1950

The first heartbeats of a new era

A Time Capsule in Music Curated by JGC

Looking for a shortcut?

If you prefer to cut to the chase or simply don’t want to lose time, you’ll find the full song selection linked to YouTube and a Spotify player right at the bottom of the page.

A selection based on quality and relevance, not on mass trends.

1. Introduction

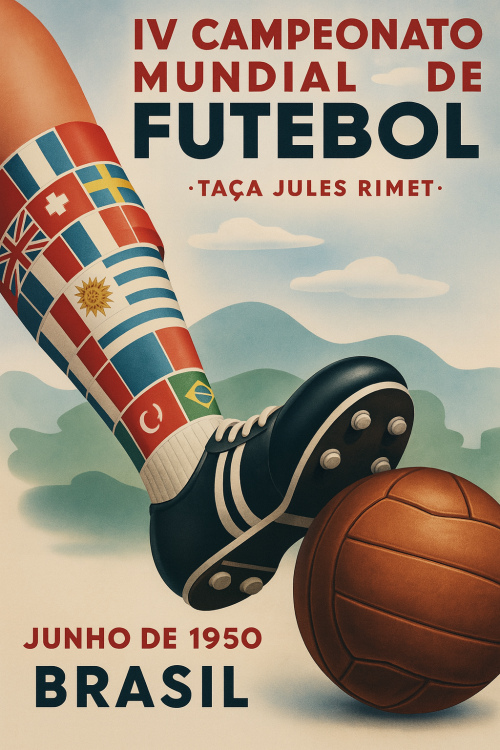

When people talk about big moments in 20th-century music, 1950 usually isn’t the first year that comes to mind. This year has been one of those that pass by without much notice or memory. Nothing transcendent seems to have happened. In fact, if someone who knows about music is asked what the best song of 1950 is, the questioner is likely to breathe a deep silence. However, if one stops to think for a moment more deeply and approaches it with a more powerful magnifying glass, one may begin to realise that things are starting to move. It is not only the arithmetical significance of the 50th that justifies that we started our selection precisely at that historic moment. Nor is it a tribute to Uruguay for having beaten Brazil at Maracanã in the famous World Cup, no, it is simply the beginning of a decade hinge that will change music forever.

This little reflection isn’t trying to be an in-depth study. We’re not diving into technical details or obscure facts. What we want is to share a clear, down-to-earth take on a year that, while not explosive, was still part of the bigger story. If you’re curious about how music changes with the world around it, and how small shifts can matter more than they seem; this is for you.

A lot of people see the early 1950s as a calm stretch before the musical storms of the mid-decade. That’s fair. But from where we stand, 1950 already had signs of change. It was a year of transitions, not headlines; and that makes it worth remembering.

