1953

From Swing to the Rebel Beat

A Time Capsule in Music Curated by JGC

Looking for a shortcut?

If you prefer to cut to the chase or simply don’t want to lose time, you’ll find the full song selection linked to YouTube and a Spotify player right at the bottom of the page.

A selection based on quality and relevance, not on mass trends.

A Quick Note About This Year's Selection

We're still putting the finishing touches to this year's overview, but we couldn't wait to share some standout tracks that are strong contenders for the final list.

What you'll find here is our working shortlist - songs we've chosen not just because they were popular, but because they truly captured something special about 1953. Some made history, others broke new artistic ground, and a few just perfectly bottled the mood of the times.

Think we've missed an important one? We'd genuinely love to hear from you - just tap the contact button up top to share your suggestions. After all, the best musical conversations are the ones we have together.

The Code of Life and Music: 1953 Unveils the Double Helix

While the two superpowers competed in megatons and measured their might in mushroom clouds, two scientists at the University of Cambridge were unravelling an ancient mystery inside the Cavendish Laboratory. On 25 April 1953, nestled in the pages of Nature, a quiet revolution was born: Watson and Crick unveiled to humankind the spiralled manuscript of life with a modest announcement:

“We wish to suggest a structure for the salt of deoxyribose nucleic acid (D.N.A.). This structure has novel features which are of considerable biological interest.”

That helix, with its base pairs dancing in symmetry, found echoes in the harmonies of the era: musical scales intertwining like nucleotides, songs replicating through covers, variations and new rhythms. While rock and roll was incubating its own revolution in the studios of Memphis, the DNA double helix revealed this: beauty blooms alike in biology and blues when it stays humble, and emerges from the perfect combination of simple elements into something eternal.

Watson and Crick didn’t merely explain how life replicates itself: they ushered in an era of quiet revolutions. Medicine, agriculture, forensic genetics… all were rewritten with this new alphabet. And meanwhile, music—that mirror of the human soul—followed its own path of repetitions and mutations. Of course, to compare the double helix to a song is, perhaps, to mistake the map for the territory.

Yet in 1953, as science decoded the language of inheritance, songs like Crying in the Chapel (The Orioles) and Your Cheatin’ Heart (Hank Williams) reminded us that culture, too, is passed on, not with the accuracy of molecules, perhaps, but with undiminished emotional force.

Two helices, indeed: one written in nitrogenous bases, the other on musical staves. The first, a universal law; the second, a fragile and glorious invention of humankind. And in that pivotal year, as biology found its Rosetta Stone, music was busy weaving the emotional dictionary of a generation, one note at a time.

The American Roots Singer-Songwriter and Rural Reciter

1st January 1953. Hank Williams was found dead in the back of his Cadillac. Just twenty-nine. For the man who'd turned heartache into songs the whole world sang (“Cold, Cold Heart” or Good Lookin'), that final heart attack barely came as a surprise. Not after years of patching up pain with whatever came to hand, all those lonely drives down dark highways, pouring everything he had into songs that left him hollowed out. By then, he’d given so much of himself, there was almost nothing left.

By 1950, something in him had changed. He started singing less like a performer and more like a man getting something off his chest. As Luke the Drifter, he put down fifteen tracks that didn't sound like anything he'd done before. These weren't proper songs, not the sort you'd hear in dancehalls. Just quiet reflections on hard times and the struggle to be better, with nothing but the faintest guitar to keep them company.

"This is who I really am," he once told his producer. He knew they wouldn't sell. But he needed them to exist.

The alias wasn’t a gimmick. It was a shield. Jukebox owners expected barroom music, not sermons about suffering.

So Hank sent Luke in his place. He’d even introduce him on the radio as “a cousin just passing through,” letting the Drifter talk of funerals, hardship, and saving grace. The disguise gave him something he rarely had: permission to be vulnerable in public.

He leaned fully into the character. These weren’t just side projects—they were confessions. “Just me and my guitar,” he once said, “talking about the things we’d seen… the kind of truths you find at 3 AM when the whiskey’s gone but the pain remains.”

