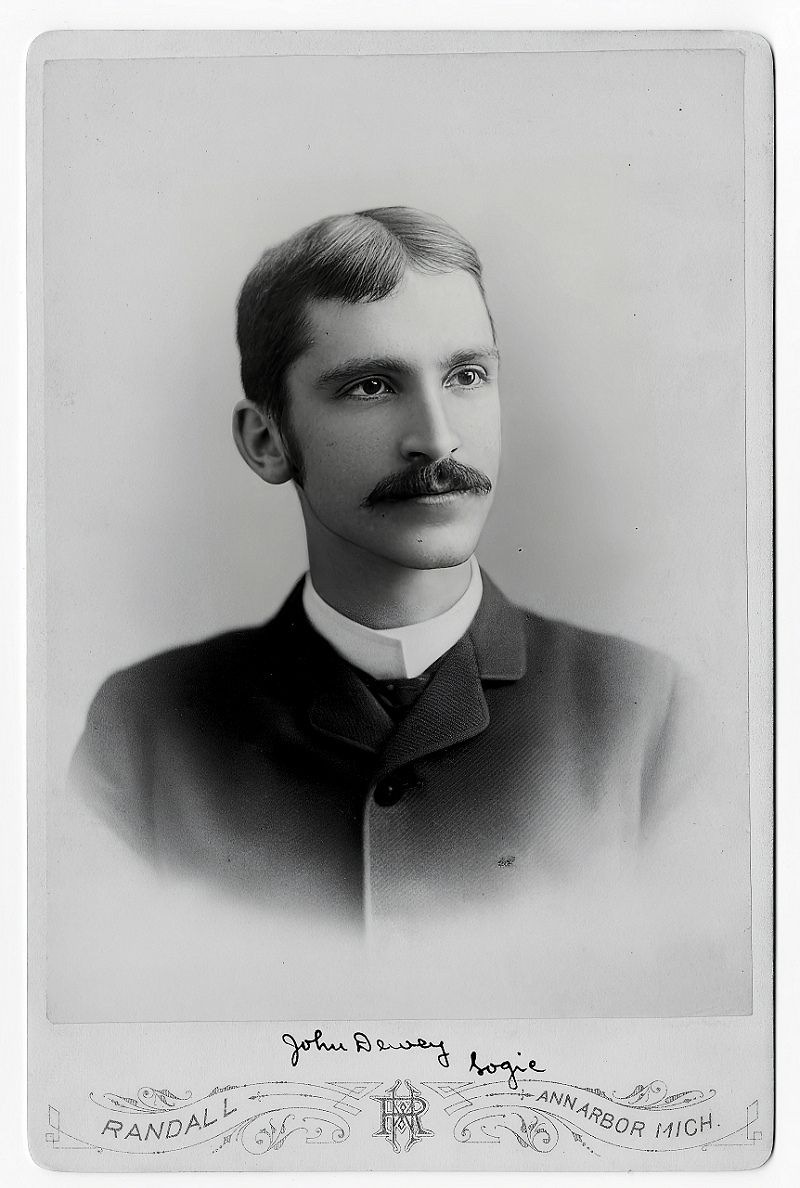

Two of them were giants in the field of education. Their ideas changed, irreversibly, the way we understand learning and human development. John Dewey and Maria Montessori.

John Dewey and Maria Montessori both died in 1952 — a year with more than its fair share of upheaval and change. Their absence was real, but their presence didn’t fade. Even now, their ideas live on — in classrooms, in teaching methods, in the way we talk about learning itself.

That very same year, Vaughan Jones entered the world. He wouldn’t shape education, but decades later he’d transform mathematics. Years later, he received the Fields Medal — a rare honour in mathematics. Some even see it as the Nobel’s counterpart. What earned him that prize was a set of discoveries that linked knot theory with ideas from quantum physics in ways no one had expected.

What links these three names? More than mere chronology, it’s a shared pursuit — the search for hidden structures that shape how we think and how the universe unfolds.

Dewey and Montessori both championed an active model of education: rooted in experience, open to play, and led by exploration. Dewey believed in learning by doing; Montessori spoke of a space where natural curiosity lights the way.

Jones, for his part, uncovered unseen patterns — including the now-famous Jones polynomial — that revealed an unexpected order within topological knots and deep regions of quantum physics.

Each, in their own way, explored how underlying structures — pedagogical or algebraic — might unlock human potential. Dewey and Montessori sparked revolutions in the classroom; Jones did so with chalk and board.

Their legacy speaks to us still. It shows that whether we’re looking into the mind of a child or the folds of space-time, curiosity, precision and a sense of wonder can open the way to understanding.

With that thought, we’ll wrap up our journey through the cultural landmarks of 1952 — a year that, as you’ll soon discover, also made a lasting mark on the world of music.

A quick note: Every track title links to YouTube – a platform we’re rather fond of, truth be told. Why? Because it lets you explore each song at your leisure, like carefully lowering the stylus onto a well-worn vinyl record. Admittedly, it’s not the quickest way to listen – but then, where’s the joy in rushing? Some of the best discoveries hide in the cracks between tracks.

Nearly every artist name links to their Wikipedia page as well (we’ve done our homework, mostly). We rather like the idea that after hearing a song, you might fancy digging deeper – perhaps learning who wrote it, or which dimly-lit garage it was recorded in. Curiosity costs nothing, after all.

And if you’d rather cut straight to the chase (as we mentioned earlier), you’ll find the playlist waiting below on Spotify. No fuss. No formalities.

Essential Melodies, Curated by JGC

Georges Guetary & Bourvil

Musical Filter

What helped certain songs shine while others faded into the background.

Cultural Impact

How did it resonate in its time? Did it leave a mark on culture?

Sonic Innovation

Did it introduce new textures, rhythms, or techniques?

Lyrical Originality

Does it offer a unique poetic or narrative voice?

Recording Quality

Is the sound well-crafted, balanced, and professionally delivered?

Critical Reception

Was it praised by critics or fellow artists?

Artistic Risk

Does it avoid the easy route? Does it dare to offer something different?

Test of Time

Does it still sound fresh today?

Legacy

Did it influence other artists? Did it leave a trace?

Time Capsule

Does it capture something essential from its era?

Balance

Does it blend popularity with artistic depth?

Diversity

Does it bring linguistic, stylistic, or geographical variety?

The JGC Factor

A unique blend of intuition, experience and sensitivity. It cannot be measured, yet it is instantly recognisable.