2. Rebuilding After the War

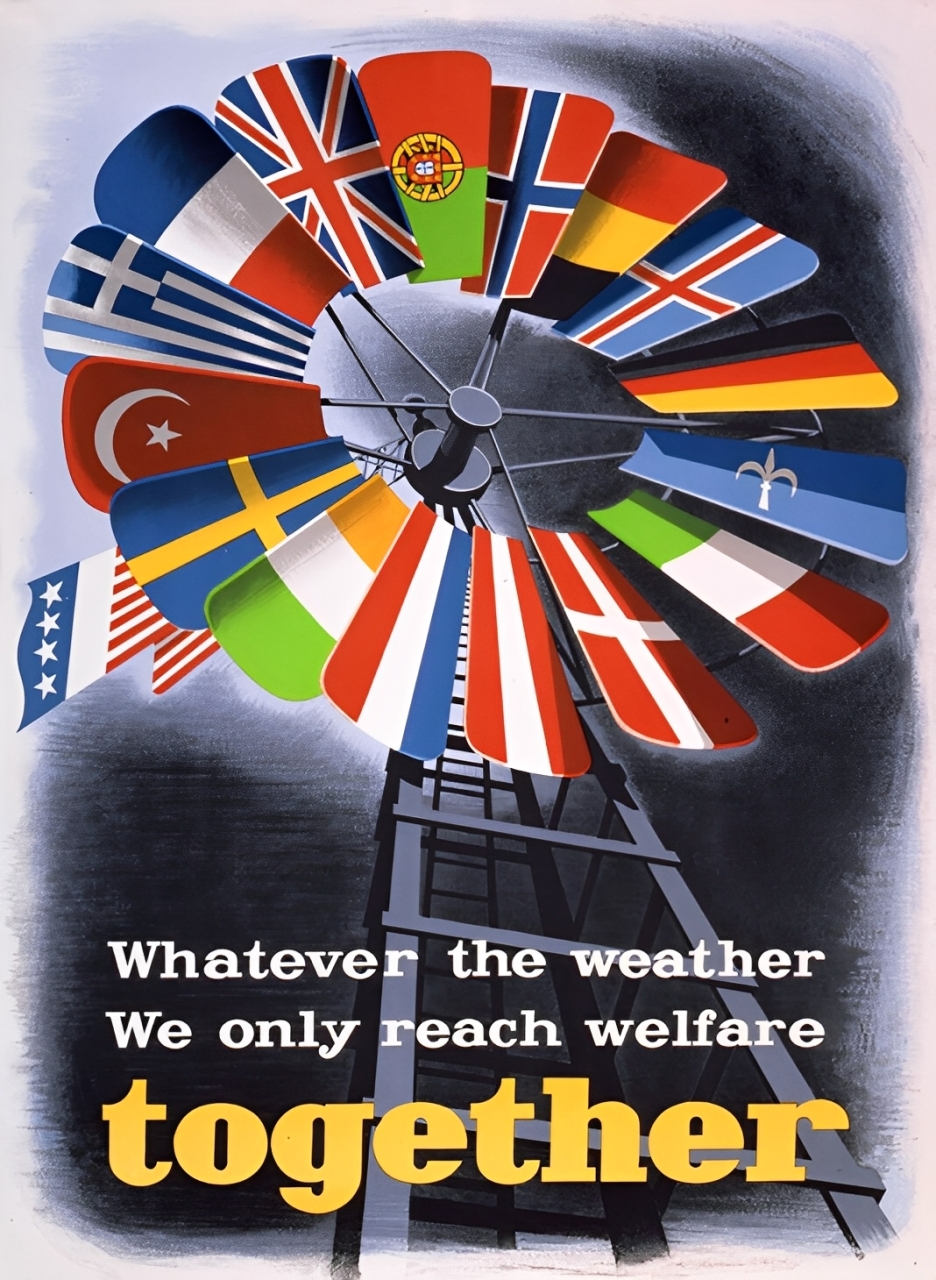

By the start of the decade, five years had passed since World War II ended. Even so, its effects were still everywhere. Cities in Europe and Japan were rebuilding brick by brick, and life was only just getting back to something that felt like normal. Culture, of course, took time to return; and music was no exception.

Let’s be honest: people had more pressing concerns. Food, shelter, clean water; those came first. Music wasn’t at the top of the list. A lot of concert halls and recording spaces had been damaged or used for the war. Equipment was outdated or hard to replace. And funds? Mostly directed to basic needs.

In Western Europe, the Marshall Plan brought some relief. With outside help, factories reopened, jobs returned, and certain sectors began to breathe again. But when it came to music, things moved slowly. Most records stayed local, and the idea of songs crossing borders just wasn’t part of the reality yet.

3. Technological Limits and a Narrow Editing Landscape

Back in 1950, most music was still being put onto 78 RPM shellac records. They were delicate, easy to break, and didn’t hold much; just a few minutes of sound on each side, and the audio quality wasn’t great either.

Magnetic tape had been around since the 1930s — it was a German invention — and people in the industry knew about it. But at that point, it hadn’t really taken off as the go-to method for recording music. Major labels like Columbia, RCA Victor, and Decca ran the show, but recording sessions were expensive and mostly took place in the U.S., the U.K., or a few other industrialised countries.