Today, those recordings are seen in a different light. Not just as oddities, but as something that quietly changed the rules. Critics like Patrick Huber have traced in them the early shape of American roots songwriting – long before Dylan – or even the cadence of modern spoken word. Luke the Drifter may well have been country music’s first conscious alter ego.

And that's the strange thing about it. In 1950s Nashville, where every note got buffed up for the wireless – all polished vocals and tidy endings – Hank somehow walked both paths at once. The proper star with his name in lights, and this shadow of a bloke just passing through. The jukebox hero… and a faint voice in the corner of the room, saying the things no one else would.

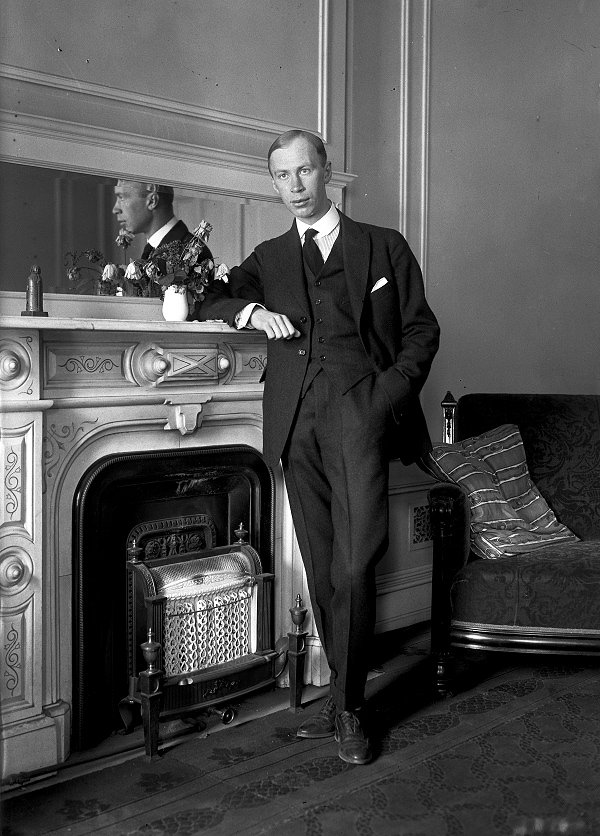

Joseph Stalin and Sergei Prokofiev: 5th March 1953

On that winter's day, Moscow ended the day with two profound absences. Stalin, the leader who had shaped the destiny of the Soviet Union, left a legacy of thirty years of total authority. In opposition, in the shadows of his isolation, Sergei Prokofiev closed his eyes forever.

The former departed amidst artillery salutes and official speeches; the latter, almost in secret, as if the regime preferred to forget it was also losing one of the great composers of the century.

Image from the Manhoff Archive, public domain (U.S. Army).

The Soviet authorities, fearful of overshadowing the “National Mourning”, deliberately delayed announcing Prokofiev's death. No flowers nor headlines: just a small corner in the papers days later, as if he didn't deserve to coincide with the power's grief.

The silence, however, had begun long before his death. In 1936, Prokofiev returned to the USSR, lured by promises of artistic recognition and stability. But applause from the regime came with fine print. Soon, he was compelled to compose patriotic works, most notably Zdravitsa, a cantata celebrating Stalin’s 60th birthday. Beneath this surface compliance, however, his sonatas and symphonies began to speak in darker tones. The Piano Sonata No. 7, written amid bombings and ideological pressure, doesn’t explode — it smoulders.

The irony of fate: Prokofiev, the very man who in 1914 had defeated the invincible Capablanca in one game of a simultaneous display in St Petersburg, couldn't win this final move against history. Two lives that began under the Tsars of Imperial Russia, both deceased in Moscow: one as a symbol of the State, the other, silenced by it. One was mourned by millions; the other, remembered only in hushed tones.

Although an unjust silence closed his cycle, his music has endured, and returns, like bluebells in a forgotten wood: they bloom en masse in spring, carpeting ancient forests, then vanish, only to reappear the next year with quiet precision. It took on new forms, crossed borders, and found its way into school halls and concert stages. One piece, in particular, would go on to outlive the regime that tried to eclipse him.