Columbia had introduced the 33⅓ RPM long-playing record, the LP, in 1948, but it would still be a few more years before it really took off.

4. Claude Shannon: When Sound Met Code

That same year, a quiet revolution began to reshape how we listen to the world. Claude Shannon published the second half of A Mathematical Theory of Communication, a work that didn’t just speak to engineers. It reached into the very essence of what sound, language, and music truly are. From that moment, melodies were no longer merely emotions carried by rhythm. They became signals, patterns, bits. A new way of hearing the world was taking shape—the digital kind.

Image licensed under CC BY 2.0.

As if that weren’t enough, Shannon also wrote another landmark paper that year: Programming a Computer for Playing Chess. It was not just about chess — it hinted at something bigger. If a machine could play, perhaps it could also reason, learn, decide. Artificial intelligence, still unnamed, was taking its first steps. While musicians were improvising new harmonies, machines were beginning to explore their own.

5. Early Days of Broadcasting and Music

Radio remained the main channel for sharing music, although in several countries more importance was given to local or international news, soap operas or sports information. Music programming varied greatly from country to country and, in many places, local stations broadcast only local or traditional music.

Television, on the other hand, was still a novelty. In the United States, only around 10% of households had a set in 1950, and in most of the world, TV broadcasting had yet to take root, or even begin.

Unlike in later decades, neither radio nor television had yet become a true launching pad for international hit singles. Programmes dedicated to new talent or recent musical releases were rare and often limited to local audiences. The idea of discovering music through televised performances still belonged to the future.

6. Music That Stayed Close to Home

In 1950, the music scene in the United States depended on where you were. In the big cities, for example, jazz was played late into the night. In other localities, blues was played at small gatherings, while country music was played in rural places through radios. And somewhere in between, a new name began to appear: rhythm and blues.

These sounds had been around for a while, each with its own crowd. But every now and then, in a bar, a dance hall, maybe even on someone’s back porch, they began to mingle. You could catch it in the way musicians borrowed riffs, or how certain beats crossed into unexpected songs. It didn’t have a name yet, but something new was taking shape.

People would later call it rock and roll. At that point, no one really knew where things were heading — they just felt the ground starting to shift. The borders between styles weren’t so fixed anymore, and little by little, the rules were being rewritten.

In Latin America, the music scene was full of emotion. Boleros were popular, and tango still held a strong presence. People danced to rancheras and tropical rhythms that would eventually evolve into genres like salsa and bossa nova — though no one was calling them that just yet.

Europe was moving to its own beat. In France, chanson was everywhere; often poetic, sometimes tinged with melancholy. In Portugal, people turned to fado, with its slow melodies and quiet intensity. Across much of the continent, folk traditions still held sway. Songs were passed down in families, sung in local languages, and closely woven into daily life.

There wasn’t much of a global music network. Songs rarely crossed borders, not because they lacked quality, but because there simply weren’t strong systems in place to carry them. Translation, licensing, and promotion tools did exist, but they didn’t reach very far.

7. Few World Superstars, and Few Stars at All

Back in 1950, the idea of a global pop star just wasn’t part of the picture. Elvis hadn’t arrived yet, the Beatles were still in school, and Michael Jackson hadn’t even been born. Most artists who found success success at the time stuck to what people already liked. They weren’t trying to shake things up — they just knew how to make a tune that stayed with you, how to say something that felt real, and how to put on a show people wouldn’t forget.

Frank Sinatra, Édith Piaf, Nat King Cole… they were household names for good reason. Their songs travelled far, even if the world wasn’t quite ready yet for truly global fame.

But even artists of that calibre didn’t reach every corner of the world the way future stars would. The kind of success that crosses borders and languages was still something people hadn’t quite imagined.

The music industry had not yet turned its attention to young people. In 1950, there were simply children and adults; the word teenager was rarely used in everyday conversation. The concept of a youth market hadn’t yet emerged, although from the mid-1950s onwards, it would go on to transform the music business entirely.