His music is heard and known by most children all over the world without knowing his name. His celebrated fable, Peter and the Wolf (1936), is a musical fairy tale and so much more. It is a tutorial in storytelling through sound. Each character plays a key role and is voiced by a different instrument in the orchestra. Thus, Peter's little bird friend is a flute that warbles happily. The unlucky duck is the languorous oboe. The cat that treads without leaving footprints is the clarinet. The grandfather always protesting is the respectable bassoon. The grey wolf is represented by three French horns. The timpani and the bass drum symbolise the wolf hunters. Peter walks confidently through the strings, and the wolf? You will sense his presence lurking in the horns’ deep rumble well before you catch sight of him.

It’s a tale woven in music, one that educates while it delights, and remains long after the final note disappears. Stories may end. But music, like childhood, knows no true ending. It pauses, only to begin again.

You don’t just hear this fable. You see it with your ears. The wolf’s horns growl long before he appears. The strings hum with Peter’s quiet courage. It’s a lesson in music that lasts beyond the final note.

Django Reinhardt: The One Who Wakes (Though Not Always on Time)

In 1953, the music world lost more than just famous names. It lost Django Reinhardt — one of the most original guitarists of the century. He died at 43, but left behind a legacy that still sounds fresh, unpredictable, and alive.

People called him Django, a Romani name meaning “I wake up.” It suited him, in its own way. He missed trains and rehearsals, but never missed the mark when it came to music. His real name, Jean Reinhardt, was for officials and border crossings. On stage and in life, he was always Django: brilliant, restless, and utterly himself.

Django arrives late for a concert with the Duke Ellington orchestra at Carnegie Hall in New York City, in November 1946. No sheet music, no rehearsal — just Django, as he was. Some were hoping for a smooth blend with the band. What they got was something else: six curtain calls from a crowd that understood they were hearing a performance no one could imitate.

He died young, like many in 1953. But Django was never about staying long — he was about showing up when it mattered, and leaving a trace that doesn't fade. His clock ran differently. But when he played, time stopped.

"Dooley" Wilson: the everlasting Sam

In 1953, the world of the arts said goodbye to Arthur "Dooley" Wilson, an actor and singer whose legacy began with a curious contradiction.

Born in 1886 in a modest Texas town of fewer than 10,000 people, in a modest Texas town of fewer than 10,000 people, he was the youngest of five siblings, he started singing in church at the age of seven, shortly after his father died, doing whatever he could to earn money.

By 1908, he’d already acquired the nickname that would follow him for the rest of his life: Dooley, born out of a youthful irony. As a Black teenager, he used to paint his face white to impersonate an Irishman singing Mr. Dooley — a contradiction that somehow foreshadowed his cinematic fate.

Yet no aspect of his legacy would be as defining as the second major paradox of his career: Sam, the cherished pianist in Casablanca (1942), a role Wilson portrayed without playing a single note. A talented drummer and experienced singer, he had never picked up the piano. At Rick’s Café, the true pianist, Elliot Carpenter, played the music, while director Michael Curtiz strategically placed the piano to conceal the trick.

Wilson’s job was to move his hands in time, pretending to bring to life the notes of As Time Goes By.

Publicity still by Warner Bros. • Image in the public domain (no copyright notice). Source: Wikimedia Commons

The irony didn’t stop there. His singing, too, was pre-recorded. What audiences saw on screen was Wilson syncing his lips and hands to a playback — before the word even existed. The man who made the world believe in the magic of the phrase “Play it again, Sam” (which, curiously, is never actually said that way in the film) was once again becoming a legend not for what he did, but for what he appeared to do.

Las líneas exactas que Ingrid Bergman (Ilsa) le dirige a “Dooley” (Sam) son parte de un breve pero memorable intercambio:

Ilsa: “Play it once, Sam. For old times’ sake.”

Sam: “I don't know what you mean, Miss Ilsa.”

Ilsa: “Play it, Sam. Play ‘As Time Goes By’.”

Sam: “Oh, I can’t remember it, Miss Ilsa. I’m a little rusty on it.”

Edwin Hubble and Robert Millikan: When Two Stars Faded in 1953

Both scientists passed away in 1953. By then, most people in the scientific world already knew their names. They had done things that changed how others thought about the universe. Still, not everything was as clear as it looked. Some parts of their stories got more attention than others. And some names, equally important, didn’t get mentioned at all. Not everything they were credited for started with them, and not everything others did got noticed when it should have.

Behind the headlines and awards, there were missed citations, untranslated work, and ideas that arrived too early or from the wrong language. Some chapters were highlighted, others forgotten. Their stories are remembered for what they revealed — but also for what was left unsaid.

Hubble had his eyes on the stars, but he also knew how to face the public. An astronomer from Missouri, refined in manner and almost cinematic in appearance, he became the man who “proved” that the universe was expanding. Millikan, on the other hand, needed no telescope to shine. He was a physicist, strategist, and institutional architect. While Hubble explored the limits of the visible sky, Millikan was solidifying the reputation of Caltech in Pasadena, turning it into a beacon of American science. One sought galaxies. The other, legitimacy.

Credit: NASA / ESA / Hubble. Published under CC BY 2.0 license. Original source: Wikimedia Commons.

Both were celebrated, but not without shadows. Hubble’s renowned 1929 paper, which correlated the velocity at which galaxies move apart with their distance, is still taught as a milestone. Back in 1927, Georges Lemaître, a priest from Belgium, had already come to the same conclusion. His maths added up too — no less precise, just less heard. The difference? He wrote in French. His paper didn’t make it across to the English-speaking world, at least not in time. When it was translated in 1931, the key passages on cosmic expansion were simply left out.

What few remember is that, even earlier, in 1922, the Russian mathematician Aleksandr Friedmann had already solved Einstein’s field equations, deriving dynamic solutions that allowed for an expanding or contracting universe. He published from Petrograd, in German, and died three years later, unaware that his calculations had opened a new cosmological era. Today, his name survives in equations alone. The broader narrative went elsewhere.

This is not about blame, but something more telling. In science, as in politics, facts matter — but narrative matters more. It is not enough to discover; one must be heard, cited, translated. Lemaître was no less lucid than Hubble. Friedmann no less rigorous. They simply had less luck with language, location and timing.

Millikan’s case mirrors the same pattern. His oil-drop experiment became a textbook model of precision in measuring the electron’s charge. Yet the Austrian physicist Felix Ehrenhaft had presented similar findings even earlier, and some argue he may have detected sub-electronic charges that Millikan chose to disregard. Ehrenhaft published in German, within a postwar context shaped by nationalism and scepticism, and his results were often seen as inconvenient or too messy to replicate. Millikan, by contrast, offered data that was crisp, clean and reproducible. He himself admitted to having discarded results that didn’t fit his expectations.

Hubble and Millikan had more in common than just dying in the same year. They’re both remembered as much for how their stories were told as for what they actually found. Each shaped their own narrative. And in doing so, they cast long shadows over earlier voices who had said similar things — in other languages, in other contexts.

Image courtesy of the Los Angeles Times Photographic Collection, UCLA Library – Wikimedia Commons.

Perhaps this is the real pattern behind scientific revolutions. Not the solitary ascent of lone geniuses, but something closer to the vision of Imre Lakatos: a contest between research programmes that is determined not only by logical rigour, but by the ability to survive time, translation and forgetfulness. Friedmann’s theory was mathematical. Lemaître’s, physically visionary. Both were eclipsed by an observer with better publicity. Ehrenhaft’s claims were awkward, unpolished, badly timed. Millikan’s, immaculately edited.

The sky, as Hubble once showed, is not static. Legacy isn’t either. Credit drifts. Narratives shift. And in that movement, something closer to truth sometimes begins to emerge — not from who spoke first, but from who managed to be heard.

The Last Breath of Ibn Saud

It is no simple—nor fair—task to condense into a list the names that faded that year. Memory is selective: we remember some, forget others. How does one measure the weight of an absence? We shall not attempt it.

These words are but scattered grains against the tides of oblivion.

Some deaths resonate beyond silence. So did the death of Ibn Saud, the Bedouin who shaped a kingdom with the edge of his insight. A man who could discern in the dunes what others overlooked: the convergence of age-old tribal authority and the black gold flowing beneath the sands.

When Ibn Saud died on 9 November 1953, he left behind more than just a country; he left behind a pact between the Qur'an and oil pipelines, between Hajj rituals and Western interests.