8. Music and Film, Just Before the Big Shift

In the years leading up to 1950, films had already gifted audiences with a few unforgettable songs. Judy Garland’s “Over the Rainbow” from The Wizard of Oz stayed in many hearts. Casablanca brought “As Time Goes By”, a tune that still lingers today.

Fred Astaire turned “Cheek to Cheek” into a classic, and Bing Crosby’s “White Christmas” became a seasonal anthem, selling more copies than anyone could have imagined.

But these were exceptions, not the norm. In most cases, music and film hadn’t yet joined forces in a way that truly shaped popular culture — at least not yet.

The golden age of Hollywood musicals hadn’t quite begun. Singin’ in the Rain, The Band Wagon, West Side Story — those iconic titles were still waiting in the wings. That wave was slowly building, but it hadn’t broken yet.

At the time, most film soundtracks were orchestral, and you’d usually only hear them at the cinema. Still, many of us know how powerful a good score can be — a swell of strings to lift a moment, a soft piano line to pull at the heart, a few notes to hold the air still before something important happens. Studios often relied on talented composers who weren’t household names, but who knew exactly how to shape the audience’s emotions — often without saying a word.

Even so, that music rarely made it beyond the cinema. You wouldn’t hear it on the radio, and most people didn’t think of buying it on a record. Soundtracks weren’t yet something you brought into the home. They stayed where they began — part of the film experience, not part of daily life.

9. Uneven Development of the Recording Industry Worldwide

Some countries (such as Argentina, Mexico, Brazil and France) had relatively active recording industries, yet they remained isolated in terms of distribution.

Take Argentina. Even fifteen years after his death, Carlos Gardel’s voice was still everywhere. That’s how long a legend could linger at the heart of a nation’s culture.

Brazil had Carmen Miranda, a global star thanks to Hollywood. But back home, opinions were divided. Some celebrated her success; others felt that her sequinned version of Brazil didn’t quite match reality.

In much of Africa, music lived where it always had, in villages, at festivals, woven into daily life. Commercial recordings would come later, often shaped by foreign labels under colonial influence.

Behind the Iron Curtain, music faced tighter controls. If a song didn’t follow the party line, getting it pressed to vinyl was an uphill struggle. Under Stalin, creativity was kept on a short leash.

Meanwhile, over in Asia and the Pacific, music simply followed its own path. Japan’s film soundtracks pulsed with energy, India’s ragas spiralled into the heat of the afternoon, and islanders kept ancient rhythms alive, beautiful sounds that rarely travelled beyond their own shores. Not because they lacked brilliance, but because the world’s musical highways hadn’t reached them yet.

10. Some Notable Songs of 1950: Rare but Memorable

Although most songs recorded in 1950 stayed within their own borders, a few titles managed to travel further, sometimes right away, sometimes years later.

One example is “The Tennessee Waltz”, performed by Patti Page. It became one of the first popular songs in the U.S. to reach listeners from different social backgrounds.

Another is “Mona Lisa”, a soft ballad by Nat King Cole. Some songs just grew into classics without anyone noticing. That polished orchestra sound people loved back then? Plenty of tunes slipped right into that groove.