Was he a unifier or a strategist? History still debates. But beneath Riyadh’s sun, his shadow lengthens still.

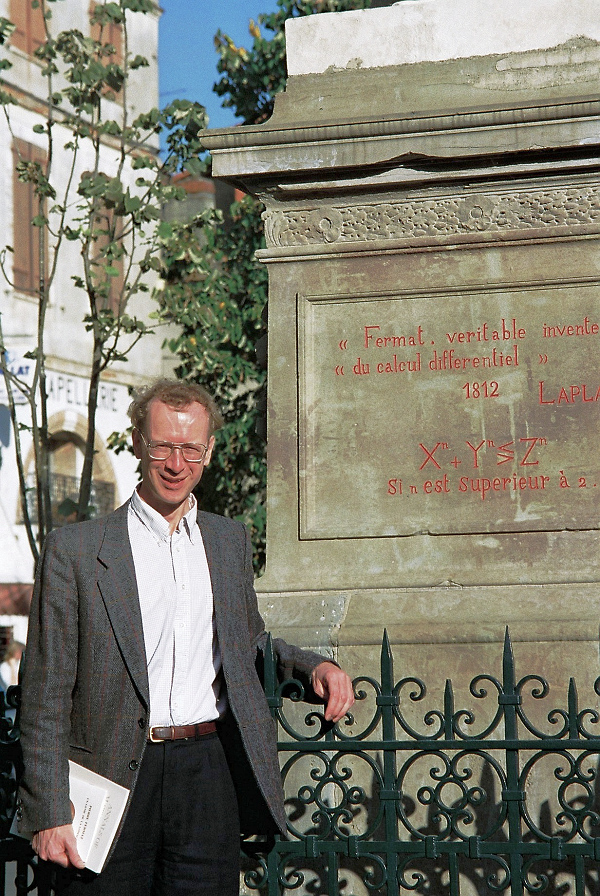

Andrew Wiles and the Proof That Took Centuries

While two scientists in Cambridge were decoding the structure of DNA, as noted in a previous section, a child was born who, decades later, would shed light on one of the most enduring mysteries of human thought. His name: Andrew John Wiles.

His story begins softly, as true dreams often do. As Wiles himself recalled in The Proof documentary:

“I was a ten-year-old, and one day I happened to be looking in my local public library, and I found a book on math and it told a bit about the history of this problem, that someone had resolved this problem 300 years ago, but no one had ever seen the proof. No one knew if there was a proof. And people ever since had looked for the proof. And here was a problem that I, a ten-year-old, could understand” — just imagine! — “that none of the great mathematicians in the past had been able to resolve. And from that moment, of course, I just tried to solve it myself. It was such a challenge, such a beautiful problem.”

That enigma was the so-called Fermat’s Last Theorem.

For others, that childhood desire would have been a passing game, but for him it became the intellectual compass of his life.

Wiles grew into a mathematician, a researcher, and later a teacher. But the question that first caught his imagination as a child stayed with him. One day, he chose to confront it again. For seven years, he worked in complete secrecy. He shared nothing with colleagues or friends — not even with the head of his department. Only his wife knew what he was attempting.

Rather than approach Fermat’s Last Theorem head-on, he followed a different path. He set out to prove the Taniyama–Shimura conjecture, a modern idea which, if true, would bring Fermat’s old claim within reach. The plan was daring. He carried it out entirely on his own.

Years later, when trying to explain what that mathematical journey meant, he resorted to an unforgettable image:

“Perhaps I could best describe my experience of doing mathematics in terms of entering a dark mansion. One goes into the first room, and it's dark, completely dark. One stumbles around bumping into the furniture, and gradually, you learn where each piece of furniture is, and finally, after six months or so, you find the light switch. You turn it on, and suddenly, it's all illuminated. You can see exactly where you were. At the beginning of September, I was sitting here at this desk, when suddenly, totally unexpectedly, I had this incredible revelation. It was the most — the most important moment of my working life.”

That long period of illumination culminated on Wednesday 23 June 1993, when Wiles concluded the last of three lectures in Cambridge and, with quiet resolve, wrote on the blackboard that he had proved Fermat’s Theorem. Then he added, almost gently: ‘I think I’ll stop there.’

That gesture, so humble, so powerful, did more than conclude his lectures. It set off a wave of astonishment across the world. The very next day, 24 June, the news travelled the globe.

That Thursday morning, in the southern hemisphere, an echo of that revelation reached a modest classroom in Montevideo.

A student brought me a clipping from El País. Tucked between articles on politics and economics was the headline: a British mathematician had solved Fermat’s enigma. That changed everything. I set aside the lesson plan and spent the class talking about it — about how extraordinary it was. I wanted the students to feel what I was feeling. It wasn’t every day that a three-century-old mystery came to an end.

But the story was not yet over.

Several weeks later, an error was discovered in the proof. It was no minor detail: a structural flaw that threatened to bring down the entire logical edifice. The error was uncovered between August and September 1993, while the proof was undergoing review for publication in the Annals of Mathematics. It was mathematician Nick Katz who, examining the manuscript line by line, detected the crack in a sensitive part of the proof.

Wiles tried to fix the error on his own, but couldn’t. So he did something deeply human. He reached out for help.

He picked up the phone and called his former student, Richard Taylor. Over the following months, they went back through the proof step by step, checking every argument and revisiting each part with fresh eyes. It was in that quiet and careful process — the willingness to return to familiar ground — that the breakthrough finally came. It didn’t arrive with noise or celebration. They didn’t stumble on the answer in a flash. It came bit by bit, as they went over the work again and again. Nothing dramatic — just a subtle shift, a realisation growing slowly until, one day, they could see it clearly. The missing part had been there all along. They just hadn’t noticed it.

That error — and the decision to share his work — does not diminish his achievement. On the contrary: it ennobles it. It reminds us that even at the highest summits of intellect, error is not failure but part of the process. That even the brightest minds stumble. And that true merit lies not in being infallible, but in not surrendering when the flaw is found.

Wiles wasn’t chasing fame. What he loved was the private moment when the puzzle was finally solved: no applause, just quiet certainty. No grand speeches. None were needed. His strength lay in his approach to work: no shortcuts, just a steady mind that could find beauty where no one else had thought to look.

From the South, Where Music Breathes

To close this colorful introduction, and since these music lists are woven from this corner of the Río de la Plata, we allow ourselves a brief tribute to an illustrious son born precisely in 1953: Jaime Roos. Singer, musician, composer, and sound alchemist, a name now essential to the history of Uruguayan music. His music, born in Montevideo, flowed across genres as naturally as breathing in a city, effortless and vital.

Impossible to pigeonhole, his genius fused candombe, murga, rock, tango, and milonga into a melting pot where each essence retained its truth.

A final memory: Hong Kong, 1996. Tower Records. His chords finding their way to foreign shelves, unexpected yet perfectly at home. And there, mapless and compass-free, the sight of one of his unmistakable album covers told us we were home. That won't be the last time we mention that temple of the vinyl record; we still hold a few stories like hidden bottles of wine, waiting for the right moment to be uncorked.

His greatness lies there: in elevating the human without pretence, in weaving verses that pulse with truth, far from the beaten track. Roos transformed streets into songs, and those songs into a homeland small enough to carry in your pocket.

Essential Melodies, Curated by JGC

Musical Filter

Some of the criteria that helped decide which songs deserved a spotlight—and which were left behind:

Cultural Impact

How did it resonate in its time? Did it leave a mark on culture?

Sonic Innovation

Did it introduce new textures, rhythms, or techniques?

Lyrical Originality

Does it offer a unique poetic or narrative voice?

Recording Quality

Is the sound well-crafted, balanced, and professionally delivered?

Critical Reception

Was it praised by critics or fellow artists?

Artistic Risk

Does it avoid the easy route? Does it dare to offer something different?

Test of Time

Does it still sound fresh today?

Legacy

Did it influence other artists? Did it leave a trace?

Time Capsule

Does it capture something essential from its era?

Balance

Does it blend popularity with artistic depth?

Diversity

Does it bring linguistic, stylistic, or geographical variety?

The JGC Factor

A unique blend of intuition, experience and sensitivity. It cannot be measured, yet it is instantly recognisable.