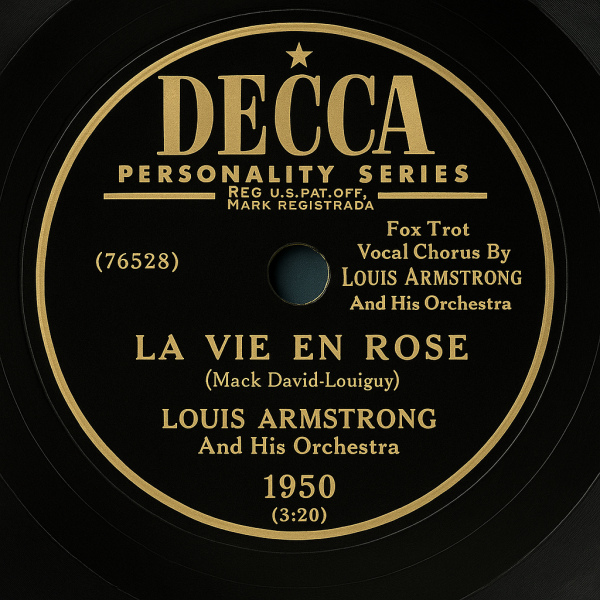

Take Édith Piaf's “La Vie en Rose”, recorded in the '40s, but really caught fire worldwide as the '50s rolled on. Same happened with “Bésame Mucho”. Mexican composer Consuelito Velázquez wrote it back in the 1930s, but the '50s turned it into a global favourite with cover after cover.

Then there's Brazil's “Tico-Tico”, that zesty little number written in 1917. Would’ve stayed local if not for Carmen Miranda’s fruit hats and Xavier Cugat’s orchestra giving it the full Hollywood treatment during the postwar years.

But these were, in truth, exceptions. Most of the music produced in 1950 remained local, fleeting, or modest in scope, shaped more by circumstance than by the search for global fame.

11. A Bird's-Eye View of What Was to Come

The musical world of 1950 may have seemed modest on the surface, but change was already latent, constantly and irreversibly evolving.

In 1951, Gibson introduced the Les Paul, the first solidbody electric guitar. It didn't cause much of a stir at first, but it laid the foundation for the sound of modern music.

Just a year later, the LP—short for Long Play—started to catch on. It delivered better sound and longer playing time, letting listeners enjoy a full album without flipping records. For many, it was the first time music became something to really sit with, not just sample.

In 1953, Ray Charles began experimenting with gospel and rhythm & blues. What emerged was raw, powerful and deeply moving; arguably the first manifestations of what we now call soul.

The very next year, everything changed when Bill Haley blasted “Rock Around the Clock” through every radio in America. That wasn't just music. It was a thunderclap announcing a revolution was coming.

By 1955, two seismic shifts hit at once: Elvis Presley signed with RCA while Chuck Berry dropped “Maybellene”. These guys didn't just sing songs - they rewrote the rules with every sneer and guitar lick. Almost overnight, popular music found itself heading somewhere entirely new.

Then 1956 happened, and rock and roll blew the doors off. Overnight, teenagers weren’t just killing time until adulthood, they were a movement with their own soundtrack. The music industry finally clocked it: this wasn’t just music to hear, it was music to live by. And just like that, the game changed.

12. Final Remarks

1950 was, in essence, a year of slow gestation. The forces that would redefine the global music industry — technological, commercial, demographic, and stylistic — were still assembling. The post-war world was rebuilding not just its cities and economies, but also its cultural networks and infrastructures.

In the absence of mass media saturation or globalised charts, music was still an intimate, regional affair — a fact that, in retrospect, adds a certain charm to the era. While the songs of 1950 may be few and far between on today’s playlists, they belong to a transitional chapter that made possible all that followed.

Essential Melodies, Curated by JGC

Musical Filter

Some of the criteria that helped decide which songs deserved a spotlight—and which were left behind:

Cultural Impact

How did it resonate in its time? Did it leave a mark on culture?

Sonic Innovation

Did it introduce new textures, rhythms, or techniques?

Lyrical Originality

Does it offer a unique poetic or narrative voice?

Recording Quality

Is the sound well-crafted, balanced, and professionally delivered?

Critical Reception

Was it praised by critics or fellow artists?

Artistic Risk

Does it avoid the easy route? Does it dare to offer something different?

Test of Time

Does it still sound fresh today?

Legacy

Did it influence other artists? Did it leave a trace?

Time Capsule

Does it capture something essential from its era?

Balance

Does it blend popularity with artistic depth?

Diversity

Does it bring linguistic, stylistic, or geographical variety?

The JGC Factor

A unique blend of intuition, experience and sensitivity. It cannot be measured, yet it is instantly recognisable.